Turn crisis into art

When faced with a crisis, how do you move forward? Sometimes, you look backward first. It’s March 2020, and legendary choreographer Bill T. Jones is weeks away from a world premiere, when his company is forced into lockdown. All seems lost. But what comes next paves the way for a transcendent performance at the Park Avenue Armory called “Afterwardsness” — one of the only large-scale performances held anywhere during the pandemic. On Spark & Fire, the larger-than-life Bill T. Jones tells this powerful story of creative grit, love of art and reckoning with legacy — in his own fierce, fiery, funny words. He’s joined at times by his Associate Artistic Director, Janet Wong, and together they offer inspiration and ideas to fuel your own creative journey.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: The gods are against me

- Chapter 2: Facing the unknown

- Chapter 3: We can get around it

- Chapter 4: My first partner, confidante, and conspirator

- Chapter 5: When the rehearsal room is your living room

- Chapter 6: The work is no longer yours

- Chapter 7: The reckoning

- Chapter 8: A new work emerges

- Chapter 9: The constraints of Covid

- Chapter 10: Give them agency

- Chapter 11: Opening night

- Chapter 12: What the audience sees and hears

- Chapter 13: You decide what it is

- Chapter 14: Back into the wilderness

Transcript:

Turn crisis into art

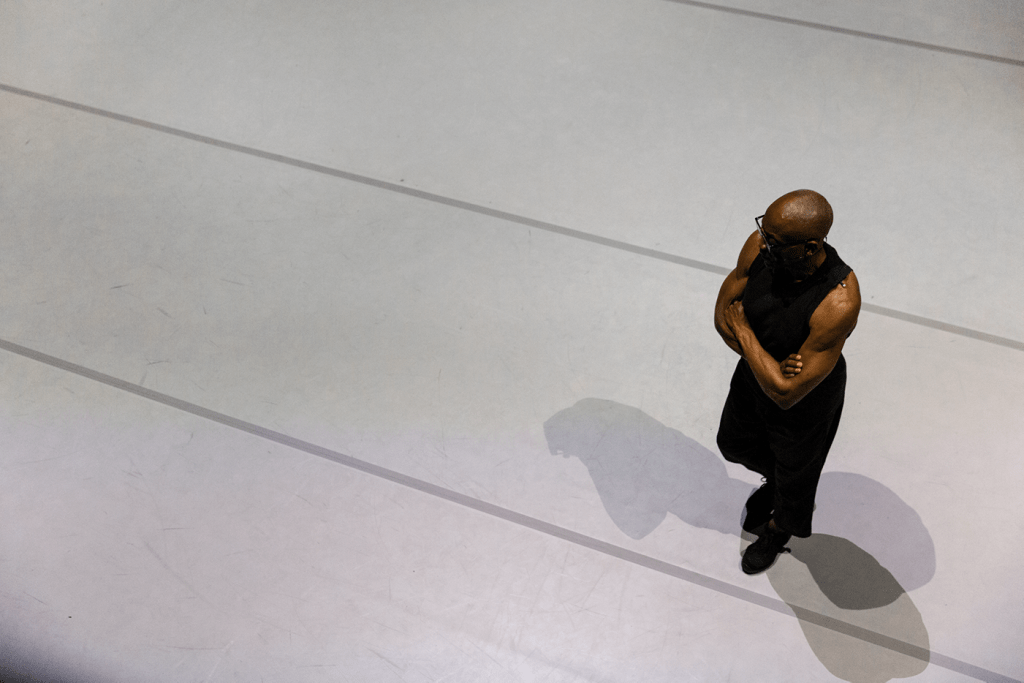

In the beginning of 2020, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company was developing a major new work: Deep Blue Sea, based on the story of Pip, the cabin boy in Moby-Dick. In the middle of rehearsals at MASS MoCA, the pandemic struck. Photographed by Maria Baranova.

Chapter 1: The gods are against me

BILL T. JONES: I wasn’t hearing those words, pandemic. What are you talking about? I lived through the AIDS crisis!

I think I was holding hope against hope that maybe we’d go home for two weeks. I think I didn’t want to know. All you can hear is, “My work is threatened.”

My mother, Estella Jones, she used to sometimes say, “I just feel like I could scream,” and she would. Estella would. It was a frightening and beautiful scream. Bill T. Jones feels like he could scream, “The gods are against me. Is there something we can do about this? Surely there’s something we can do. Surely somebody is responsible.”

JUNE COHEN: That’s Bill T. Jones. Legendary choreographer. Larger-than-life personality. Thinker. Performer. Provocateur.

And Bill’s about to tell us the story of creating the performance called “Afterwardsness.” It was one of the only large-scale performances held anywhere during the pandemic. It followed strict social-distancing guidelines, which isn’t easy in dance, where performers normally partner with each other. But it used those constraints as a springboard to create something entirely new.

Before we hear that story though, there are a few things you need to know. First, when the pandemic hit, Bill T. Jones was in final rehearsals for a different landmark piece. It had a cast of more than 100 dancers; it was the first time in years where Bill himself planned to perform publicly. It was called off just weeks before opening night.

And that’s where our story starts.

It’s a very specific story about a legendary, avant-garde choreographer responding to the existential crisis of the pandemic. But it’s also a deeply universal story about the way crisis and conflict are the kindling for great creative works.

Here are a few more things you should know about Bill T. Jones. Like: the sweeping arc of his career. For nearly 50 years, he’s pushed the boundaries of dance. In the 1970s, he and his partner Arnie Zane were known for their unconventional duets. Their company thrives to this day, creating landmark avant-garde pieces. And Bill has also taken home two Tony Awards for his Broadway shows. His company’s associate artistic director is Janet Wong, and we’ll hear from her too.

The original music you hear is our composer Hil Jaeger, who’s playing along with the story. For some wonderful, historical visuals while you’re listening, go to: sparkandfire.com/billtjones

[Theme music]

Rehearsing in a space at MASS MoCA, the production of Deep Blue Sea pulled in many collaborators across disciplines from music to architecture. When lockdown came, the ambitious new production became impossible, and dancers were sent home. Photo courtesy of Kaelen Burkett.

Chapter 2: Facing the unknown

BILL T. JONES: We were in deep research and development, technical mode for a piece called “Deep Blue Sea.” One of my dancers said his roommates had been exposed, so to be safe, he couldn’t come to rehearsal. He was rooming with our stage manager, and then she was not able to come to rehearsal. Another dancer was having real serious psychological responses to this. He was saying, “I have to go back to New York.” I said, “What?” He’s telling me, “I’m leaving the project. I’m a danger to me, and I’m a danger to you.”

I remember being shell-shocked when we had to close up shop and go back home. We didn’t know when we’d be able to be together again, we didn’t know what the future of that work, “Deep Blue Sea,” would be again, and I didn’t know when I was even going to see my dancers again. The city was emptying out except for the people who could not leave, and what’s going to happen? That was this painful moment of putting away one dream and facing the unknown.

As rehearsal ended, Bill wondered: “Would I ever see my dancers again?” Photo courtesy of Kaelen Burkett.

Chapter 3: We can get around it

When faced with a crisis, how do you move forward? Sometimes, you look backward first.

JONES: So I’m thinking, oh my God, well, if we’re not in the studio every day, what are we doing? Who is responsible when people’s gigs are canceled? Who is responsible when all the dancers are told, “Oops, sorry, that project’s just not happening.”

Yet it breaks my heart when I see someone who comes in there with a fire, or more impolitely said, the piss and vinegar, that young artists need. And this art form means pushing back against the patriarchy, against capitalism, against inauthenticity. Then when you see them learning that you might have those ideals, but the way the structure is set up, it’s not going to be there to support you.

Many of them literally are couch diving. When something like this Covid comes along, when things are being canceled left and right, it points up the weakness in our system. Are people’s lives stable? Can I keep them employed?

Now, of course, while Bill is thinking that, licking his wounds and screaming at the gods, my associate director, Janet Wong, my heart, my right hand, she’s one of our greatest weapons, she’s just thinking, hmm, I know that’s this is happening, but we can get around it.

Janet Wong, associate artistic director of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. Photo courtesy of Eric Politzer.

JANET WONG: We decided to have weekly meetings, Zoom meetings with our dancers. We didn’t really want to rehearse. Instead, I went into the archives and dug out these old phrases. A phrase would be the movement sentence. It’s chaining a series of movements and gestures together to become a phrase. So you can rearrange the phrase, you can do it backwards and forwards. You can do it in slow motion.

BILL T. JONES: We could go through all the repertory and find solos, go back to something when Bill was really on his legs and spending hours in the studio fashioning phrases.

There’s the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane grappling, early 1980s work. Then there are the works like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which were big splashy things that got a lot of people very exercised in the era of Jesse Helms and Robert Mapplethorpe. Then there was “Still/Here,” that very important, but very troubled work that it was.

JANET WONG: Through those phrases, you also learn about the history, where that phrase came from. Where was Bill when he made it? What was he thinking?

BILL T. JONES: And it was a kind of an interesting retrospective. They were being invited to look at old repertory, and that was very, very disconcerting. I forget how young they are. I wasn’t sure, from early conversations, if they even liked them. I don’t think some of them had ever seen works like repetitions, odd grappling, very few ta-da moments, very not playing to an audience, whatever Arnie Zane and I were doing.

BTJ/AZ rehearsal on Zoom with, clockwise from top left, company member Huiwang Zhang, associate artistic director Janet Wong, choreographer Bill T. Jones, and company member Vinson Fraley. Photo courtesy of Janet Wong.

Chapter 4: My first partner, confidante, and conspirator

BILL T. JONES: Arnold Martin Zane, at one point he would have been called androgynous or effeminate, now we would say gender-nonconforming. He was fierce, and he taught me something about fierceness. I met him when he had just returned from Amsterdam, Holland, and he looked like no one I was surrounded with. It was in the early ’70s, everyone was shaggy, kind of Crosby Stills and Nash-ish, and he came back with close-cropped hair, wearing an antique Dutch hand-knitted sweater, jeans that had glitter sewn up the sides. He was doing what they called at that time, genderfuck. David Bowie, and here I am, this kind of proto wannabe Jimi Hendrix, who he found very attractive and kind of amusing, my naivete.

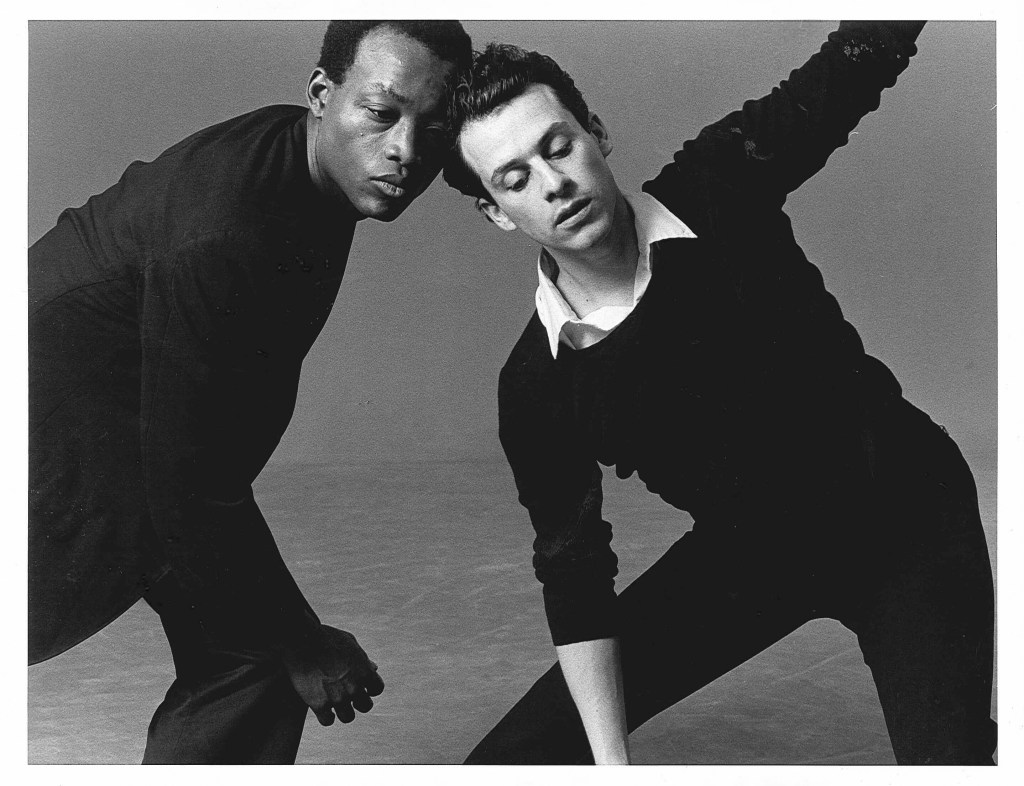

Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane. Photo courtesy of Lois Greenfield.

He and I had been making duets since about 1978, ’79. We formed the company in 1982. What does it mean when a white man, smaller white man, is onstage with a Black man? Arnie was five-foot-four, feisty. I am a six-foot-one. I’m brown skinned. I have an athlete’s build. What does it mean when the large person, the Black man, is holding his hand out, and this small Jewish/Italian man is taking him and walking him in a circle as if they were doing the, what’s it called?, the Rose pas de deux or what have you, Sleeping Beauty? It was tongue-in-cheek, but it was also about upsetting, upending the notion of power. That was a hallmark of what we were about.

We fought like hell. It was almost choreographed into the duets we made. Sometimes there’s this conflict, which could be Mutt and Jeff, slapstick that could turn really shockingly violent. But then it was also extremely tender.

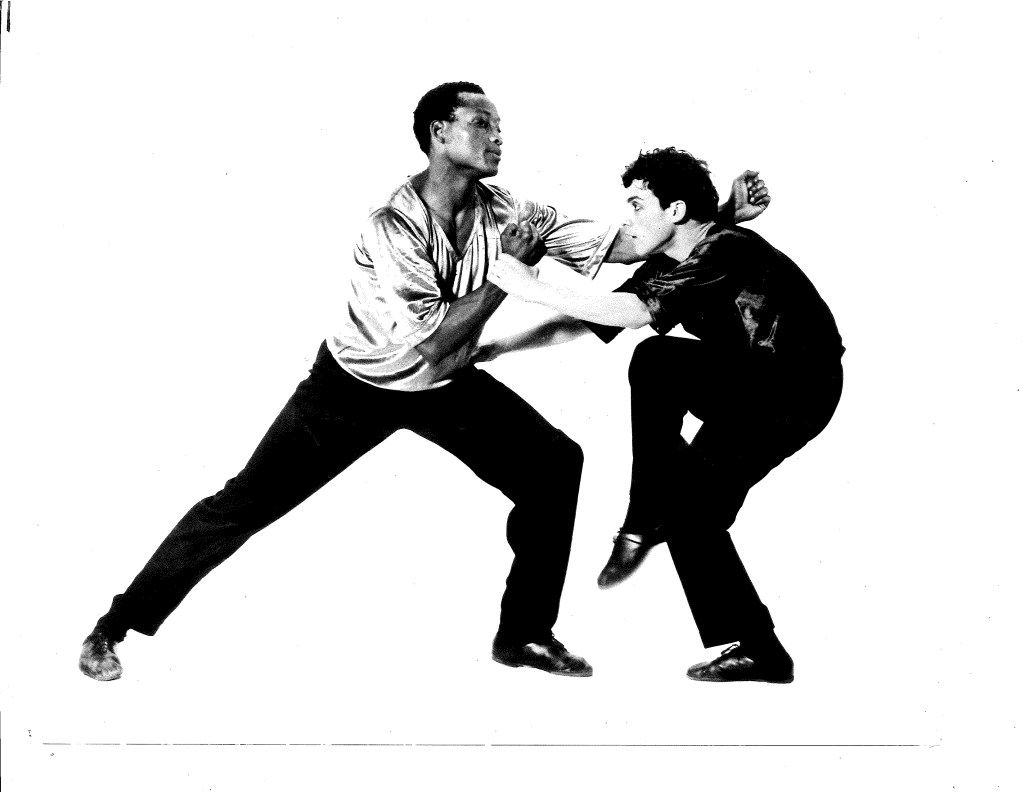

Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane. Photo courtesy of Tom Caravaglia.

At the end of Blauvelt, there’s this whole sequence with benches. Toss one bench into the wing, toss the second bench into the wing, and then Bill runs, tosses himself at Arnie. I must’ve outweighed him by at least 60 pounds, if not more, and Arnie underneath. The end picture of me up, suspended, and blackout. Now, of course, in the dark, we would collapse, and matter of fact, it even hurt his back, but he insisted he wanted the world to know that he was not weak. He was strong.

He was one of the first people in the art world to come out and talk honestly about AIDS and the arts on The MacNeil/Lehrer Report. He actually allowed them to come to our house and interview him. He had an IV drip in his arm because he was doing one of the many therapies that people were trying at that time.

He died in this very room that I’m in right now, in March of 1988. He loved me dearly. This romance was real. With that was also an intimacy in the life that we were sharing together. Life was a great adventure we would run out to meet. He was my partner, confidant, conspirator, and the king of my heart.

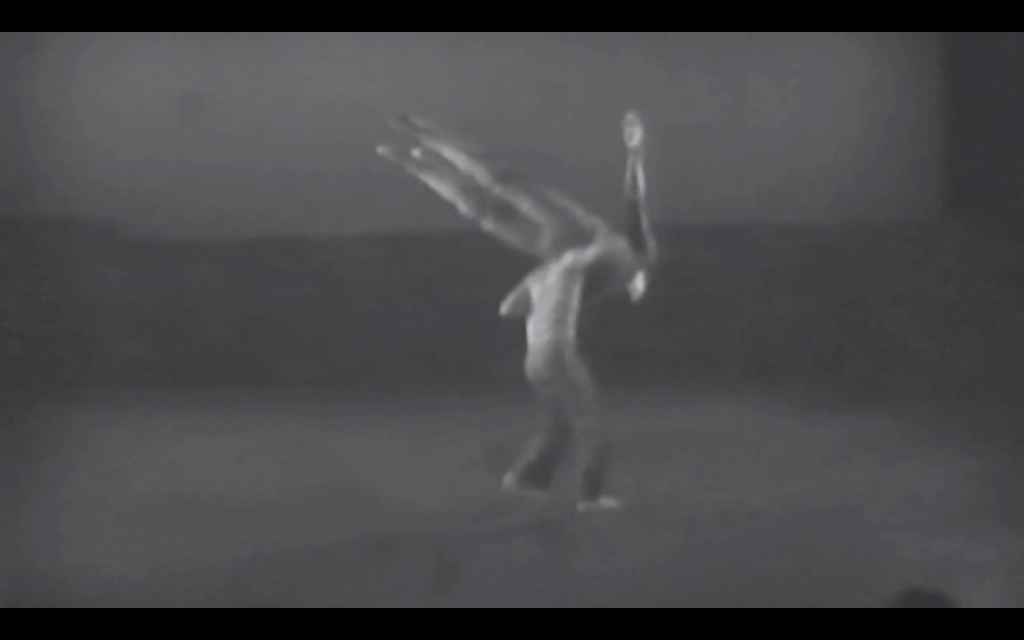

From an early performance of Blauvelt Mountain, with dancers Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane. Watch clips from Blauvelt Mountain.

Chapter 5: When the rehearsal room is your living room

BILL T. JONES: Is it really time to take a breath, reconsider, re-approach? We’re trying to give people time to learn a critical mass of these phrases in their little domiciles. Then we would set up coaching sessions.

JANET WONG: In the very beginning, it felt like it was busywork. We just want to keep the dancers engaged. We don’t really know what we’re doing.

They all have to learn the material, and then videotape themselves, and then send it to us. This material is challenging. It’s hard. This being on Zoom is not friendly to the body.

One of the dancers, Shane Larson, he did everything on the rooftop. I would be worried that he’s tripping on something because it’s not dance-friendly, but somehow he managed.

BILL T. JONES: Huiwang, he has taped out very precisely a 10-by-10 area, and every once in a while, his little daughter would walk through it, looking at the camera like this. But Daddy is doing this phrase, doing this phrase material.

JANET WONG: She would pop into the video once in a while and just stare at us, and our hearts would melt.

Dancer Huiwang Zhang taped out a 10×10 square for dedicated rehearsal in his small living space. His daughter would wander in and smile at the camera. Watch this clip.

BILL T. JONES: Vinson Fraley, he’s doing one of the phrases in a field. I can’t even see, what the hell is he doing out there?

Dancer Vinson Fraley found rehearsal space outdoors in a clearing among trees. Watch this clip.

Then there becomes the dicey thing, okay, everybody can’t learn everything, so you have to choose these particular dancers. This movement would suit them best. Is that fair? Or, this particular dancer has this quality that Arnie Zane had in his body, maybe they should be given this. Well, any way you cut it, you always run the risk of discounting someone’s ability to stretch or even fold in, but we did it, and we gave out the material. I think we made the right choices.

JANEt WONG: Sometimes those old videos, it’s hard to see what Bill is doing. And it’s a skill to learn his intention as well as learn the movement.

Sometimes, you just see a lot of movement happening in the lower part of the body, but actually it’s initiated from the top of the body, and you have to go inside his head and listen to that intention.

Just seeing all of them do these phrases … Some of them have only been performed by Bill himself.

BILL T. JONES: I hadn’t really looked at the tapes. I don’t want to look at myself doing them, but then when I look at them doing it, I thought, “Oh, that’s that phrase I struggled with for so many weeks to do. And now they’re doing it. Oh no, no. That is wrong. No, no, no, no. The leg should be 90 degrees.” But when I look at myself doing it later, “Your leg wasn’t 90 degrees, your leg was 45 degrees. You felt it at 90 degrees.”

But that’s how we began to get our vocabulary, retrospectively.

JANET WONG: By the third session or so, Bill was saying, “Okay, this is going to be the beginning of a new work. When we come out of this, we’re going to put all of these phrases that you’re all learning together and create a work. And that will be about this moment in time.”

COHEN: After the break a moment of truth and holy fire.

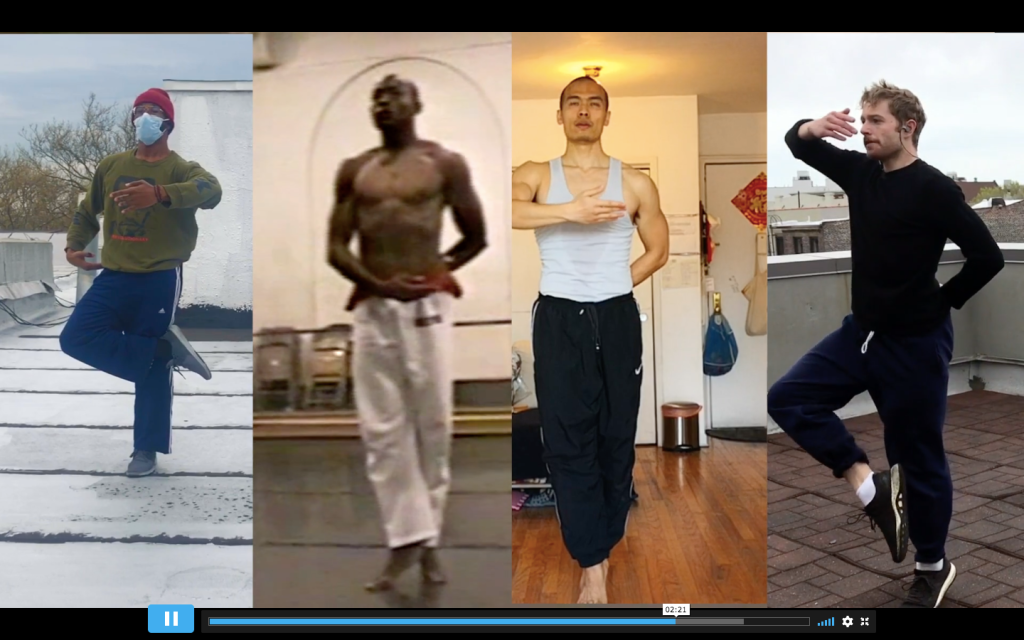

Four dancers interpret a phrase from “Rumi,” with, from left, dancers J. Bouey, Bill T. Jones, Huiwang Zhang, and Shane Larson. Watch this absolutely mesmerizing video clip.

Chapter 6: The work is no longer yours

How do you train the next generation? With holy fire.

BILL T. JONES: Now I can tell them, I want them to do this thing. Imagine both arms come up at 45 degrees from your shoulders, the fingertips curl down, and they come into your sternum, and you collapse in, as if saying, “Oh, baby.” Now, that’s what I was doing. But I wasn’t thinking. I was just feeling it. Now these young people, do they understand what you mean, “Oh baby”? They’re giving me the shapes they see on the tape, but do they have to have Bill T. Jones’ inner life to do the movement? Now, how do you explain that in a Zoom call? You can use words like that, but then what they hear is: “Bill doesn’t approve. And why is he always so critical?”

In the golden age of contemporary dance, the choreographers were these kinds of gurus young people would come to for direction and advice, philosophy and so on. If you think of Martha Graham making some of her most important works in the ‘30s, she was able to be like a guru goddess. You worked with Martha, you didn’t work with Doris Humphrey or José Limón.

And that was one of those things that also took me a while to understand through Covid, that you ain’t got that nurturing thing, man. “Yes, dear. That was really wonderful. Come over here, and let me give you a squeeze and encourage you to go forward. And then you’ll just do it a little different next time.” No. No, that’s not my strong suit. I’ve been called the 800-pound gorilla. And sometimes I behave like a bully. And just the way I express myself, it feels confrontational. And what do you think?

There’s a fire burning my ass at the moment, and it’s going to burn yours too. Because that’s the holy fire that makes for people who are artists and people who are not artists. And this is the moment of truth, when you’re making that transition, and your work is going into its third, fourth generation of bodies. What is the real version? It’s no longer yours, Bill.

Bill T. Jones in a dance workshop at the Mann Center. Photo courtesy of Mike Oswald Photography.

Chapter 7: The reckoning

What happens when the whole world convulses? Everything has to change, including you.

BILL T. JONES: I believe it’s Yeats who said it. “Art making happens when something is being pushed against.” Artists have an embattled relationship to the world, a world that is constantly telling them what they should and should not do. Art is often a form of rebellion. Many great works of art happen because of those forces of psychology that threaten to cut off our voice, and art is a muscular assertion that I am here, and I do speak.

Chanel Howard called and said, “With everything going on in the world, I can’t be on this call.” The night before, George Floyd had died on camera. And she was, as a young Black woman, woke Black woman, “You want me to come on a call and do modern dance coaching? Now, here we have a little dissonance, don’t we?”

“This is your job, honey.”

“I know, but this is a bigger time than even this job.”

I was really pissed. We had words.

There was one performer in particular: “The dance world, the art world, are all products of this white supremacists’ patriarchal system, and we should not be part of it.”

Wait a minute, hold on. “Aren’t you expecting your check at the end of this week? Does it matter that these rich white people on my board are paying?”

“Well, we’re thinking about the future. We’re thinking about what we should be doing, and you, Bill T. Jones, you should use your privileged position to be doing this. If you’re not part of the solution, then you’re part of the problem.”

This was not said overtly, but that was coming out of things, comments that were being said. And if you want to insult an old rebel, tell them they’re no longer a rebel. Oh boy. “Are you saying that I am the oppressor now?”

“Oh, you raise your voice at people. You have power over people. Yeah, you are part of the problem.”

Oh my God, have we come to this? Arnie, help me out here. Remember when we used to be the vermin that they allowed in? And when we got our first grant, we thought we’d gotten away with something, because after all, we ain’t got no technique, we ain’t got no repertory, we ain’t got no reason for being here. By pure force of will and wile, we had made our way into the door, but we expected any day now, they’re going to get out the exterminator, and get rid of the likes of us.

I wanted to run away.

Dancer Chanel Howard questioned the idea of running rehearsals in the middle of 2020’s summer of social unrest. “We had words,” says Bill now. Her conversation helped push the company to a deeper engagement with the moment.

Chapter 8: A new work emerges

BILL T. JONES: At the time when all theaters are closed down and everyone is wondering about how we’ll pay artists, where we will be in six months. The phone rings, and somebody says, “Well, would you like to consider making a new work?”

JANET WONG: Around June, Michael Lonergan, producer of the Armory, he would like to offer us a commission for a socially-distanced work.

BILL T. JONES: They said, “We’d like you to make a piece.”

“Are you kidding? What about the last one I’m making?”

“Well, we can’t do that right now, but would you like to make a piece that is going to help us do a thawing, a thawing of their presenting? And it shouldn’t be terribly expensive. We shouldn’t need a lot of bells and whistles. And it should be a very small audience.”

I said something kind of bravura: “We can do it. If you give me 10 days in a space, we’ll give you a piece.” And you know what? We did.

JANET WONG: During the summer, we had a site visit at the Armory. We’d been there many times, of course, but just to imagine the Armory for this purpose and just to see what they’re talking about when they say, “Oh, the audience will be seated 11 feet apart.”

BILL T. JONES: “We’re not trying to sell tickets to this.” Well, that was good to hear. It means you can have that beautiful room just for pure inquiry.

JANET WONG: The raw space is beautiful, and it’s huge. It’s so huge. Bill, right away, said, “We’re going to make a piece with all the phrases that the dancers have been learning.” He said he was so taken by the dancers, rehearsing and moving and dancing in their little rooms, he wanted to carry that idea to the piece.

At the Armory, the company found enough space to move, safely, through the patterns of the dance. Photo courtesy of Bjorn Amelan.

Chapter 9: The constraints of Covid

JANET WONG: That first day of rehearsal, they were doing this simple walking pattern. They’re just walking around the space. And Bill and I were like, “Oh my God, it’s so beautiful.” Literally, we had not seen humans walking in that way for so long, that the simplest thing they do was so beautiful and amazing. That feeling carried through the next so many weeks of rehearsing.

BILL T. JONES: In “Afterwardsness,” I think you have a group ensemble that suggests something of dependence and communality. That is what partnering traditionally would have done.

JANET WONG: The company’s known for partnering. And Bill and Arnie started off as a duet team, right? The restrictions, not being able to partner. There’s no holding hands. There’s no putting your hand on someone’s back. None of that. At one point, we were … Bill wanted people to do patty-cake, the children’s game, and then we’d realize, “Oh, we can’t do that. No touching.” So, they did it apart.

BILL T. JONES: There were rules. The rules of the space. Who could go where. Those rules are also choreographic, ultimately. Dancers should be careful not to be so close to each other that they’re breathing on each other. That means that there’s a certain way in which the choreography is like gaseous clouds avoiding, curling around each other, and wonderful intention across great space, the intention to be “in unison” with somebody who is 60 feet away. And there’s, between you, a bank of human beings.

JANET WONG: I always think that obstacles and limitations just allow us to think differently and create things that you would never create under normal circumstances.

Chapter 10: Give them agency

How do you breathe life into a performance? You leave some questions unanswered.

JANET WONG: The room was charged with people who really want to work, who really had something to say at this moment.

The dancers have a lot of freedom. They make a lot of their own choices. A lot of it is set and choreographed, but they have a lot of choices and decisions to make. I think that also allowed them to own the work. They are part of the making of this piece. And it’s made there and then in the moment.

BILL T. JONES: Janet and I, through this mysterious process of making sequences, how you get from one sequence, transitioning into another sequence, and what will be the music in the air, and when will there be vocalizations. The choreography, in a way, makes itself through those task-based instructions.

At this moment, you need to be here. And using your imagination, any way you want, you must locomote to another point in time. You’re looking at this like a chess board. As it moves around, where do you think it needs to be heavier or lighter in terms of bodies? What do you think? There’s a time to stand still. They’re making these decisions in the moment. I think it was charged because you could feel the dancers really striving to psychically connect across space.

Give clear instructions, and look for unexpected answers to them. You give them agency. They make choices. They can choose to jump in and jump out.

Agency. That word is very important in making work like we make. How can people be given agency? Or how tolerant am I to people taking agency?

Chapter 11: Opening night

BILL T. JONES: You arrive in front of the Armory. You have had your Covid test. You have your temperature taken. And then you’re assigned to one of the four beautiful rooms there.

JANET WONG: They had set up chairs in the Tiffany rooms and in the hallway. They all had that soundscape that Shane created. Shane had been going to protests, every protest, every day, and he was doing a lot of field recordings.

BILL T. JONES: You hear what sounds like a documentary of people talking about their experience, isolated. Routines. Mealtime. Some people went home to their parents, and they have very conservative parents, but then you hear someone talking about, at the end of the evening, they’d go to bed, and his husband turns on his side, and he, my dancer, reaches over and massages his head and puts him to sleep. Deep human stuff in a political environment.

JANET WONG: That soundscape brought up so much expected and unexpected emotion.

BILL T. JONES: People are wondering, “What’s this going to be?” And then one by one…

JANET WONG: They will lead one room at a time into the Armory. You are led in, everyone’s en masse, in single file. It’s like kindergarten. It’s so fascistic. Art shouldn’t be that way. Well, this is the poetics of the moment. And it takes forever. I think the first night, it must’ve been almost 40 minutes.

And it was amazing how silent everyone was. They had somehow signed this silent agreement to be patient. So patient.

BILL T. JONES: Nobody’s talking, like at the doctor’s office. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? Well, it’s the thing we got right now.

JANET WONG: There was a heightened sense of something special.

BILL T. JONES: The care we all had about being socially distanced. We’re all in masks. We’re finally in. And I’m thinking, “Oh God, I hope they can get enough people.” One hundred people is … Everyone had to be vetted and so on, but it had to have a fullness to it.

JANET WONG: At a certain point, the musicians would take their places.

As the audience arrived, they were led to widely spaced chairs on the floor of the Armory. The blue tape on the floor indicates the paths the dancers can take through the space. Photo courtesy of Bjorn Amelan.

Chapter 12: What the audience sees and hears

BILL T. JONES: Suddenly, the back door opens, and all the dancers rush on, banging pots and pans. You would have to have lived through Covid to understand the significance of what used to be called the Covid support for the first line defenders, but now it’s something else. Then you hear what Mark Gray did. I said I wanted a siren, something that arrests everybody. It sounds like a human, it’s very monstrous in a way, m-whoa, and suddenly we’re plunged into darkness.

Paul Wunjan, beautiful clarinet virtuoso, he starts playing these plaintive, sustained notes, just made for the cavern of the Armory. It’s actually the opening lines of the Abyss of the Birds from Messiaen’s masterpiece from 1945, The Quartet for the End of Time. All eyes were on him, and then suddenly, while you’re sitting there in the dark, somebody walks by you. They’re just walking at first, but the walking stops being just walking, and they’re allowed to do any locomotion.

Suddenly people are showing me everything they know from Paul Taylor side jumps, Merce Cunningham triplets, sexy walk, all those things, running. They have begun doing what we call The Clock. They were given the instructions to use the room and make a pattern that they were going to repeat several times.

JANET WONG: You can’t see everything all at once. There are things happening in multiple locations on purpose. You can pay attention to the person that’s close to you, or you can look far into the distance and see there’s also something else going on.

BILL T. JONES: Then they will hear a date, March 15th. They have to stop where they are, and we began the phrase. You begin almost to see a catalog of human movement punctuated by another date, March 30th, and they stop, and they do a bit more of the phrase. You have the agency. You can either stop and go back to walking, or you have to hold that. You, as the audience, are watching that small Filipino woman move past you, and then this large African-American man, and then this blonde Shane Larson, and then Wei Wong, and they’re all doing the phrases. They were behind you before, but now they’re across the room, 60 feet away, and it goes and goes and goes.

JANET WONG: The dancers were also in shock. “Oh my God, I looked over there, and I was looking at someone’s eyes.” One of the dancers, he said, “When I came into my little area to dance, Bill was right there.” Oh my God. Don’t look at Bill. Don’t look at Bill.

BILL T. JONES: Then suddenly there’s a quartet on the middle of the room. Still the Messiaen is going, and it’s very spooky. It takes you back to that rainy September afternoon in the prisoner of war camp when he premiered this work for 300 people, many of them prisoners, others guards. He is working with cracked instruments, instruments missing strings, and now those four people have squared off in an area in the center of the space that is a proper performing area.

They’re doing Arnie Zane’s material from 1981, this heel toe, heel toe, slap, slap, into the floor. Suddenly I thought, “Arnie, can you see this? This work is not dead. Your odd gestures now have new spirits enlivening them.” Messiaen drops out, and you hear one person banging on a pot. Then it breaks into a jam, and they are stomping, and it builds and builds and builds and stops. The room is dropped into silence. That’s when you hear Vinson singing.

In this illustration, artist Kelsie Capitano was inspired by the idea of the dancers moving through the Armory space, aware of one another but unable to touch.

Chapter 13: You decide what it is

What happens when your work meets the audience? It’s entirely up to them.

BILL T. JONES: “Another man done gone, another man done gone from the county farm, another man done gone, and another man done gone. They killed another man. I never knew his name. He had a long chain on.”

Other dancers have been distributed around the space, on their backs, in ghastly shapes as if someone were standing on your neck, or that you were sleeping dead, what have you.

We were listening to a violin playing by a Korean-American woman for eight minutes and 46 seconds, because that was the time that it took for George Floyd to die, and therefore that time became sacrosanct. I wanted the whole room to know that they were literally in the same space that George Floyd had had his last moments in, and the music was undeniable.

The dancers are strewn around the space, and they’re all lying in areas of light. You see Chanel almost like a neolithic goddess moving across a landscape. We didn’t have programs that outlined that this was called “Eight Minutes and 46 Seconds, an Homage to George Floyd.” You ask me what would I want them to feel? I’d want them to think, “What is going on here? Why is this happening, and why is it taking so long?” I had wanted them to know what it was, but others say, “Don’t you think they get it?” The woman said to me, “Oh, it was about all the dead people, the dead Black men who were killed.” I said, “Well, maybe it was just dancers during Covid dreaming in their rooms separated.”

You have to decide what it is. What does it mean? Martha Graham used to say, “If I knew what it means, I wouldn’t dance about it.” Was it just “pure abstract art,” or was it pointing to something else? I think it was pointing to your head and your heart, each individual.

JANET WONG: At the end of the piece, we didn’t go to blackout. We didn’t take a formal bow, but each dancer would go to the people near them and say, “Thank you for being here,” quietly to them. It was grand and intimate at the same time.

BILL T. JONES: There comes a moment after the third performance of “Afterwardsness” when she and I indulge in, just in passing:

“Well, Ms. Wong.”

“Yes. Mr. Jones.”

“I think we did good work.”

“I think we did.”

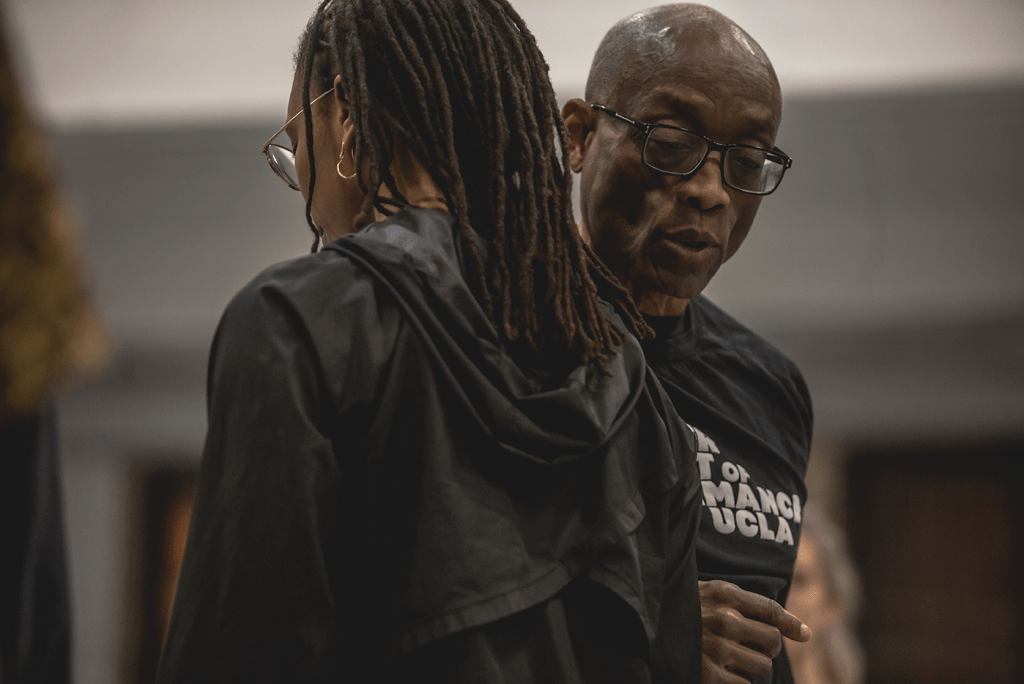

Bill T. Jones and Janet Wong at work together. Photo courtesy of Toshiko Oiwa.

Chapter 14: Back into the wilderness

BILL T. JONES: It’s communal. It’s frightening. It’s about how divided we are. “Afterwardsness” is about the sublime, and I borrow this from the Transcendentalists: “The sublime is all verging on terror.” It helped me, I began to believe again in the communal nature.

What does it mean to really have a community again, Bill? It means a new lease on a creative life. Yeah, that’s what “Afterwardsness” is. Can I follow it with something? Was this a one-off, Bill? Are you going to go back into the wilderness of disconnectedness from the public, your angry self saying “fuck you” through your work, or do you have a way to embrace who you are? You’re a multi-racial company. You’re a Black man. You’re not getting younger. People are not here to stay. Are you able to take all those things and lead it into something that moves people? Is that important again to you, Bill T. Jones, that things be moving?

I’m feeling fierce and brave right now. Always full of doubt, but “Afterwardsness” says, “It’s okay. It’s okay. You can do it, and the hearts and minds will be there.”

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Bill T. Jones for sharing the story of his creative journey. It meant so much to us to capture it and share it with you. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you got something from it, that you can bring to your own work, whatever your field.

Whether it’s the way Bill T. Jones’ work is driven by holy fire, as he says. Or the way he reckons with his own legacy as a leader, a rebel, and an artist.

Maybe it’s the soulful, seamless collaboration between Bill T. Jones and Janet Wong. Or maybe it’s just the way this gorgeous once-in-a lifetime performance grew out of the raw materials of conflict and chaos at this moment in time.

About the Creators and Host