Find what you need to fuel your work

Deep in the pandemic, visual artist Mark Bradford began work on an epic series called “The Unicorn Tapestries.” It’s inspired by the iconic medieval work of the same name, but created with everyday materials that speak to Mark’s experience: comic book papers, caulk, and other materials from the hardware store, layered and glued and then scratched and etched away to create a tapestry like no other. As he shares each stage of his process in his own words, Mark also shares a mindset that every creative person can apply to their own work: Find what you need to fuel your creativity.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Go find the milk

- Chapter 2: The first tapestry I ever saw

- Chapter 3: Something is killing us

- Chapter 4: In search of beauty

- Chapter 5: I go to art school

- Chapter 6: What I need every day

- Chapter 7: From the darkness of 2020, a spark

- Chapter 8: What the original unicorn tapestries look like

- Chapter 9: How I made the unicorn tapestries

- Chapter 10: Finishing the tapestries

- Chapter 11: You are an artist

Transcript:

Find what you need to fuel your work

Artist Mark Bradford stands with his work “Bones and Their Makers,” 2021. Mixed media on canvas. 2 parts, each part measuring 244 x 183 x 5 cm / 96 1/8 x 72 x 2 in Photo: Brandon Hicks. Image © Mark Bradford Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Chapter 1: Go find the milk

MARK BRADFORD: When I started becoming an artist, I was making a lot of forts on sand. And they would just constantly keep falling over, until I realized that I had to really get the structure and the architecture to build the foundation and build from that.

Organize, Mark. Structure, structure.

I struggle with that. I’m real good with ‘go with the flow,’ swinging from a chandelier in a gold lamé jumpsuit. I was, like, made for that. Not a problem. But I’ve always had to work for structure.

I always think you’re born with half of the equation. You’re born with the structure, and not the fluidity. Or you’re born with too much fluidity and not the structure. So you’re born with one, and you have to work for the other one. If you have the cereal, you better just go find the milk. I can’t tell you where the milk is. I don’t know what store you’re going to have to — I don’t know if it’s Whole Foods. I don’t know if it’s Ralph’s, Food 4 Less. You just got to go find the milk. And nobody can tell you how to find it. That is your journey.

JUNE COHEN: That’s visual artist Mark Bradford. And he’s about to tell us the story of creating “The Unicorn Tapestries,” a series of larger-than-life mixed-media canvases inspired by the medieval tapestries of the same name.

It’s a specific story about reimagining art from another era to respond to the unrest and unease of 2020. But it’s also a universal story about finding what you uniquely need to fuel your creativity. “Go find the milk,” as Mark puts it.

As Mark takes us on the journey of creating “The Unicorn Tapestries,” you’ll hear how he finds exactly what he needs to fuel his work. And what he needs evolves as he does. In his 20s — when AIDS devastates the gay community — he takes a spontaneous trip to Paris to experience beauty, and stays for the better part of 8 years. Then he enrolls in art school — something he never thought he’d do. Later on, what he needs is everything from staying grounded in his working-class values to designing a routine that keeps him working every day.

Here’s what you need to know about Mark and “The Unicorn Tapestries.” Mark is one of the most renowned visual artists working today. His work is held by major museums, including the Met in New York, LACMA in LA, the Hirshhorn in DC. And he’s regularly exhibited at global shows like the Venice Biennale and Art Basel.

As for the “The Unicorn Tapestries,” they aren’t really tapestries. And they aren’t exactly paintings either. To create them, Mark uses a unique process he’s developed over a lifetime of making art. He starts with a canvas of monumental scale, carrying the visuals from the original medieval tapestry. Then he layers the canvas with things like newspapers, magazines, billboard fragments, and flyers. These layers of material are interspersed with things you might find in a hardware store, like rope, caulk, and glue. Then, he scratches, peels, and blasts away at the surface — using solvents, acid, or high-pressure water — and lets different layers emerge for the final tapestry.

When we recorded this interview, “The Unicorn Tapestries” hadn’t yet been seen by the public. Since then, the work premiered at the Serralves Museum in Porto, Portugal.

I’m your host June Cohen, and on this episode, you’ll hear original music composed for piano and flute. For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com.

[THEME MUSIC]

Installation view, ‘Mark Bradford. Àgora,’ Serralves Foundation, Porto, Portugal, 2021. © Mark Bradford. Courtesy Serralves Foundation. Photo: Filipe Braga

Chapter 2: The first tapestry I ever saw

MARK BRADFORD: My grandmother used to put up a tapestry of Martin Luther King at his birthday every year in the house. She would put up Martin Luther King, and she put up JFK. And every year she would tell us exactly who these people were. And so we, as kids, would have to sit there. And I do remember, I was so young, but one of them must’ve been assassinated. There was silence in the house that day.

I say my grandmother, but she wasn’t my grandmother. Me, and my mom, just rented a room from her. It was like a daycare-slash-boarding house, one of those big old Victorian houses. On the ceilings, there were these amazing murals. I used to sit down there and look up at the stained glass. I always felt like I was in a church. These were the religious rooms. The kitchen, that would be the heart. Mama would be in there cooking for everybody.

Mama was a seamstress, and she had the sewing room and inside of it was just yarn and fabrics. All the girls in the house, I would comb and style all their hair. And sometimes we would dress up, and we’d have these promenades on the second floor. We would walk down those long steps with the stained glass in back of us and just be super fabulous, like Scarlett O’Hara, Gone With the Wind, taking the drapes and putting them on your shoulders like Carol Burnett did. And then we would walk down the steps, and it was a very religious experience. I always kind of thought I was like the Pope.

People always ask me, “Well, didn’t you know when you’re in fifth grade that you were creative?” No, I didn’t know. I didn’t have a word for it. I came from a working-class family. My mom was a hairdresser. I didn’t have any middle-class architecture around me to tell — no, please. No. I didn’t grow up like that. Being creative was just part of the DNA of who I was. Thought it was just Mark being Mark.

Chapter 3: Something is killing us

How can you create when you think there’s no future? Find what you need to break the holding pattern.

MARK BRADFORD: I started working in my mom’s hair salon when I was 14, 15. It was in South Central. It was called Foxy Coiffure.

I heard about it early, when it was called GRID. Prince LaBelle came into the hair salon, and he was on a cane, and he had a Jheri curl, which was fabulous in 1979, by the way. No judge, it was fabulous. I had a Jheri curl too. And I used to give him his Jheri curl, and he kept getting thinner and thinner and thinner. And one day I hadn’t seen him for six months. He came into the hair salon. He was about a hundred pounds. He said, “I’m on a cane. And I’m going from hair salon to hair salon and telling black gay men there is something killing us.”

I was a nightclub boy. I had found my calling. Donna Summer said, “Last Dance.” And I was like, “Oh no, wait a minute, girl. Wait a minute. Let me get a couple more before the party ends. Clubs, honey. No school, nightclubs.” That demographic got really hit by HIV. And I buried 75%, 80% of the people that I knew. And I wasn’t 20. I was depressed and scared. And when you have your president at the time not even wanting to mention the name, you felt very isolated and just alone. The church and everything, and God’s retribution and guilt and shame. I was one of those people, right? I was so haunted by HIV and death around me of my peer group, I could not process what life was going to be with so much death.

I was in a holding pattern. Just a holding pattern. Just let me get through it.

I assumed I was going to die, but I thought, what can I do? I just wanted to go and have a look at the Eiffel Tower, just to stare at it, just to see something beautiful.

Mithra, 2008, Los Angeles State Historic Park, LA, 2022. © Mark Bradford. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo- Joshua White/JWPictures

Chapter 4: In search of beauty

How do you find what you need to create? Stay authentic to who you are — and look for what moves you.

MARK BRADFORD: I wasn’t trying to put on my art hat because I was in Paris. I refused to do that. I wasn’t going to get out my sketch pad. I wanted my experience to be authentic to whatever I was feeling. So most of the time I would stay up all night, going to nightclubs. And then I would wake up and leave the youth hostel and then go sleep in the park and buy some bread and some cheese or whatever was cheap from the shop and meet all the other people laying in the parks, half hung over.

People said, “Oh, we’re on our way to Pamplona.” I said, “What’s Pamplona?” “Oh, the running of the bulls.” I said, “What’s running of the bulls?” Well, I went to the running of the bulls. I was like, “Are you kidding me? The outfit is cute, but I’m a six-foot-eight black man. And there’s no way I’m running with the bulls.”

I worked odd jobs. I picked fruit, just whatever. And then when I run out of, run, run out of money, I’d come back to the U.S., and I would work in the hair salon a little bit more. And I really just did that for about eight years. More information about AIDS came out, and then we started to understand what safe sex was. The doctors started talking about medication. Slowly, I began to think I was going to live. And once I began to think that I was going to live, then I started to think about art.

Chapter 5: I go to art school

How do you find confidence as an artist? Connect the dots of your life, and then be who you are.

MARK BRADFORD: My mom didn’t go to university. I don’t know him, but my father did. So going to college just wasn’t part of our conversation. I certainly would not have gone to art school at 18 if you gave me the opportunity. I’m like, “Art school, no; you become an engineer or a lawyer or something to make you money.” And then I would talk to my aunts, and they’d say, “Oh, you remember your uncle. He would always draw all the time.” It’s in my line of Bradfords, but we were just working-class people.

I formalized it when I started going to art school. I was 28. I went to CalArts, which was a very intellectual school. And I went in there with a bad attitude, probably smoking a cigarette and chewing gum. Artists would come and give talks, and they were so brilliant; everything was so intellectual. And at the end, “Are there any questions?” And I was like, “Nope, nope, nope, nope, nope, nope.” I don’t want to sound like I’m not intelligent.

I just had to tell myself, “Well, Mark, either you’re smart or not. And maybe just go for it. Just be who you are and see if it works out.” I had to do the papers, and I had to show up at 8:30, and there was a structure. I was like, “Wow, this is different. People do this all the time? Jesus.” And I fell into it. I wasn’t ever in the back of the class. I was in the front of the class, and I liked what they were saying for the first time since fifth grade. I just could not believe that I would be paying attention. Lo and behold, I finally passed a class.

And then I started to connect the dots of my life, saying, “Well, wait a minute. I think that impulse I had when I was in… Oh, wait a minute. And the costumes that I would sew…” I would start to read about other artists, Black people living on their own terms and James Baldwin and Jack Whitten. And oh my God. I was like, “What? I think I’m kind of like this.”

Chapter 6: What I need every day

How do you build a routine that fuels your creativity? Don’t take yourself seriously, but take your work very seriously.

MARK BRADFORD: It’s very hard to convince me not to work. I’m, like, a worker. I don’t wait to be in a good mood or wait to be operating at a 10 or wait to be inspired. I don’t wait for any of that.

I get up in the morning, get in my car, 15 minutes I drive, I turn on the lights, and I start to work. My studio, it’s one of those old bow truss buildings. If you look up at the ceiling, it’s really textural. And I really like it. Sometimes I lay on the ground and just look up at it. It has a lot of paint peeling off, and it has all these crossing beams and these big struts holding it together. Big old metal skylights. Dropped down a little bit more and I have soft LED track lights. And I turn on all the studio lights. I don’t like it to be dark anywhere, so I turn on everything. I built little studios within the studio. I’ll work on pottery here. I’ll work on a tapestry here. I’ll work on a merchant poster here. Everybody wears white clothes. I get them all from Home Depot, painter’s clothes, Dickies and white shirts, just because I find that it’s easier to fall into the landscape. People just assume I’m a house painter.

Let’s not romanticize what we do. Stop acting like an artist. Don’t take yourself seriously, but take your work very seriously. Let’s not make it always tortured or always virtuous. And I just kind of wish more people wouldn’t romanticize the narrative because then you feel super insecure. It’s the practice of being an artist, like the practice of medicine or the practice of being. It’s a practice.

I just work. And sometimes it literally feels like I’m just taking paper and putting it on a canvas, and it feels like wallpaper. I feel like I could be a wallpaper expert at Home Depot. “Hi, welcome to Home Depot. I’m Mark. I’ll help you put wallpaper on your house.” And then other days, I feel like the material is activated, and I’m activated, and it’s a relationship, and we’re making new ground. And this is amazing. It doesn’t matter; I still show up.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how Mark describes his routine as a “practice.” For him, it’s not romantic, it’s the practical things he needs to keep creating — the white clothes, the light, the space, the daily routine. It’s the structure he needs to fuel his creativity.

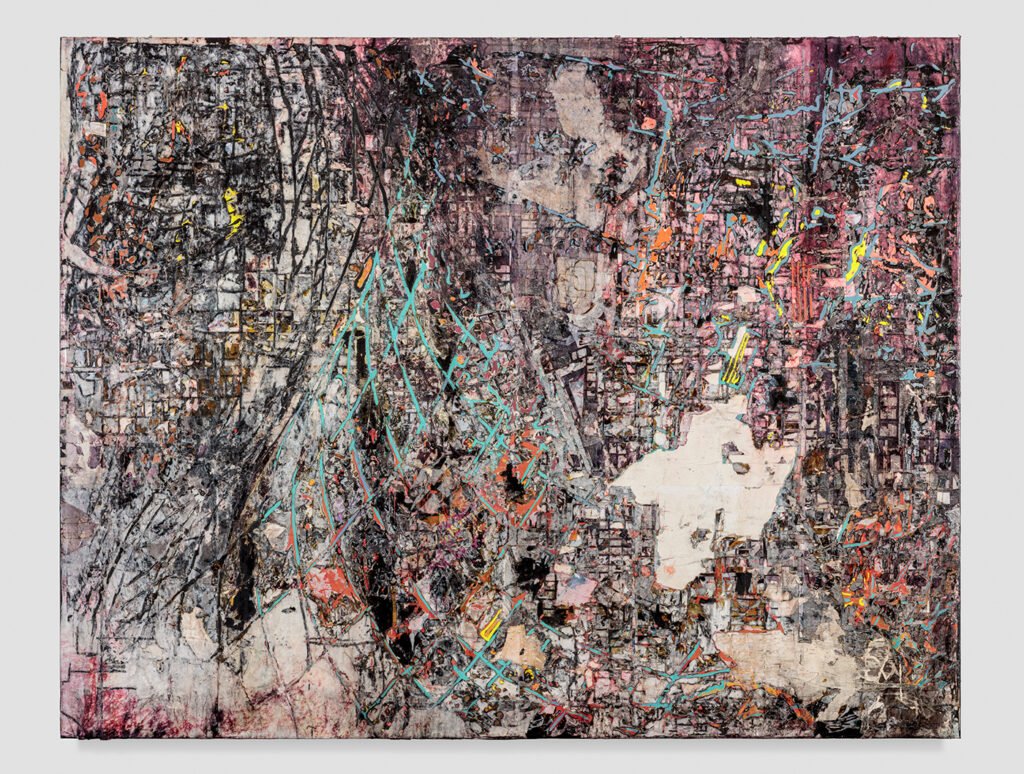

A detail of “The Unicorn Purifies Water,” 2020, showing the technique Mark uses to build his work. Mixed media on canvas 365.8 x 401.3 cm : 144 x 158 in. © Mark Bradford. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures

Chapter 7: From the darkness of 2020, a spark

In a moment of crisis, how do you find your way forward? Resurrect the past.

MARK BRADFORD: Free thought was under duress. That’s what I felt like in 2020. Challenged, and a lot of negative, negative, negative energy was released into the environment. Let me tell you: we had never experienced life through Zoom before, walking around with masks, and not seeing our loved ones, and xenophobia and nationalism rising to hysterical heights. And I mean, you put George Floyd, and you put the pandemic, and you put the reckonings, and you put all that together, I felt very caged; my anger, my confusion, my frustration. And in some ways it was triggering. In the 80s, they kept talking about death and how many people … and the counting, the counting, the counting. And the pandemic, the counting, the counting of death, the counting, always the counting, the counting, the counting.

And for a moment there, it felt like we were in the dark ages and losing things.

But then I believe in resurrection. We have to have some belief that something will resurrect out of all this. And that things will be put together in a different way.

I wanted to look at something historical and then put my modern angst into it. The Dark Ages point back to another moment when so much was lost. The loss of intellectual ideas and collapses of economies and the decline of culture and the decline economically of Europe and just this collapse. The Dark Ages.

The unicorn tapestries are some of the most famous tapestries. Something I could really put myself into and kind of work out this modern-day feeling of loss.

Hinting at its medieval inspiration: “The Unicorn Rests in a Garden,” 2020. Mixed media on canvas 365.8 x 279.4 cm : 144 x 110 in. © Mark Bradford. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures

Chapter 8: What the original unicorn tapestries look like

MARK BRADFORD: They were grandiose. They were big. They were huge. And I liked the relationship to your body. You felt small in comparison to these big tapestries, and they told these big archetypal stories about good and evil. They were like old-school comic books. Big stories, big dramas.

It’s a white unicorn sitting in a wooden enclosure. It looks like this magical garden of flora and fauna. There are so many types of representations. It’s like over a hundred species of plants.

The unicorns were thought to represent Christ. If you really look at the cycle of the unicorn tapestries, it was a complete circle — the birth, the death, and the resurrection of Christ.

They’re hunting him. He’s trapped. I mean, they’re after this guy. And he’s going to be murdered.

Chapter 9: How I made the unicorn tapestries

How do you find the right ingredients for your work? Learn from every failure.

MARK BRADFORD: I actually have been trying to do tapestries for about 10 years. And I’ve just been failing. I just didn’t have the right ingredients. I fail about 50% of the time, unfortunately. The amount of stuff I throw out is just unbelievable. I mean, it’s just ridiculous.

And as I moved through doing other tapestries, I got more bold, but I was so afraid that it was all going to just not work again.

I never felt that I had the right building blocks before, but I felt like I did have it now.

I knew what my process was going to be on tapestries. I worked on them one at a time.

It was very important that the source material was the real source material. I could have drawn them, but then it just becomes, like, purely my hand, my hand, my hand.

I took the tapestries, I blew them up 20 feet by 20 feet or something big. Throw it over the forklift, go up 20 feet, I laid them on this canvas; just take this automatic stapler and just hit it. Bam, bam, bam, bam, bam. I wouldn’t worry about how to hang it or the hanging mat. I didn’t care about any of that.

And then I began to lay the layers of my artistic architecture on top of it, building layer upon layer upon layer. I would start with paper. I would draw the shapes with the paper. Now, as soon as you start drawing with the shapes, with the paper, you’re going to lose the figuration. It’s already going to move to abstraction. On top of that, lay caulking, infuse it with color, and start to draw with that. And a layer of black paper in between the caulking. By the time you get to the fourth or fifth layer, that source material is pretty much gone. And I would watch that tapestry go from figuration to abstraction or get caught right in the middle. And now you’re playing to the layers that are embedded in the work. But it’s all in your mind. I have to remember: third layer, caulking, fourth layer, black paper, fifth layer, caulking with color. Or I take little notes. I write them on the side.

If you walked in and you saw it, you would just see basically a big, heavy monochromatic thing with nothing. It was like before you start digging out an archeological dig, it’s just sand on the surface, and everything that you want to know about it is underneath. Then I would climb back up in the lift, and I would take acid, and I would pour it from the top. The acid is the dynamite for me. When I pour the acid on it, it actually gets inside of the different layers and releases them. That would go down and it would just curdle and bump over the different surfaces, and it would start to bleed together and would turn this gold color. Then I take my finger to peel back and find the different layers. I would watch the little characters come out. I let a dog peep out, and I let some plants peep out. Sometimes I’ll peel, sometimes I’ll sand, and sometimes I’ll just leave it very raw with just the different layers.

“The Unicorn Purifies Water,” 2020. Mixed media on canvas 365.8 x 401.3 cm : 144 x 158 in. © Mark Bradford. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures

Chapter 10: Finishing the tapestries

MARK BRADFORD: I knew when I was done with each one of them. How do you know when a relationship is done? You just know. It may take you a minute to get out of it. But when that person walks in the room one day and just looks at you, you kind of know. Like, “You know, I’m done.” Now, it may take you a year or two to get out of it. Or you just know. You just know in yourself when something is done. Whether it’s a relationship to a person, a job, a neighbor, you’re just like, “You know what? I’m done.” It’s the same thing with the painting. I know when it’s done. Now I have to finish it up and tidy it up, but I know when it’s done. I’m happy when it’s done to tell you the truth.

I always say that you can tell how much I’ve worked on it by how heavy they are. Some paintings I do are very light. And then sometimes you have done so much to that surface to bring it up to life, it’s just Frankenstein. It’s just Frankenstein. It’s just Frankenstein. Oh God. I mean, it’s like vampire painting at that point. You have to resurrect from the dead.

I have a painting in my studio now called Tulsa Gottdamn. It is not only a vampire; it’s like Nosferatu. Oh my God. He is the vampire of all vampires. I’m serious. When he started breathing, I ran out of the room. I was done. I was like, “Get me out of here.” I was so tired of that painting. Oh, but he’s breathing.

“Tulsa Gottdamn,” 2021. Mixed media on canvas 213.4 x 274.2 x 5 cm : 84 x 108 x 2 in. © Mark Bradford. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures

For the first time, I was able to abstract a tapestry and make it in my own voice.

As I peeled away the surface, I kept saying to myself, “Mark, I think he might’ve gotten it. I think you might’ve gotten it. Finally.”

The surface looks abraded. It looks, like, as if you took the original tapestry, but if it was left outside a really long time and still had the ghost of the original. You can see the cage. But the unicorn itself has actually been more abstracted. The cage itself is almost falling into the fauna and flora around it.

It reminds you of an old friend you used to know, but he’s kind of changed. Not exactly like this, but I’ve seen this, I think. A memory.

It’s so wonderful when a painting is just generous. From the beginning of the canvas on the wall to the first layers that you put on it, it’s right there with you. The tapestries were generous. The gods were shining down on me when they knew I needed a little help. They’re like, “You know what? It’s a pandemic going on. And everything is real bad. I don’t think this artist could just take it if everything falls apart.”

A detail from “The Unicorn Rests in a Garden,” 2020. Mixed media on canvas 365.8 x 279.4 cm : 144 x 110 in. © Mark Bradford. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Joshua White/JWPictures

Chapter 11: You are an artist

MARK BRADFORD: I was standing in line at Home Depot, and a guy tapped me on the shoulder, and he said, “You’re not going to believe this, but there’s a guy, he kind of looks like you, and he gets all this trash, and he makes paintings out of it. He’s famous. Can you believe that? Is that you?” And I said, “Well, would I be standing in line at Home Depot?” And he was like, “Yeah. You right. You right.” Oh, that was funny.

Artists belong wherever we decide to go. Whatever room we decide to be in, we have the right to be there. Wherever you want to go, go. We don’t belong at the fringe. We don’t belong in the center. We belong wherever we want to go. We can be as fluid as anybody else. There’s as many different ways to be an artist as there are people. And no matter what you’re doing to pay your bills, if you decide that you’re an artist, and by day you’re a lab tech, don’t let anybody take that away from you. Don’t let anybody assign meaning to who you are. Never. You’re a lab tech to make money, but you are an artist. You decide if something has value; you don’t wait for somebody else to assign value to it. If you wait for other people to assign it, you will never have it. Never. I’ve made a lot of mistakes. And I still make a lot of mistakes. But I’ve never waited for somebody else to tell me that my work had value, that I had value, that my ideas had value. If I decide that they have value, they have value.

Unicorn imagery combines with street advertising in this installation view of ‘Mark Bradford. Àgora,’ Serralves Foundation, Porto, Portugal, 2021. © Mark Bradford. Courtesy Serralves Foundation. Photo: Filipe Braga.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Mark for sharing the story of this creative journey with us. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you found things in it that you can bring into your own work. Maybe it’s the way Mark describes searching for what he needs creatively as “finding the milk.” Or maybe it’s the way he learns, bit by bit, to think of himself as an artist — and take his work seriously without taking himself too seriously. Or maybe it’s all the practical parts of his routine, the simple daily things he needs to fuel his creativity.