Great collabs start with trust

“I want to make this into theater, in a way that’s never been done before.” When Kamilah Forbes first reads “Between the World and Me,” by her friend Ta-Nehisi Coates, she’s moved, shaken, gutted by its truth and beauty. She dreams of presenting it at Harlem’s Apollo Theater, a legendary space for Black art and excellence. First step: convince Ta-Nehisi. Spark & Fire follows the journey from book to stage to HBO – during a pandemic – in a story of collaboration and trust, joy and challenge.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Alone with a book

- Chapter 2: The four-hour wait

- Chapter 3: Now I have to make it

- Chapter 4: Help arrives

- Chapter 5: What I knew from the beginning

- Chapter 6: How it comes to life

- Chapter 7: The afternoon before opening night

- Chapter 8: Opening night at the Apollo

- Chapter 9: The pandemic. And then, the protests

- Chapter 10: Back into the forest

- Chapter 11: A film – in record time

- Chapter 12: An audience outside the Apollo

- Chapter 13: What this work means now

Transcript:

Great collabs start with trust

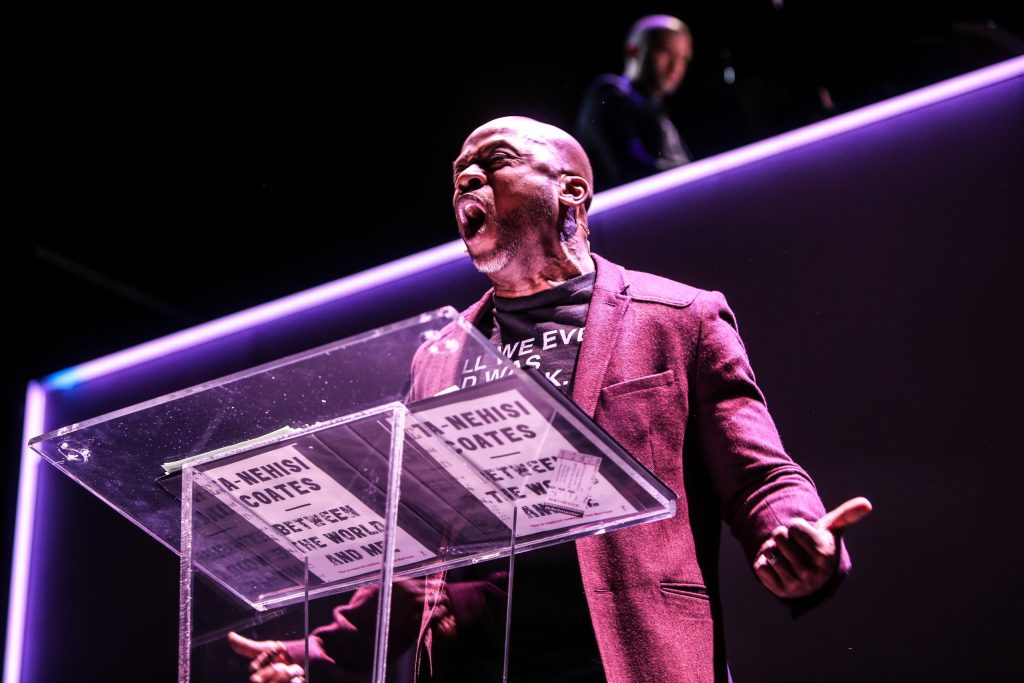

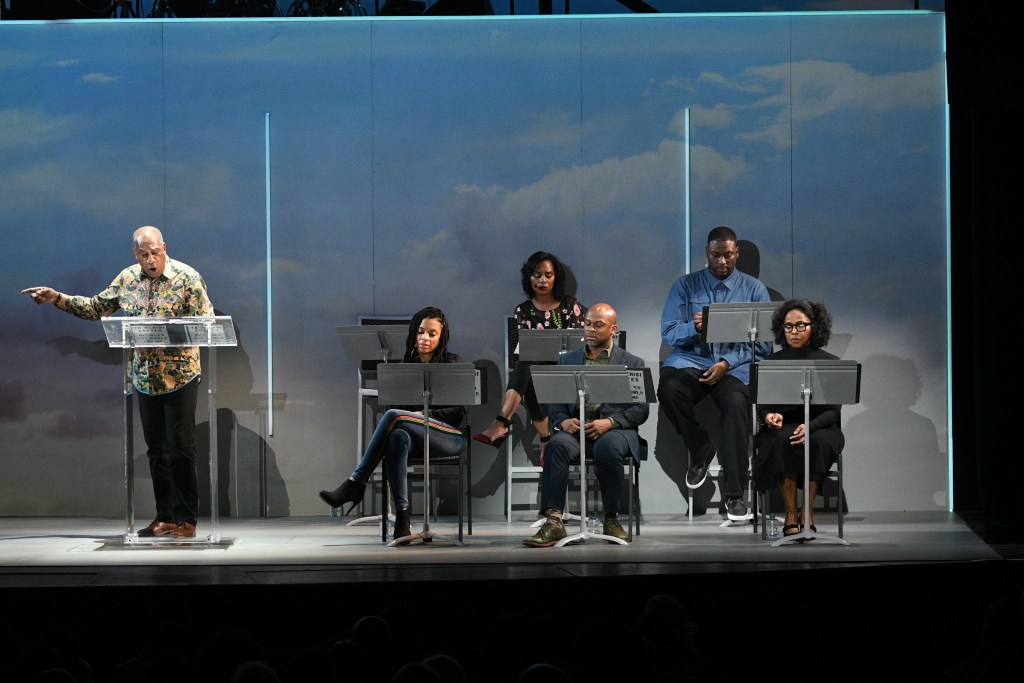

Marc Bamuthi Joseph (with Jason Moran on piano) during “Between The World and Me” when it was presented at the Kennedy Center after premiering at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Photo courtesy of Jati Lindsay

Chapter 1: Alone with a book

KAMILAH FORBES: Being away from home in a hotel room, I read it in one night, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me. Just the quiet of being alone with these words and with these very big ideas … it stirred so much in me that evening, from joy to rage to loss.

The format of the book was told as letters to Ta-Nehisi’s son, Samori, talking about him in a way and his own frailty and vulnerability just brought up so many emotions for me. I felt like my heart was gutted out of my soul and then I was somehow assembled back together.

I was highlighting lines like, “Oh my God, I can’t believe … Oh my God, this line.” Then just getting washed over in just the beauty of the writing, the beauty of the poetry.

That’s when the idea started and the wheels began to really turn. I want to make this into theater in a way that it’s never been done before.

JUNE COHEN: That’s Kamilah Forbes, executive producer of the Apollo Theater. And she’s about to tell us the story of adapting the book Between the World and Me — to a stage production — and then an HBO film.

It’s a specific story about adapting the beloved, best-selling book by Ta-Nehisi Coates — whose lyrical language helped galvanize the Black Lives Matter movement. But what you’ll hear in the story is universal — for any creative in any field at any time.

As Kamilah takes us on this creative journey — you’ll hear how great collaborations are inspired when you cultivate trust. You’ll hear how Kamilah slowly persuaded Ta-Nehisi to trust her with his work. And how she in turn trusts each collaborator — by giving them just a kernel of an idea — and the space to bring their own creative gifts. You’ll also hear how she methodically builds community in her cast and crew — in order to inspire their best work.

Here’s what you should know about Kamilah Forbes and the book. Kamilah’s a long-time producer who created the Hip-Hop Theater Festival and produced Def Poetry Jam for TV. She’s directed dozens of plays including several on Broadway, and she’s now Executive Producer at the legendary Apollo Theater in Harlem.

You should also know that Kamilah and Ta-Nehisi are old friends. They met at Howard University, and they both knew Prince Carmen-Jones, their charismatic classmate, who was killed by the police and whose death figures prominently in the book.

Between the World and Me was first performed at the Apollo in 2018, to huge acclaim. And then adapted to a film that Kamilah created in under three months. It premiered on HBO in November 2020.

The original music you hear is our composer Hil Jaeger, on prepared piano. For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com/Apollo.

This story was recorded with Kamilah from her home, during the pandemic. And you will occasionally hear her daughter in the background.

Kamilah Forbes on the Apollo stage. Photo Shahar Azran

Chapter 2: The four-hour wait

What do you do with the first glimpse of an idea? Share it. And then stay with it.

KAMILAH FORBES: At one point at 3 AM, I remember just waiting for 7 AM so that I could text Ta-Nehisi at a reasonable hour. The first phone call was very inarticulate, “Oh my God, I can’t believe you wrote this. Oh my God. I’m feeling this, I’m feeling that.”

I could not physically get my body together to describe to him what I was proposing. And I remember him just sort of pausing, like, “Okay.” Like I don’t know what that means. I don’t know how to respond. He says, “I wrote this as a book because that’s how I envisioned it,” right?

At that point I knew, I was like, “Okay, let me just back up. I’m really overly emotional. I’m very enthusiastic. He doesn’t know what to do with this yet. I get it.” And quite frankly, I wasn’t really clear on what I was asking. I just knew I had an instinct, and I wanted to respond to that instinct.

And so I kept reapproaching him week after week, month after month. I would send these emails like, “Hey, hey, I got an idea. Whenever you’re ready.”

It really took several months of really trying to form the idea, letting it marinate, taking it from just that bit of a kernel of an instinct and really putting shape around it. Or like I like to say, put some meat on the bones.

I started to put together just a series of one pagers. I put together one page of potential cast members, potential musicians, what would the stage be assembled? And even then I approached again, and he was like, “Okay …” I continued to have conversation and dialogue. Several months later, he was like, “Yeah, sure, go ahead. Go ahead, do it. I feel good about it.”

Planning for the show began with a series of one-sheets and technical plans.

Chapter 3: Now I have to make it

How can you avoid those initial fears? Actually, you don’t want to.

KAMILAH FORBES: There was a lot of newness that was swirling in my life right at that moment. This was right before I had started at the Apollo. I had literally just had a baby. My first day of work, my daughter was three months old.

Our PR director at the time had released, “Apollo is going to develop this work by Ta-Nehisi Coates into theater,” and the New York Times quickly picked it up. And she came running into my office like, “Oh my gosh, like the amount of noise that we’re getting on this one thing, this has not happened, especially for a work of theater that we’ve done.”

I got a call from Phillip Hamburg, who ran the Sundance Theater Lab at that point. And he was like, “Oh, Kamilah, I just read this amazing thing that sounds so amazing.” And I was like, “Uh huh.” knowing that all I had at the moment was this kernel of an idea and a book that everyone revered and loved.

And I was like, “That’s exciting,” but then I was also like, “Oh, crap. Now the expectation, the bar. Now I’ve got to go build it. Now I’ve got to make the art.”

That feeling of, “Oh crap. I got to make it,” is a feeling that happens on every project. You know, this is new terrain, this is a new journey. I’ve had it on every project that I’ve ever worked on. It’s like you’re walking into a forest, a very dark forest, and you’ve got to find your way to the other side.

All I can see is darkness. But as you start to get in that forest, you can start to begin to feel, “Okay, wait, there’s a tree here. Okay, wait, no, no, there’s still grass under my feet. Okay. I just need to begin to feel my way through because it’s just a forest that I’ve never been through before.” That’s the exciting piece of a journey.

I’m trying to learn to really embrace that kernel of fear, not to be scared of it. I think with every creative journey, that feeling actually is necessary. And I think when I don’t have that feeling is the moment when I should say, “Actually, this is not for me.”

When you feel like you know exactly where to go and how to do and what to move, there’s no room for discovery. Be reminded that actually this is what fuels my process. This is a reminder that this is exactly where you need to be.

Kamilah Forbes amid rehearsals at the Apollo. Screenshot courtesy the Apollo Theater.

Chapter 4: Help arrives

What do you do when all you have is an idea? Trust the process, trust yourself, trust each other.

KAMILAH FORBES: All I had at the moment was this kernel of an idea and a book that everyone revered and loved. Phillip Hamburg, who ran the Sundance Theater Lab, he said, “Look, what kind of support do you need? Do you need a residency?” I was like, “That’s exactly what I need.”

This is how angels swirl, right? This is how the universe works in my favor. We needed first and foremost a script, that’s your Bible. We had this incredible book, incredible language. I mean, arguably one of the most important pieces of literature of my generation, for sure. Then how do you form that? Having worked with so many playwrights around workshopping their plays, I knew we needed workshop time — that kind of laboratory time to really take it from a book into something that actors can easily pick up and read.

Lauren Whitehead went to the Sundance Lab a week ahead of us, and was beginning to do the work of pulling the pages apart. By the time we got here, she was wrecked emotionally. She was like, “I’ve been in this rehearsal room and basement all by myself, reading these words over and over and over again, and I am just emotionally done.”

I mean there were just days in which we would all sit around the table and we really started reading the book. How difficult is that as a parent? You can’t wear certain clothes outside because that might give certain signals to the police. And this is not an abstract concept, right? A lot of our folks who had kids around the table talked about how that talk was given to them by their parents.

We’re going over scenes, over and over and over again, and there were just so many tears. A lot of the work we did, quite frankly, happened outside of the rehearsal room, going to meals together, doing social activities together. Many times people say, “Oh, that’s just social time.” For me as a director, actually, no. This is part of my process. It was important that we built ultimate trust in one another. We were a collective. Because if I trust, I’m more willing to be vulnerable. I have a support system that will build me back up that is sitting right at this table.

Turning a beloved book into a working script begins with the process of pulling the pages apart.

Chapter 5: What I knew from the beginning

KAMILAH FORBES: I really wasn’t trying to make a play.

With plays, there are characters on stage, and although you might see yourself in those characters – you would say, “Oh. The father was really going through it.” I’ve already distanced myself from that experience: that father, that young boy. Even though you may see yourself completely reflected, there’s still an opportunity to separate. I wanted to actually remove those barriers of separation.

What if we just had multiple voices, all different kinds of people reading the language of this Black father and Black son?

I was setting out to have a community storytelling circle.

The book came out right at the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement. It had to be Black families, Black people exclusively on stage, embracing this language that so directly affected them, their lives, ancestors, future. There was something about Black people and community on stage having a space for their own celebration of joy, of identity, of resiliency, and also a place of mourning.

The book was staged as a reading, a community circle. Here, Susan Kelechi Watson reads from a passage of “Between the World and Me” at the Apollo Theater. Photo: Shahar Azran

Chapter 6: How it comes to life

What should you give each collaborator? A spark. And space to create.

KAMILAH FORBES: What was most important to me was music. When I met Ta-Nehisi, he was a poet, so I know the influence that hip hop had on him as a writer. He was a big music reviewer for the City Paper in Washington, DC. So a lot of his influences as a writer were musicians.

And music is very central to my own aesthetic as an artist. You know, when I work with Jason Moran as a musician, I’m only giving him a kernel. He’s running with it.

What Ta-Nehisi had put into words was he was able to articulate the Black experience in this country for 400 years, that was inarticulable. Music allows you to further articulate, to contract, to expand our own imagination but also our own internal emotionality.

Those moments you hear those strings come in or large piano sequences that just allows a scene to go from a small mountain to a huge valley, a huge expansive place, music does that. The power of music allows you to elevate, uplift, buoy a moment, when words are not enough.

We get this moment of going to Howard University, which is like a bastion of Black culture, intellectualism, and just joyous. And we meet Prince Carmen Jones in that same shroud of joy and beauty and love.

There’s a line in the text that talks about: he had broad shoulders and a big smile. He would greet you with such a warm smile, and when he would walk away, you would almost get a little sad because you wanted to be enveloped in that smile again.

There’s a beautiful piece of music that Jason Moran plays, which we call the Prince theme. Every time that theme is present, it is a reminder of the joy and light that he brought to the world. Not just the fact that he was also shot in the back 15 times, right. That was also a fact. But it was important that what he’s contextualized in is how we remember him. In that way, we are taking care of our audience, right?

This beautiful piece of music is a reminder of who Prince was, his light, his airiness, his joy.

Cohen: Did you notice how intentional Kamilah is about what she gives – and doesn’t give – each collaborator? She gives them a kernel, a creative spark. And then, she gives them the space to create. Ultimately, she gives them her trust.

After the break, it’s opening night at the Apollo.

“Music allows you to further articulate, to contract, to expand our own imagination but also our own internal emotionality.” Screenshot courtesy Apollo Theater

Chapter 7: The afternoon before opening night

How do you serve a collaborator’s vision? Stay true to what’s theirs, but make it your own.

KAMILAH FORBES: This is hours before 1,500 people are coming into the theater.

Roger Ross Williams was making a documentary about the Apollo and decided that he also wanted to come in with cameras and shoot and follow us. A tech rehearsal is the last time before you’re open to an audience. We had a run-through with all the techs. So that’s all the music, that’s a projection, that’s lighting, that’s sound, that’s actors on stage. Ta-Nehisi and Samari came. This was the first time – he didn’t want to read a script. He didn’t want to see anything. He didn’t want to come to rehearsal. He came then.

You know, I don’t want to disappoint him. You want him to see the work and not feel like, “Oh my God, they totally destroyed my book.”

And I remember, after he saw the run-through, I was like, “Okay, so what do you think?” And he said to me, and I remember my heart dropped. He was like, “Yeah. So that’s not my book.” And I was like, “What, what?” And I was like, “Oh my God, he hates it.” And he was like, “No, no, no, no. What you gotta understand, I’m saying this, because what you did was something so incredibly different than what I set out to do, in all the best way. That’s yours now, it’s yours now.”

There was a real empowerment, creative empowerment, right, that you want from a collaborator, to say, “No, go, go. You got it. I get it. I gave you the kernel, now go.”

And then you move on, and the show’s gotta start.

Chapter 8: Opening night at the Apollo

KAMILAH FORBES: The line was incredibly long, kind of wrapped around the block on 125th street. You’re passing our Walk of Fame with names like Lionel Richie, Michael Jackson, The Temptations. And then you would walk into the historic Apollo Theater passed the murals of Black cultural legends from Dionne Warwick, to a young Stevie Wonder. You’re walking in literal halls of a bastion of Black culture with some real Black cultural forces on stage.

Our cast was made up of folks like spoken-word artist Mark Bamuthi Joseph, Greg Alvarez Reid, Michelle Wilson, Angela Bassett, Common to Black Thought and Ledisi, Joe Morton and Pauletta Washington.

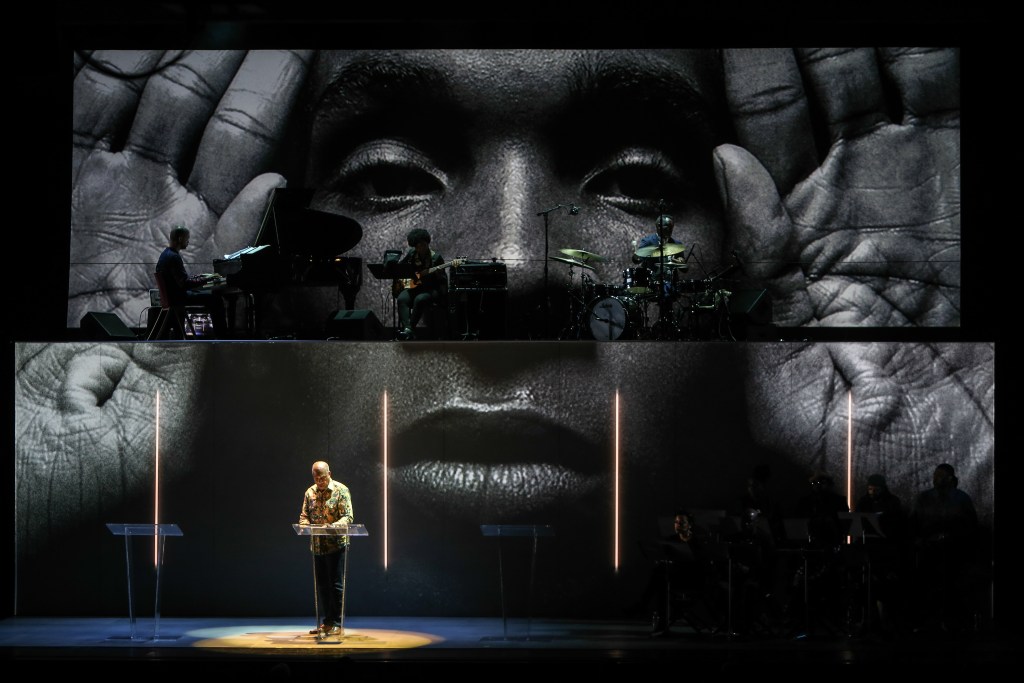

I didn’t want the musicians to be in an orchestra pit or like off to the side. We had an incredible set designer, Michael Carnahan. Michael came up with the idea, “Well, let’s just put them right above the performers. Let’s put them in the air.”

Jason Moran was on a black baby grand piano. Nate Smith was behind on a drum set, and Mimi Jones on bass.

Part of the direction is that I want to see body parts, Black, beautiful body parts. The biggest theme that Ta-Nehisi talks about in the book is the body, the attack on the body. We always have to protect our body.

We had an incredible projection designer Tal Yarden. So Tal then animated photography of these just beautiful Black people. A young man looking down at the ground and then slowly over the course of 15 seconds would slightly move and look up straight ahead.

A young five-year-old boy’s eyes and his nose and his mouth, that’s all you saw. And it would just get bigger and bigger and bigger, the innocence and vulnerability of this little boy. Again, this Black, beautiful skin that they were just literally all sitting within.

Joe Morton in “Between the World and Me” as staged at the Kennedy Center, in front of a projection designed by Tal Yarden. Photo: Jati Lindsay

The last monologue of the play was done by Ta-Nehisi. And I remember he came on stage, and the whole house stood up on their feet. I just remember tears just streaming down, this house had so much respect and reverence for him, for his language, for his journey in that moment. And the applause just would not stop. To the point he had to stop it. The show’s still going. And he literally had to put them back in their seats and did the final monologue. And then the full cast took the curtain call bow. And the audience just jumped to their feet. And it felt like such a release.

Having the audience and artists all on their feet in that moment, and the music at full tilt, was like magic. I almost felt as if the theater was levitating. It took me back to that first moment of reading the book, of joy, of rage, of resilience, of celebration, of jubilation, of despair, but all of those emotions happening all at once. And knowing that it’s happening with 1,500 people all at once, you just felt the vibration of the walls and of the floorboards. That was just unlike any other.

There’s some things at the Apollo, you only feel at the Apollo, there’s the sense of communion between the artist and audience. It happens a lot at church, but rarely in other theatrical spaces, just this constant give and take, this constant I’m here for you, you are here for me. Without both of us in this space, this work would not happen.

“There’s some things at the Apollo, you only feel at the Apollo.”

Chapter 9: The pandemic. And then, the protests

What do you do when the whole world convulses? Use your collaboration to propel the conversation.

KAMILAH FORBES: The play was also going to tour. But then COVID happened. Myself and a bunch of friends, Ta-Nehisi, Kenyatta Matthews, and Susan Kelechi, it was a bunch of other people, we would meet on Saturday nights for game night. We’d play Scattergories. It was literally our only social interaction with people, on Zoom during the quarantine.

It was that Saturday night. Everyone had CNN, MSNBC on in the background, and we never got to game-playing that day. It was the protest around George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. We just talked about what’s happening in the world. And watching the news footage, and from every city you would see, wow, okay, LA. Okay, Chicago, New York. There was a side comment like, “God, we should be doing the play right now.”

How can we be in this conversation? How can we use our art to really further propel this conversation? We saw that his book had resurfaced on every single reading list every single week, as people were at home, trying to process what is happening in the world. Between the World and Me just became another topic of conversation again. We really began exploring, well, how do we get this out?

Let’s remount this. Let’s do that now. We obviously can’t do the play. We obviously can’t gather people in the same room. Then we said, “Well, let’s make a film.”

The book and the theater production touched off a wider cultural conversation – like this panel with author Ta-Nehisi Coates and Black Panther stars Chadwick Boseman and Lupita Nyong’o at The Apollo Theater on February 27, 2018 in New York City. Photo by Shahar Azran/WireImage

Chapter 10: Back into the forest

KAMILAH FORBES: It was right back to that moment of like, “Oh my God, we sold this film to HBO,” to “Oh my God, I fucking sold a film to HBO, and now I got to make it.” What? I’ve never made a film before. I’ve never literally, you know, I’ve produced a bunch. But what? Wait a second, but you’ve been directing for 25 years, close to 30 years, you know this, you know how to do this. You know how to story-tell. But it was getting over that and getting that seed of confidence that you can do this.

This film was a real gift in 2020 for me. Because I know the fog and the forest of creative art-making. The fog and the forest of a pandemic I didn’t know. The bulk of my day was really concerned with survival, whether it was my own personal survival, my family’s survival, my husband’s survival, my daughter’s survival, keeping her home from school. Going out to the grocery store, it felt like, “Oh my gosh, please be safe.”

Survival of my institution. The doors are closed, what are we going to do? How do we make sure that our staff can survive? So when this opportunity came up, it almost felt like, yes, here we go. Now there’s an opportunity for me to get lost in the forest, for me to really start to swim in the water again, in a way that’s familiar, in a way that 2020 has not been familiar.

I remember calling Roger Ross Williams, right, who had shot the original opening night. And I was like, “Roger, can you partner with us to make this film?” He was like, “What film?” And before I can even finish, Roger was like, “I’m in, yes, I want to do it.” And then I was like, “Okay, so Roger, so I think we got to get this out in the next couple of months.”

Illustrator Kelsie Capitano created this image inspired by Kamilah Forbes’s story of walking into the forest.

Chapter 11: A film – in record time

How do you create within constraints? You use them to your advantage.

KAMILAH FORBES: Our deadline was in three months, and that was the deadline we put on ourselves, right? Because we wanted to make this an urgent opportunity. Didn’t want to wait a year. No.

We literally had to make a film in the most challenging of times when you cannot make a film in the traditional sense.

This is August of 2020 when there was barely anything being shot during that time. Casting was the easiest thing because everybody was free. What are they doing? They’re at home. And at the same time, so many people were eager to want to participate in something that was saying something important.

We couldn’t have actors together unmasked. The unions wouldn’t allow it. If we know we can’t pull actors together, how do we build sort of this creative nest?

I would fly in to talk to the actor and give notes. And my flying in was pretty comical because I was in full PPE. So I had an N95 mask on, I had a face guard. I had a surgical gown, as well as plastic gloves.

And in the background, once again, that’s my daughter.

Sometimes we were shooting in their actual homes, but with a very skeleton crew. The crew would set up without the actor being on site. And then either I, depending on the room size, was in the room with the actor or in an alternate room because our actors obviously were unmasked.

If we’re shooting just one person, I want it to be as tight as possible. It allowed us to get so intimate with each actor. Even just with our framing. I want it to feel like they were on the other side of the screen at all times. That you could reach out and touch them.

Our LA shoots and our San Francisco shoots, and our Atlanta shoots, I was on Zoom. And I could only see them based on what the camera was seeing. My DP was my eyes and ears. So at times I would have one earpod in, listening to what’s happening on screen through the camera, and another earpod in talking to either my producer or my DP directly to understand, tell me what else is happening in the room. What’s going on with the lighting? Can we widen? We had to over communicate in these situations, over plan. Because in the room where we would ultimately be there together, we didn’t have that luxury.

With the play, Ta-Nehisi didn’t see it until right before opening in our tech run-through. In this process, I also started sharing rough cuts with him so that he actually was seeing and providing comments and thoughts on the film as well. So his hand was very much a part of it.

We did have a conversation before we shared this piece of work with the rest of the world. We had a little Zoom actually with our original game night cohorts – we’ve now named ourselves FreeThe Land Collective, and it was almost like, are you ready? Are we ready? Are we going to share this?

Kamilah Forbes gives feedback to Marc Bamuthi Joseph during filming of HBO’s Between the World and Me. Photo: Lelanie Foster/HBO

Chapter 12: An audience outside the Apollo

How do you meet the expectations of millions? You tap the talent of every collaborator.

KAMILAH FORBES: Oh my goodness, the world now, there are so many eyes on this. This is not just 1,500 people that could get to your theater. These are people that could access in their homes around the globe. And that’s a very daunting feeling.

We are looking to weave a tapestry through all these disparate forms, voices from all these people from visuals from home videos to found footage, to archival footage, a visual tapestry of artists. One of the most impactful moments where the visual takes center stage is with the monologue, “It Had to Be Blood” to be able to not only have an iconic voice like Oprah illustrate what I believe Ta-Nehisi does in language but also to have this striking visual animation by an animator, Molly Crabapple, telling sort of this generational folklore of how we got here.

They have the opportunity for immediate conversation. So now, not only can I watch the work, but I can watch the work and talk about it while I’m watching it with other people from around the world who are also watching the work. This is what we wanted. Immediate conversation because of social media. That was the trippiest moment. But at the same time, this is exactly what we all set out to do.

Chapter 13: What this work means now

KAMILAH FORBES: Between The World And Me is an opportunity for liberation.

You know, what the work did emotionally was really allowing a space to mourn, you were being taken care of amongst the contextualization of Black beauty and Black joy and Black resilience, all at the same time. I think that in so many cases, we are not afforded that. We’re not afforded both spaces at once.

Police-sanctioned violence against Black bodies, there has been one after the other, after the other, after the other, where it’s almost like we can’t even hold our breath anymore. I can’t even hold my breath to the point where I can’t even release. I haven’t even gotten over the last moment in which there’s yet another.

In spite of all of that, along the way we have created a culture, a people that is so beautiful and joyous, and built American culture in a way that is unimaginable, has contributed to global culture in a way, in spite of, that is unimaginable. That we as a people are unstoppable. That’s what I mean by liberation. And in that journey, you find liberation.

I love this line: “This is not new to Black people. We’ve been here before.”

What I think that this work allows is just a brief moment to let it out.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Kamilah for sharing the story of her creative journey. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you found something in it you can bring to your work. Whether it’s the way she took that initial burst of creative energy — when she was alone in a hotel with the book — and channeled it into a campaign of patient persuasion with Ta-Nehisi. Or the way she cultivates community in her cast and crew — as a tool for building trust and inspiring their best work.

Maybe it’s the way Kamailah inspires each collaborator by giving them just the kernel of an idea and the space to create around it. Or maybe it’s the way she embraces fear at the beginning of a creative journey — but keeps collaborators close as she feels her way through the forest.

Joe Morton reads a passage from “Between The World and Me” at the Apollo Theater. Photo: Shahar Azran