Trust your instinct

“It’s too long. It’s too sad. It’s not danceable.” Just some of the feedback salsa legend Rubén Blades got from DJs and record labels about his iconic song “Pedro Navaja” on the album “Siembra,” which went on to sell 25m copies. That’s more than the Beatles’ “White Album.” And his story of creating this album with Willie Colón is a testament to three words: Trust your instinct. Don’t let anyone throw you off a creative vision you believe in. But also don’t assume that instinct is innate. You hone your instinct through a lifetime of reading, listening, looking, doing. And don’t believe anyone does it alone. Trusted collaborators are always a powerful, sometimes invisible force driving any creative vision, in any field.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: I never doubted

- Chapter 2: The Spark

- Chapter 3: The struggle

- Chapter 4: The creative foundation

- Chapter 5: I finally write the song

- Chapter 6: The story of “Pedro Navaja”

- Chapter 7: Writer’s Block

- Chapter 8: What if they hate it?

- Chapter 9: A song for the people

- Chapter 10: A helping hand

- Chapter 11: Writing the arrangement

- Chapter 12: The reasons it will fail

- Chapter 13: The epicenter

- Chapter 14: Proving them wrong

- Chapter 15: Life is full of surprises

Transcript:

Trust your instinct

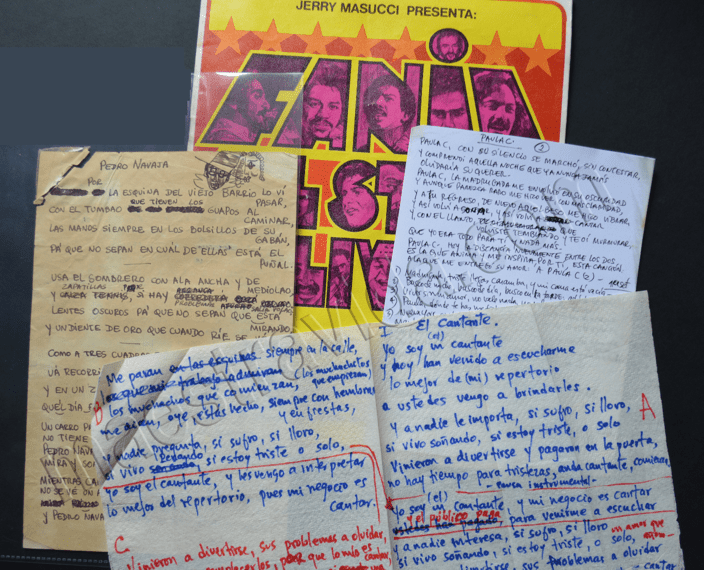

At the Ruben Blades Archives at Harvard, among the many feet of archival material, is a collection of handwritten song lyrics – including the first “Pedro Navaja.”

Chapter 1: I never doubted

RUBÉN BLADES: Willie Colón and I were summoned to the presence of Jerry Masucci, who was the head of Fania Records, the biggest salsa label in the world. When we walked into the office, there were three other people in there. I didn’t know who they were, and they turned out to be the three top DJs of New York. And they played the record, and when it was over the three DJs said, this is the worst album we’ve ever heard. The songs were depressing. The songs were too long, especially that song about that man and that woman. People don’t care about those things, they don’t wanna hear that. And one of them said to Masucci, “If you release this record, this will be the commercial death of Willie Colón.”

I didn’t say anything but you know I wasn’t worried. I wasn’t worried about it at all. I didn’t believe them, I just felt you can be DJs and you can have all this power, but that doesn’t make you smart. It just makes you DJs. I’m not having a debate with you, that’s your opinion, okay fine. And discussing opinions is like arguing with a drunk. I never doubted what I knew, I figured this is a story. If I like the story I am sure others will like it too. They did not convince me to doubt myself.

JUNE COHEN: That’s Rubén Blades, one of the world’s most iconic salsa musicians. And he’s about to tell us the story of writing “Pedro Navaja” – the song that changed salsa music forever. It anchored the album Siembra, which we now know as the best-selling salsa album of all time, with more than 25 million copies sold. That’s more than the Beatles’ White Album.

So this is a very specific story about an underdog song in the 1970s that the record label said was too long, too sad, and too different. But what you’ll hear in Rubén’s story is universal, for any creative in any field at any time.

As Rubén takes us on the journey of writing and releasing “Pedro Navaja,” you’ll hear how to trust your instinct, and hold tight to your creative vision when you believe in your own ideas. You’ll also hear how to hone your instinct over time – by seeing life as a continuous process of reading and learning. And you’ll hear how to go farther and faster in your creative work, by trusting others; because as Rubén’s story bears out: You have to trust your instinct, but no one succeeds alone.

And here’s what you need to know about Rubén. He grew up in Panama, and earned a law degree there. But moved to the U.S. after a corrupt regime came to power. He was working in the mailroom at Fania Records in New York when he wrote this album, which he released with the salsa legend Willie Colón. Since then, Rubén’s released more than 50 albums, winning 14 Grammy and Latin Grammy awards. He also ran for president of Panama. But that’s an entirely different story.

“Pedro Navaja” was Rubén’s breakout song. And even if you don’t know it, you might recognize the song’s origins. It’s a reinterpretation of the popular song “Mack the Knife,” which comes from the musical The Threepenny Opera – which was itself reinterpreted from an 18th-century play called The Beggar’s Opera.

I should also add that Rubén’s last name is commonly pronounced Blades. But he tells us it’s actually pronounced the English way: Blades. Which is pretty perfect for the guy who wrote a legendary song about Mack the Knife.

The piano you’ll hear in this episode is our composer Hil Jaeger, who’s playing along with the story. And for visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com/rubenblades.

Chapter 2: The Spark

RUBÉN BLADES: I was 12 years old in Panama, every house had a radio, and the radios were on all day. Music was all over the place. I grew up listening to music from all over the world. And in 1960 I heard Bobby Darin. He recorded this song called, “Mack the knife.” It wasn’t expected to be a hit for Darin at the time, Dick Clarke who was like the guy in rock and roll told him not to record it. Because he felt it was a mistake. And it became a huge hit. And I love the song.

The energy, the attitude, the insolence, I could sense that even though I didn’t understand the lyric. There was a, “hey” that kind of thing. Like “what?” He was singing it like that, “what? So what? What are you looking at?”

Sometimes there were parties in the neighborhood and then the guys would be there. They would say, “Hey Rubén sing- sing Mack the Knife.” And I said, “Nah.” ‘And then they would say, you know I could do lip sync. Thinking I was repeating what he was saying, I had no clue what he was saying. So my lips probably were not even following the correct pronunciation. But they thought it was very funny ’cause I imagine his mannerisms.

Cause I had no shame. And then they would give me like 25 cents. And that meant I had access to sodas.

I knew enough of the Darin version to understand that he was writing about the street. And that fascinated me, the fact that he was writing about something that was happening in the city that had nothing to do with the usual subject matter of songs. Which was all love, love, love, this was different. But I like this energy, I felt something about the song. I wanted to do something in Spanish. I don’t want to copy what he’s doing, so I will write my own song, and that began the process. 1960 when I was 12.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice that detail Rubén shared about Bobby Darin’s version of “Mack the Knife”? So apparently Dick Clark told Bobby that it was a huge mistake. But Bobby trusted his instinct, and he was right. And that’s the theme you’ll hear again and again in Rubén’s story. Whatever your field, you have to hone your creative instinct, and then trust it.

Chapter 3: The struggle

What do you do if no one gives you a break? Find any opening you can. And keep your instrument close by.

RUBÉN BLADES: I was studying law in Panama National University. I was told in no uncertain terms that I could not be a musician and a law student by my Dean. I left because I did not want to be a lawyer under a dictatorship. My family had gone to Florida the year before. And I went to join my family. They were going through a lot of economic problems, my father had no job. I had my three little brothers, and I mean I felt useless. My diploma meant nothing there.

I had written a couple of songs that had been recorded by Fania label stars. So I figured, I can ask them, “Give me an opportunity to write songs for your label stars.” So I called Fania records, and I asked them if they would hire me as a composer. They said, “No.” I asked, “Do you have any openings there in the company?” And they said, “Actually today just got an opening in the mail room.” So I left.

Well the mail room in the Fania recording label was a very small room. Even by New York standards, and it was filled with records and tapes. I had to put each album inside of an envelope and get the address of the radio station. All of that mail was so heavy that the post office refused to pick it up. So I had to bring it myself. They had like, one of those rinky dinky wagons. Always with a bad wheel, and I had to push that thing from 57th and Broadway all the way to, uh, 52nd and 9th before the post office closed. It was no fun in the winter.

I kept my guitar in the mail room, sometimes you don’t know when you’re going to have the inspiration. You know I’ve written songs on top of Chinese menus, I just write when I feel like it. And I’m not sure when that’s going to happen.

Chapter 4: The creative foundation

How can you build your own creative instinct? Train it, feed it, inform it – and then trust that it won’t fail you.

RUBÉN BLADES: My grandmother and ma taught me how to read when I was very young. I was four or five. I was reading absolutely everything that fell into my hands, everything. My mind was constantly imagining things as I read. The descriptions that I received from my reading, I had to imagine them. I had to imagine the colors, I had to imagine the people. Were they tall? Were they short? Were they thin? Were they obese? Were they old? Were they young? You had to think about all of that. So I was reading and constructing. I learned a lot from many other people. The intense clarity and honesty of Carmen, the way to express ideas as fluidly as Gabriel García Márquez. I’d love to be as playful as Borges, the vision of someone like Faulkner.

They inspired me to do my own things. Every single thing I ever read informed some area of my brain about the possibilities. Read as much as you can, because every single line is somehow informing you and feeding you. What you’re doing is you’re educating your insights, your innards, your instinct. And when the situation arises, trust your instinct, because your instinct, having been groomed, will not fail you. Trust it, and don’t be upset or worried about the consequences of trusting your instinct, because your instinct is informed. Always follow that, and that’ll become the solid foundation over which you will walk the rest of your life.

Chapter 5: I finally write the song

How do you capture an elusive idea? With confidence and patience. Don’t chase it.

RUBÉN BLADES: When I sat down to write, “Pedro Navaja” I wasn’t following some call that said, today my son you will write “Pedro Navaja.” I didn’t hear any voice, it’s just all of a sudden I sat down just naturally. It was the time to do that. I have numerous notebooks where I would write the idea down. I let them breathe. I don’t chase them. I go back to them at some point. You think you’re stumped, and it’s just, you’re chasing the deer. The more you chase it, the further away it’ll go. Let the deer stop on it’s own, and then you’ll find it. Just don’t chase it. And what happens is that, unconsciously you’re thinking about it. Whatever brought the idea or the concept, or the, that little light, it’s working itself without your help, without your prodding, without your impatience. And then, when I go back to it, usually, I surprise myself in how clearly now I can see what was not apparent to me when I made the note. That is why I take so long to write, ’cause I had certainly thought a lot about it. The first time I heard Bobby Darin, it was 1960, and in 1974, ’75, writing “Pedro Navaja.” Your subconscious has already done all the work. One day, I sat down, and I wrote the whole song. I had the original of what I wrote. There’s only one scratch. I had the song in my head.

Chapter 6: The story of “Pedro Navaja”

How do you create a work that endures? Write from what you know, from the streets where you live.

RUBÉN BLADES: Love songs are written when love begins and when love ends. You don’t hear boleros love songs in the middle. People saying, “Oh, I’m doing really well. We’re very happy,” you know, you don’t hear that. It’s the beginning and the end. And I thought, okay, what about telling a whole story in a song? Beginning, middle, and end. Okay, he’s in the street, now what? Okay, he’s walking. What happens when you walk in the street? You see things. In that sense, I’m the character. I’m walking, and I just kept on writing what I saw as I walked.

I’m gonna create this story based on a street guy, because that’s what the figure of Mike Heath was. When Darin sang out about was a thug, a guy from the street. And then, trying to imagine it. Okay, where is this happening in the street? Where? In the street where you live. Don’t write about stuff you don’t know, write about stuff you know.

In those days, in Panama, there were two gangs that were very active. One was called Zapatillas Negras, which means black sneakers, and the other one was called Dientes De Oro, gold tooth. So, I picked up the sneakers and the gold tooth, and I gave those characteristics to this guy.

And then, I went to 42nd Street, and I saw the pimps there, the men who lived off the women, with the big hats and they had, uh, jackets. And since I was in New York, I figured okay, so I gave him my jacket, and I gave him my jacket for practical reasons also, so you wouldn’t know what he had in his pockets. I continued to imagine: what was this story? So, this guy’s walking, he’s in the street now, then what happens?

Okay, then somebody else is walking in the street also. There’s gotta be some confrontation of some kind. So, then I came up with the idea of the woman who’s also working the street. So, now the confrontation is gonna be between a man and a woman, that’s a conflict right there. I made a point to not fall into the trap of victimizing the woman, ’cause up until that moment, women, they were not protagonists. They were always victims. So, I figured you know what, this woman is not gonna be a victim, solely, she’s gonna defend herself, and she’s gonna have the last word. I’m gonna give the woman the last word in a song, which popular songs, salsa songs, at that point, I don’t remember it happening.

She’s the one who shoots the assailant, Pedro, after Pedro stabs her. And I said, “Make sure that even in the worst scenarios, you give people equal opportunity.” Don’t base your songs just on one point of view or one, one overwhelming force. Life is much more complicated than that. It means life provides surprises for you.

I said, “This song, it’s about two people whose lives are gonna be intersecting and changing each other.” This song is about New York, the streets of New York, but it’s also about the streets of any area in the world where people are forced to fend for themselves in the best way that their limitations can provide.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice the words Rubén used to describe his creative process? “Write what you know. From the streets where you live.” He comes back to this theme over and over, because when you start from what you know – in any creative field – you can trust your instinct. You can trust the audience will be with you. And you can create something totally new.

Chapter 7: Writer’s Block

What do you do when you run out of ideas? Open a newspaper, and start asking questions.

RUBÉN BLADES: Gabo once told me, “There’s no such thing as writer’s block.” And I said, “Well what do you do when you’re staring at a page?” He told me a story that you can actually go to the classified ads of a newspaper and see what people are selling. For instance, a bird cage for sale. And then you think, what happened to the bird? What kind of bird was it? Did the bird fly away? Did it die? What did he die of? Was he killed? Was he eaten by a cat? What’s the cat’s name?

All of a sudden you can write a whole story about what happened to that bird (laughs). Yeah it’s like, you can just go on, and on, and on. Like Mort Sahl the comedian, he went to a club, got the paper, opened it, and began to riff. That was it, so if you all of a sudden run out of ideas, buy a paper.

We have material all around us, so there’s really no reason why we should say, oh I don’t know what to write about.

JUNE COHEN: You may have noticed at the beginning of this chapter that the advice didn’t come from Rubén himself. It came from his friend Gabo, and Gabo, to you and me, is Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the Nobel Prize winning author of Love in the Time of Cholera and 100 Years of Solitude who seems like a pretty good source for writing advice.

After the break: Rubén performs “Pedro Navaja” live for the first time – and before it’s quite ready

Chapter 8: What if they hate it?

RUBÉN BLADES: I never, ever, ever, ever, ever have written anything in my life, thinking, oh, people are going to hate this or people are going to love this. I just write it. If you don’t like my song, don’t listen to it. That’s all you gotta do. Oh, “Rubén Blades is the worst singer in the world. Don’t listen to me, and you will not have that nightmare in your life, you know. Go listen to somebody else. Am I gonna be offended by that? No. Why? Why would I be offended if you don’t like how I sound? That’s you. There are other people who do like it. Unanimity is practically non-existent. So, you know, live with that. Not everybody is gonna like you, not everybody is gonna like what you do. That’s it, that is a fact of life.

Chapter 9: A song for the people

How do you know if your work will resonate? Put it in front of an audience, even if it’s not quite done.

RUBÉN BLADES: I went to Puerto Rico to play with a local band there called La Solucion, so we went there and we played 21 shows all throughout the island. We were gonna play in graduation parties, proms. And this is, like this was the people. This is it. All ages, all walks of life. Like, neighborhood. But I didn’t have a lot of material, so we played the material that we had, and sometimes it was a little time left. And I said, “I’m gonna present this audience with “Pedro Navaja,” but just the lyrics.” I didn’t have an arrangement yet.

So, I spoke to the conga player of the band, and I said, “You know what, just give me a little beat,” and I sang the song, but only with a conga, and they loved the song. They loved the song. I said, “Of course they’re going to like it, because they see it. They’ve seen it, they’ve seen this happen before.” And they just reacted to the whole thing about … because that’s their life. Yeah, life is full of surprises, life is unexpected, you never know what’s gonna happen. It could be good, could be bad, but it could be better.

I always, always, to this day, I am part of the public that comes to see me perform. I don’t feel that the public has one way of looking, and then I have another way of looking. I am one of the public, so I simply identify myself with the people.

Chapter 10: A helping hand

How can you go farther and faster creatively? Trust others to pick up where your instinct leaves off.

RUBÉN BLADES: Success is never the product of one person alone. Nobody can succeed on their own, I don’t believe that to be true at all.

Whatever I am and whatever success people feel I have, has come as a consequence of a concerted effort of many people.

We have fingers, and we have a hand. If I depended on my finger only, I could not do anything. I could not lift things. I could not make a better life for myself, with my finger. With my hand, I can. That is success. Success is a hand, not a finger. So in the band, we are a hand.

I started working with Ray Barretto, and I brought Barretto, “Pablo Pueblo,” and he didn’t wanna do it. A song like “Pedro Navaja,” Barretto would not have touched. When I came out with these ideas of these songs that had been rejected by other band leaders, Willie saw the potential. Willie Colón plays trombone, he’s also an arranger, one of the true icons of salsa music. He started very young, 14, 15. Hector Lavoe joined Willie Colón’s band, and they became one of the most famous groups in salsa history. Very intelligent guy. And what is intelligence? Intelligence – read between the lines. He was smart enough to understand that there might be something in this. We joined forces, and because he was an established band and an established name, the association with Willie Colón gave the songs the opportunity to be known in, immediately by incredible amounts of people, millions of people. And that absolutely helped me to become known as a composer and as a singer.

Chapter 11: Writing the arrangement

When should you break the creative rules? When you need to prove a point … and you’re prepared to defend the decision.

RUBÉN BLADES: I don’t write music to the point of writing an arrangement, I never had that advanced studies of music. So, I called upon a friend, a trumpet player, wonderful musician and wonderful person, Luis “Perico” Ortiz, to write the arrangement for “Pedro Navaja.” I explained the song to him, I said, “Don’t think of this as a straight-up salsa song. Furthermore, I want you to interrupt the flow for the dancers.” Dancing requires to follow the clave, which is this. This is the clave. And dancers use that as a sort of guide. If the clave is not going with the rhythm, dancers are lost. So, when the mambo comes, I ask Luis, “Break the clave. Break it. I want the dancers to all of a sudden stop and feel like, what the hell happened?” It changed, because lives are changing in the song. The mambo is the instrumental part, it’s the moment where any salsa song shows what it is about. I want that moment broken. I want people to go, “What the hell happened?” Because that’s the question I want people also to make of the song, “what the hell happened here?”

You have two people in the street, and then you have a drunk that thanks God, as if God was his accomplice, after two people were killed for this, and then he moved on. Life moves on. It’s like, hey, get over it, you know. Get back to the clave and keep on moving because that’s it, you have to move. Life is full of surprises, okay, now move. Keep on moving. And Luis “Perico” Ortiz did a wonderful, wonderful arrangement, and he got a lot of criticism for it.

When we were playing that song with Willie Colón’s band, at the beginning, the rhythm section, which was, uh, Milton Cardona, God bless him, and in the bongo, Jose Manuel Junior, they weren’t very happy about the breaking of the clave ’cause they’re like, real standard defenders of the clave musicians.

And I could understand their point, but I wanted them to understand that my point as a writer was to create that tension and break it, break the tempo in that moment, have people stop and have to come back to it again. So, as life is, in that moment, you stop, and then you pick up the clave again, and then you go back to your groove. It’s not the end of the world, is what I’m saying. Life continues.

Chapter 12: The reasons it will fail

What do you do when the gatekeepers won’t let you in? Believe in what you know.

RUBÉN BLADES: Masucci said, “What song do you recommend for the single?” And I said, “You have seven stones, cast the stone you like,” and I left. The radio programming was based on selling ads, that’s what the radios do. They sell things. The program, it went like this: Songs are, like, between two-and-a-half minutes and three minutes, and then we put ads. So, they divide the hour in terms of how many ads they’re gonna place. If a song is like “Pedro Navaja” – instead of being two-and-a-half minutes or three minutes, it’s seven-and-a-half minutes, you’re eating in their ad’s time. So, they don’t want songs that are long because they don’t care about the song itself, and they don’t imagine that anybody in their audience, the audience that they’re trying to sell something, is concerned about the song duration.

They think they want things short because, you know, people, people don’t have attention spans. Say, “Well, maybe people like you, but not everybody is like you.” I think the public is far more intelligent than people give them credit for.

Jerry Masucci knew that we had been selling from the album that we had done before, so I’m sure he had misgivings. For him, it was smarter to put the record out and see what happened, and the album was the biggest earthquake in salsa that ever happened.

Chapter 13: The epicenter

RUBÉN BLADES: It was a stadium with 40,000 people. It was the first time that we were getting a reaction from the public, not from sales reports. With Willie Colón’s band, the same band that I played before with Hector Lavoe, and they weren’t that sure that I could actually fill the shoes of Hector Lavoe, who’s a huge star. The moment that the song started, the place just lit. You heard the roar. We’re talking about thousands and thousands and thousands of people, just the roar: “Ahhh” you know. “Ahhh” (singing) they knew I was coming. And the electricity in the place, when the whole stadium started singing the song back. They sang the whole song, and Willie and I just looked at each other, I mean, and the band is going like, “My god look at this.”

But when I looked at Willie and Willie looked at me, I mean we were looking at each other more like, saying, “see? Wow, but see? Yeah, here it is. This is it, this is what we said. This is what we expected.”

I just saw it, and I felt that internal blessing that says, yes good. And move on, move to the next thing. Don’t stay there. You saw it, you enjoyed it, move on.

Chapter 14: Proving them wrong

RUBÉN BLADES: About 30 years later I’m in New York, I’m crossing the street, and I see one of the three DJ’s that was in the room, and I hadn’t seen him in a long time. And I said, “Hey how are you?” And he saw me, “Hey Rubén, yeah yeah.” And he wanted to talk, and we’re in the middle of the street so I went with him to where he was going. And then I stopped and he talked and said, “How are you?” I said, “I’m fine, how are you? You look good.” You know, the usual things that you say to people when you have not much to say. And then he said, “You remember that day when you were in the room with Willie Colón, and we were listening to Siembra for the first time?” And I said, “Oh yeah, I do remember absolutely. Unforgettable.” And he says, uh, “Do you remember what I said?” I said, “Yes I do.” And he said, “I told you that song was gonna be a huge hit. I told everybody that’s the best record, and that song was going to be a hit.”

And I heard him, and I looked at him and I thought, I’m not going to say anything but agree with him. Because it’s really pointless for me to say anything else. If that’s the way he remembers it, okay. It helps him sleep better, I’m not going to break that spell. I don’t doubt what I know, why should I hurt him? Why should I hurt him now and say, “You know you were wrong?” It’s like hey, it had a happy ending, enjoy. And you know, it’s an interesting thing. You remember when the critic who destroyed Van Gogh’s work and said, “This was an awful like- painted by somebody who doesn’t have any idea of painting.” Who the hell remembers that guy today? Who remembers that guy? Nobody.

Chapter 15: Life is full of surprises

RUBÉN BLADES: The whole point of the song, “La vida te da sorpresas,” I think the core of “Pedro Navaja” is that. That life is full of surprises, and at the end of the day no one knows exactly how life is going to turn out to be. Some people feel that nothing should be tried for the first time, ever. Don’t pay attention to that. Don’t defeat yourself off the bat by not trying. You have to try, you can surprise yourself by being hopeful. Because life surprises you every day so why not for the good? There’s always room for mistakes. There’s always room for success. There’s always room for failure. But there’s also always room for redemption.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Rubén for sharing the story of this creative journey with us. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you found things in it that you can bring into your own creative practice.

Whether it’s the way Rubén trusted his instinct again and again in the making of “Pedro Navaja.” Or the way he honed his instinct over years of reading books and listening and writing music – going back to that radio-filled neighborhood in Panama where he grew up.

It might be the way he thinks of himself as part of the public he serves – even after decades of being a star. Or it might be the way Rubén thinks about leaning into the strengths of others. As he said, alone, he’s just a finger. And it’s hard to get anything done with a single finger. But with collaborators, you have a whole hand.