How to find inspiration

What do you do when you’re stuck? Something else. Designer Chip Kidd got a dream assignment: Create the book cover for a soon-to-be-blockbuster: Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park. Oh, and make it iconic. When the pressure to perform is that high, it’s easy to get creatively paralyzed. Chip recounts exactly how he got started and how he got unstuck — over and over — on the journey to create one of the best-known book covers of the 20th century. He tells the story in his own fast-paced, funny, pointed words, with lots of smart, actionable advice for anyone setting out on their own creative quest.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: The assignment

- Chapter 2: Telling stories around the campfire

- Chapter 3: Start with what you know

- Chapter 4: Hitting your head against the wall

- Chapter 5: The breakthrough

- Chapter 6: The art and craft of completing

- Chapter 7: The cover we send to Crichton

- Chapter 8: You can do better

- Chapter 9: The fax machine

- Chapter 10: Coming soon: Jurassic Park, the movie

- Chapter 11: What this means

- Chapter 12: From cover to cover

Transcript:

How to find inspiration

How do you create a design this iconic? Start by doing the crossword puzzle. Then take the subway a couple of stops to the museum. In short, says book designer Chip Kidd: get out of your own head.

Chapter 1: The assignment

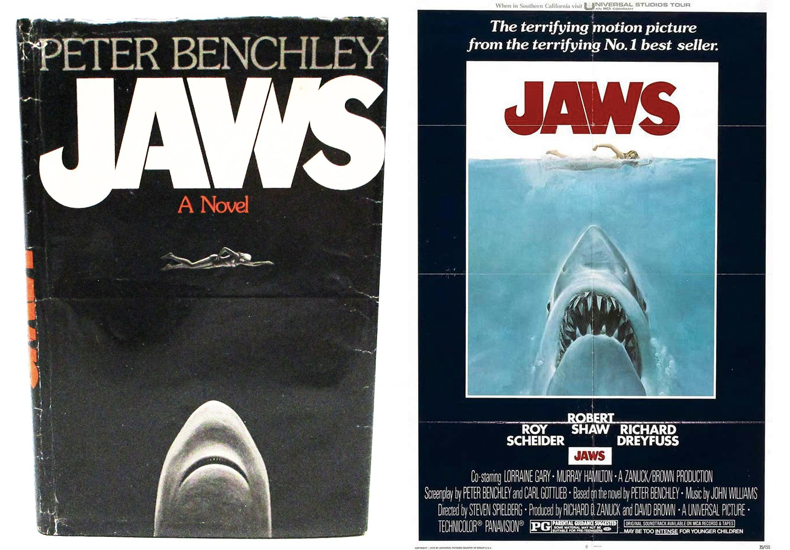

CHIP KIDD: My editor in chief, Sonny Mehta, said to me, “Think of ‘Jaws’.” I’m like, “Okay. You want to make something that’s going to be as iconic for this book as the movie poster ended up being for ‘Jaws’.” And I remember at the time thinking, “Right, like that’s ever going to happen. There’s no way in a million years that I am going to ever be able to do that.” So, you just put that thought out of your head, because if you’re trying to do something like that you’re bound to fail.

JUNE COHEN: That’s graphic designer Chip Kidd. He’s about to tell us the story of designing the book cover for Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton. You can probably picture the profile of the T. rex on that cover. It’s a design so iconic, you almost forget that someone designed it. But of course, someone did. And that was Chip Kidd.

And as Chip tells us the story of that creative journey, you’ll hear how he finds inspiration – again and again – by setting everything aside. Setting aside pressure, to begin with. But also his own assumptions, his first tries. and even the entire project. You’ll hear how Chip cycles through inspirations and ideas, what he does when he’s stuck, and how he goes in search of serendipity.

And here’s what you need to know about Chip Kidd. Today, he’s the world’s most celebrated book designer. Then, he was a junior designer at the Knopf Publishing House – and he didn’t know for sure that Jurassic Park would be a best-seller or that it would be adapted into a blockbuster film that pioneered the use of computer generated graphics. But he did know that expectations were high. And that’s where our story starts.

The original music you’ll hear is our composer Ryan Holladay, playing along with the story. For visuals while you’re listening, go to www.sparkandfire.com/chipkidd.

[Theme music]

At left, designer Paul Bacon’s cover for the hardcover edition of Jaws in 1974 for Doubleday. On the right, the original one-sheet poster from Jaws the movie, with poster artwork by Mick McGinty, who took inspiration from Bacon’s layout and typography. Book club edition of Jaws from Ken’s Book Cellar in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Movie poster image from 1stdibs.

Chapter 2: Telling stories around the campfire

CHIP KIDD: I was a young junior designer at the time, and I would have been about, what, 26? One by one, the editors tell you a story of all the books that they have on the list. I call it the corporate equivalent of telling stories around a campfire. Sonny Mehta, our editor in chief, he would always go last.

He just said, “This is a thriller from Michael Crichton in which scientists figure out a way to re-bioengineer dinosaurs into being, and let’s get excited. and let’s get started.” Spielberg had already bought it, he had already optioned it. Now, of course, movie people option books all the time and they may or may not get made, but we did know, from the beginning, that Spielberg optioned it.

Now a recognized master of the art of book design, Chip Kidd was a 26-year-old junior designer at Knopf when the assignment of a lifetime came his way: the cover of Michael Crichton’s soon-to-be-blockbuster book Jurassic Park.

Chapter 3: Start with what you know

What can you do if an idea isn’t working? Set it aside, and find the next one.

CHIP KIDD: We just started generating ideas. “What would dinosaur skin look like if it was very close up?” As in, you’re standing right next to it. And it didn’t look like anything. It basically looked like a sheet of bubbly leather, which is probably accurate.

You start with what we actually know. What do we actually know?

You’re dealing with a title that, at the time, nobody knew what that means. If the book was called Dinosaur World and then you show dinosaur skin, maybe that could work, but nobody knew what a “Jurassic” was at that point. So, you have a title that is abstract, and you put it with an image that’s abstract, and you get abstract squared, which in that case was not good. That was not working.

You needed something as a visual hook for the audience. Especially if the reader has no idea what they’re in for. It’s like, “Okay, I don’t know what a ‘Jurassic’ is, but look, that looks like it could be a dinosaur.” I’m starting to do the visual math in my head about what this actually means. What do we actually know?

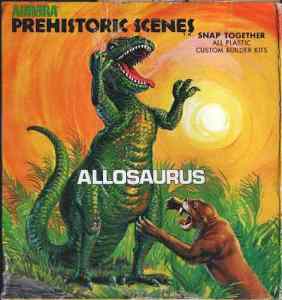

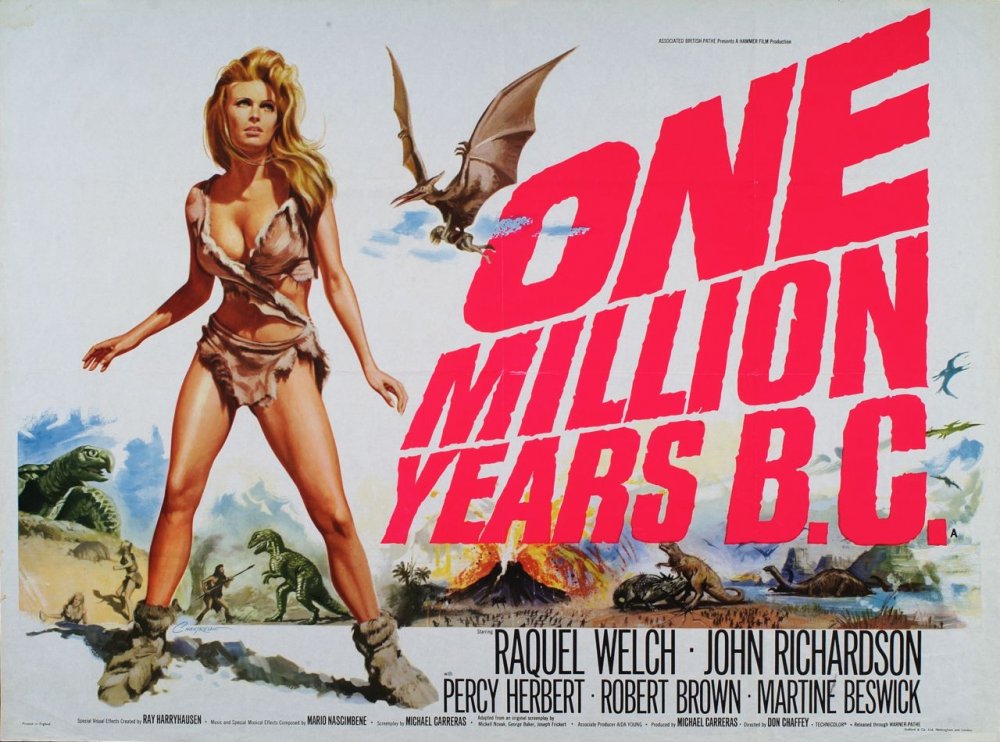

I was a huge fan of movies growing up, like “One Million Years B.C.” with the hokey stop-motion dinosaurs. I was a 1970s kid, and there were these model kits by a company called Aurora, and they did a whole line of dinosaurs. So I was totally into that, and I built them all, from the allosaurus and the stegosaurus.

I was so used to seeing that kind of imagery, say on the box lid of the model. I had a childhood template in my head of these toys, but therefore: Do something different. You don’t want to do something like that. I started trying different dinosaurs. I love a triceratops, I love a brontosaurus.

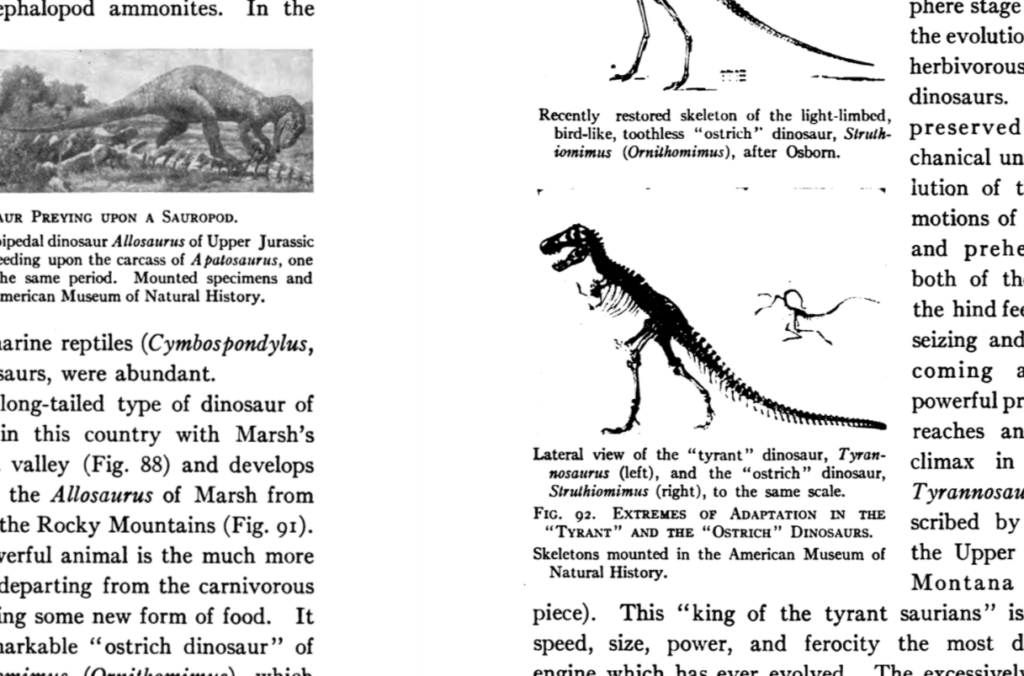

A 1971-era Aurora model of the Allosaurus, from collector Trevor Ylisaari, who maintains a site dedicated to Aurora models.

There was a scene in the book when all of a sudden they’re just being dive-bombed by pterodactyls, which is so great. So, I’m like, “All right, let’s try a pterodactyl!” Which I did. It was elegant, but it wasn’t scary in any way.

At this point, it’s been several weeks, perhaps a month. This is one of our most important titles on this list. We need to nail this sooner rather than later.

Most of the posters from the 1966 British-made fantasy adventure movie One Million Years B.C. feature a very large Raquel Welch, but the real stars of the film might have been the stop-motion dinosaurs designed by the legendary Ray Harryhausen. The British Film Institute collects his original drawings.

Chapter 4: Hitting your head against the wall

What do you do when you’re stuck? Something else.

CHIP KIDD: If you get stuck, if you’re hitting your head against the wall, you’ve been working on this particular project too long and concentrating on it, give yourself a break from it. Give yourself a break from it, and go do something else, because your subconscious is still going to be working on whatever it was that was giving you trouble.

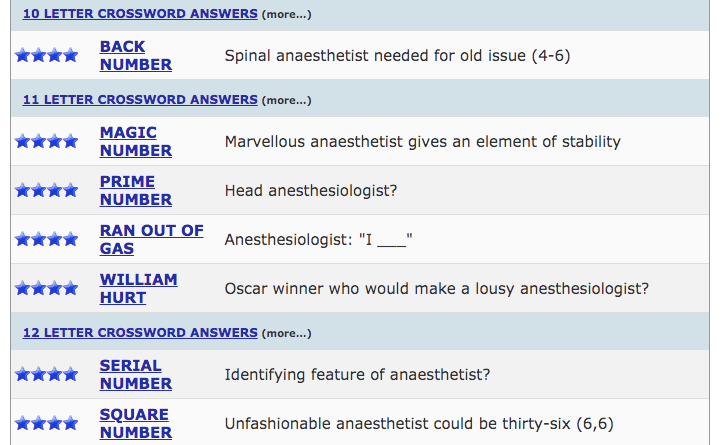

I love to do crossword puzzles because it helps me to think conceptually. My favorite example, the clue was – and I’m just going to spell it out for you. A N-U-M-B-E-R of people. Okay? A number of people. And the answer is ANAESTHESIA because it’s not a number of people, it is a numb-er of people.

And that to me is the magic of a really good crossword clue and answer, because it forces you to consider language in a different way. So, somehow that helps me to design book covers.

Crossword puzzle creators really do have a lot of fun.

Chapter 5: The breakthrough

How do you find an elusive idea? Go in search of serendipity.

CHIP KIDD: All of these depictions, both in pop culture and science books, I wanted to somehow get away from that and yet be true to what the thing actually was. And all roads lead to the Museum of Natural History.

I’m a big believer in serendipity. I’m not smart enough to have a clear plan in my head at that point, other than just to go there and see what happens. Out of the office building, get in the subway two blocks away, and take the transfer of the A train, like the song says, up to its own stop. And you get out, and you pay your entrance fee and in you go. And then there’s that faint, familiar smell from when you were a kid and you’re on a field trip. All of a sudden, you’re eight years old again.

Then you go into the dinosaur hall. Everything is marble: the benches, the floors, the walls, the ceiling. There’s nothing to absorb any of the sound. So you try not to make much noise, because whatever you say is going to be echoed around, and you don’t want to disturb the other people.

Specimen AMNH 5027, Tyrannosaurus rex, was discovered as a nearly complete skeleton at Big Dry Creek, Montana, by the famous fossil hunter Barnum Brown. It’s been a centerpiece at the American Museum of Natural History for more than a century. This 1960s-era image is more or less what the museum’s dinosaur hall looked like in 1989, when Chip Kidd stopped by. Photo courtesy American Museum of Natural History / 2007 METRO Project

Looking at all of the different dinosaur skeletons and bones and vitrines and big glass boxes, your imagination instantly gets put into fourth gear. And you’re trying to imagine what these things must have been like when they were alive. You’ve got all different kinds of animals represented, but the T. rex sort of commands the room. You can sit in a certain place where you can see the large open window behind it, so the daylight is pouring through.

I had a sketchbook. Back then you didn’t whip out your phone and take a picture of it, which is what I would do today, because that would be far better than anything that I could draw.

It’s backlit, and either subconsciously or consciously, you realize you’re not just looking at a dinosaur skeleton. You’re looking at a silhouette of a dinosaur skeleton. And that changes it. I’ve always loved silhouettes because of what they both hide and reveal at the same time. A lot of the details are obscured, and it fuses into one solid image, but it’s got all of these bits of light coming through it as well. So it brings to mind somewhere in between the remains of the animal and the animal itself.

This image from a 1927 glass slide illustrates Chip’s idea that the skeleton is also a silhouette, both hiding and revealing. Unknown (photographer), “Tyrannosaurus rex. left side, January, 1927,” AMNH Research Library | Digital Special Collections

Then going to the bookstore at the Museum of Natural History and buying this large book. It was like three or four inches thick, and this wasn’t some sort of lavishly illustrated book. It was very much a technical textbook on dinosaurs.

Everything was in black and white. But there were all these detailed drawings that were very meticulous based on existing bone fragments. It was a scholarly study of dinosaur bones. It didn’t look like they were using their imagination at all. They were just using what was found.

If you go on Twitter, there are whole memes of people who found the original drawing, and then they compare it to what I did. It’s not hard to find, which is fine with me. I think it’s great, that, like, “Hey, hey, hey, this is where he got it,” and it’s like, “Yeah, that’s exactly where I got it.” Then you can see what I did to it.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice the way Chip set out for the Museum of Natural History? He didn’t have a strict plan. He just went in search of serendipity. And this is the theme you hear over and over in Chip’s story – set everything aside, including your own expectations – so inspiration can find you.

After the break, Chip completes the cover and sends it to Crichton. You won’t want to miss the epic moment that comes next.

The book Chip found in the American Museum of Natural History gift shop is called Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, by Robert L. Carroll. It contains images drawn from the work of Henry Fairfield Osborne, the former head of AMNH. The image here comes from page 214 of Osborne’s 1917 book The Origin and Evolution of Life: On the Theory of Action, Reaction and Interaction of Energy. A free PDF of this 1917 edition is available at Google Books.

Chapter 6: The art and craft of completing

How do you take a creative work to its most perfect, final form? It becomes a logistical hands-on problem.

CHIP KIDD: You did not want this to look like any other book about dinosaurs that had ever been done before. There had to be something about it that was going to be unique.

I’m what I would call a minimalist. So I wanted something that was flat, graphic, in its own way, no frills. It’s going to work when you reduce it to its most essential parts.

I was taking these technical drawings out of this dinosaur book. There was one image of just the skull, that I thought was pretty good, but that sends a completely different message. That means it could be a book about archeology as opposed to, no, the skull’s connected to the neck, which is connected to the body, which is connected to the hands and the tail, and it’s all there. I thought: You need the whole thing, entirely, to get the point across of what the reader’s going to be in for. It’s not about digging these things up.

Then it becomes a very sort of logistical, literally hands-on problem. A lot of the images that I wanted to work with were small. God bless the Xerox machine. If you blew something up 500%, you’re going to lose line quality, right away. Now, if you want to lose line quality, then you’re in luck. But if you want it to literally be sharp, then you have to redraw it.

I just thought, all right, let’s redraw it, then. Anybody who was a graphic designer and illustrator had to learn how to work with these damn Rapidograph pens, the mechanical drawing pens, and, uggh, these pens.

You’d put these ink cartridges in, and depending on how thin they were, they’d clog immediately, so that you had to learn how to hold it correctly, so that if you hold it really totally perpendicular to the drawing surface, then the ink will be able to flow properly. But you got this incredibly fine line. If you make a mistake, you can let it dry and then take an X-Acto knife and scrape away the ink. And then, just experimenting. Just sort of doodling and seeing what the result was, what the effect was.

When you’re looking at the skeleton, you’re seeing these pointy spears of the rib cage coming out, and it looks menacing. The rib cage looks menacing. It’s like, wow, okay, that helps. That helps a lot.

I was doing this drawing and sort of not knowing when to stop, because I don’t want to completely fill it in. It’s leaving just enough to the imagination to imply danger, sharp pointy objects, things that can hurt you.

So at a certain point, I just stopped.

Before digital design tools were common, graphic designers needed a lot of art supplies to get their ideas down on paper – including a stash of Rapidograph pens of various point sizes. The pens needed a special technique and lots of maintenance, but when used wisely, they created a sharp, clear line. Chip Kidd used a Rapidograph pen to hand-draw the T. rex on the cover of Jurassic Park, and an X-Acto knife to make corrections. Photo: Sarah Jeffrey

Chapter 7: The cover we send to Crichton

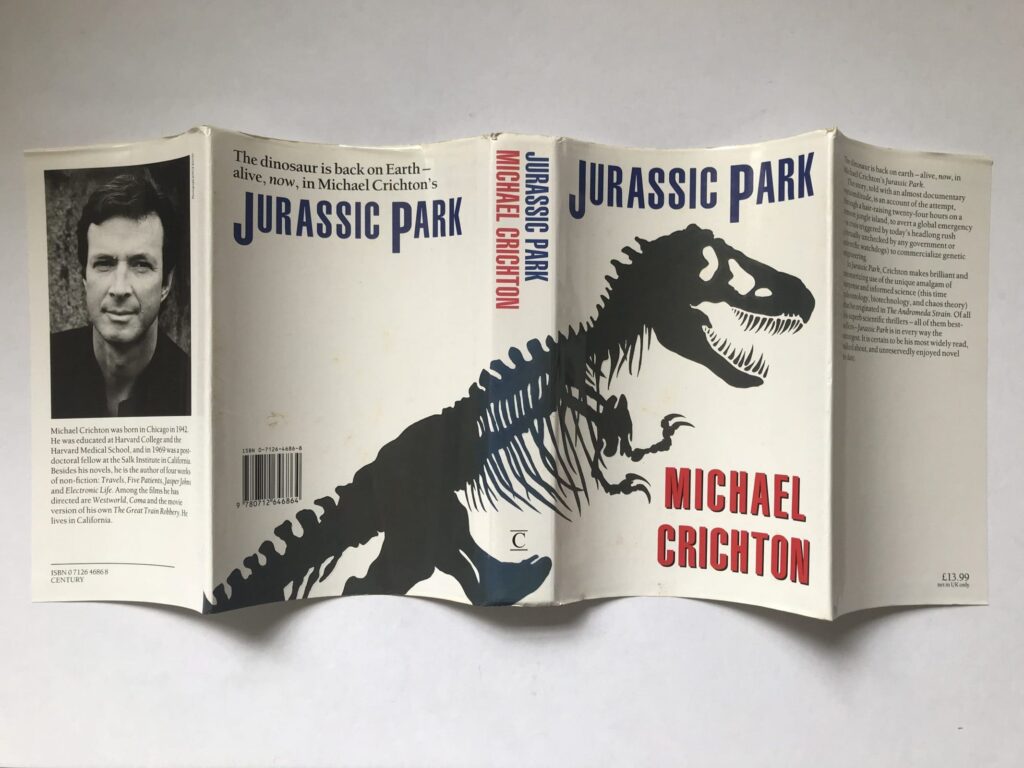

CHIP KIDD: It’s very simple. The background is white, and the skeleton itself wraps around the spine and onto the back. So you get a sense that it’s big, that it can’t be contained on one surface. It has to be free to roam around the entire jacket. Not just the front.

There was some concern that the pelvic bone is purposefully wrapped around onto the spine, onto the back, because just the tip of it was showing on the front, and somebody said, “You know, I really don’t think we should show the dinosaur’s penis on the front of the book.” So I couldn’t argue with that.

The lettering is very what you would call utilitarian, that would imply way-finding signage in a park to say, “This way to the T. rex cage,” or what have you. I felt like, all right, to me, this looks fresh. This looks like this is going to be a book about dinosaurs like no other book about dinosaurs you’ve ever read.

This book jacket from the first UK edition of Jurassic Park shows how the T. rex skeleton body wraps across the back and front of the book, while carefully avoiding placing his pelvis on the front cover. It also shows how the original dinosaur drawing was a very dark green. This edition is listed by John Atkinson Fine & Rare Books (and at time of posting is still available).

Chapter 8: You can do better

How do you learn to take criticism? You set everything aside, and start again.

CHIP KIDD: As a book cover designer, you have obligations to at least I’d say five separate entities. And it’s hard to tick off all those boxes. A lot of times it’s three out of five or two out of five, or worse.

I want to make Crichton happy. I want to make Sonny happy. I want to make the Knopf marketing department happy. I’m actually not really thinking about Steven Spielberg at this point, but I want the fans, the readers to be happy, and I mean, you also have to think about yourself because literally my name is going to go on this.

But the author is always the ultimate say. Morally as a company, Knopf Pantheon, we want the authors to be happy. We’re not going to go to press with something that they hate. Especially in this case.

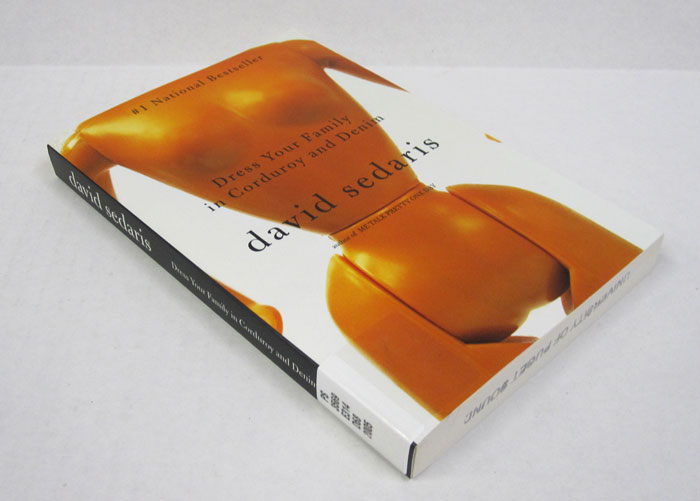

One of the David Sedaris books I was working on, Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim, I just must’ve done eight or nine designs that just were not working.

I did idea after idea after idea, and nothing was getting approved. I didn’t give up, but I just thought, “All right, I’m going to give myself a break from this for a week and work on something else.”

I was doing photo research for a different project. Then, I hit upon this image of this naked Barbie doll in a photographer’s portfolio, and the light bulb went off in my head, idea-gasm. It just clicked. I’m like, “Oh, all right, that’s it. That’s it. This would be perfect for that title.”

And then, at that point I thought, “All right, they’re either going to agree or they’re not.” But they liked it, and it was the best thing. They were right to reject the other things because this was the best thing, and that’s the best-case scenario when either the author or the publisher or whoever says, “You know what? You can do better.” And then, you figure out how to do better.

“Delightfully alienated and neurotic, David Sedaris is one of the greatest living American humorists,” says the Puget Sound Library, who featured this book, with its now-iconic Chip Kidd cover, as part of its 125th anniversary celebration to represent the year 2004.

Chapter 9: The fax machine

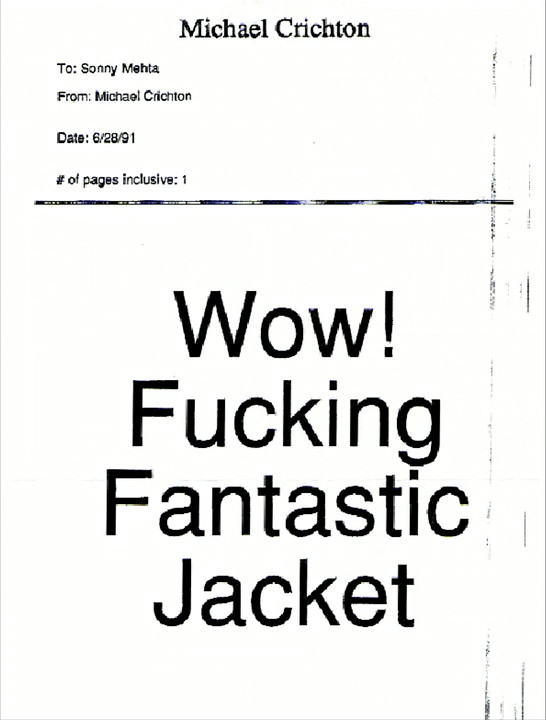

CHIP KIDD: Crichton, he was more of a “sit back and wait to see what you come up with” sort of guy. I show it to Sonny. Sonny either says yay or nay. And at that point, it’s up to Sonny to send it to Crichton. I mean, you sort of hope. You sort of hope, but you never know.

It’s 1989, “Ooh, fax machine. That’s so sophisticated.” And I remember at one point somebody said, “What did we ever do without them fax machines?” Crichton sent back this sort of quasi-obscene expletive about how much he liked it, which was really great. “Wow, fucking fantastic jacket.” I kept it, and I have that.

We had anticipated that the book was going to be a hit, certainly, but we didn’t anticipate how big a hit. I mean, you sort of hope. You can’t control the zeitgeist for something like that.

Michael Crichton liked the cover.

Chapter 10: Coming soon: Jurassic Park, the movie

What happens when your work is adapted? You sit back and watch.

CHIP KIDD: There were all these reports coming in the gossip press. I remember on Page Six in the New York Post about all these problems they were having making the movie. Production would get shut down. And they were trying to do this new 3D computer-generated thing that, it was working, and then it wasn’t working, and blah blah blah blah blah. It seemed like, “Wow, this is doomed.” It’s either doomed, or it’s going to be awful.

My phone rings, and it’s some big lawyer from Universal Pictures and, “Is somebody named Chip Kidd there?” And I said, “Speaking.” And they said, “Well, we want to license the rights to this image just in case we might want to use it in conjunction with the film.” And I know how the sausages are made. I said, “I’m going to have to put you through to our legal department.” And so that was the last I ever spoke to anybody from Universal Pictures.

I used to get this trade magazine, it was more for toy licensing because I was totally into toys. And this full-page ad came out: “Coming soon: Jurassic Park the movie.” And that was the first time that I saw the movie logo. And that was really interesting, really interesting. They didn’t alter the dinosaur drawing in any way. They just added all this stuff to it that my design teacher would not have approved of at all. You know, the stylized typography, there’s little palm trees in the background. The yellow circle. And it just looked so different, and yet the drawing was the same. But that’s showbiz, what are you going to do?

They had a small screening in Manhattan to show us the movie. And this was right before it came out, and then that’s when we saw it. The extent that this was integrated into the film. It’s not just the logo for the movie, it’s the logo for the park. It’s the logo for the park in the movie. People are wearing ID tags with this hanging from their vests in the movie. Everything in the gift shop, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. And I mean, our jaws were just dropping anyway because the movie was so good.

When the book jacket design was licensed for the 1993 movie Jurassic Park, the drawing was unchanged, but some changes were made, which you can see in this photo from Hawaii’s Kualoa Ranch movie tour. The film designers added silhouettes of palm trees, some color, and a circle border to form a round logo; meanwhile, designer Mike Salisbury chose the font Neuland for the words “Jurassic Park.” Photo: Will Fisher / Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

Chapter 11: What this means

CHIP KIDD: It means that I’ll get an obituary in the New York Times, and that will be the first line of the obituary. And hey. When I first came to New York and I was very young, I just wanted to get started doing something creative, and that was the first job that I was offered, but the pay was really low. But I realized that if I kept at it that any design that I did would have my name on it. Book cover designers get credit for their work. And so with Jurassic Park, it says right there: design and illustration by Chip Kidd.

I say it’s definitely one of the most recognizable graphic symbols of the 1990s. You know, I’m enormously proud of it. It’s very strange because once it does get sold to Universal, like, I’m not in the movie credits at all. I’m sure somebody said if we credit him, he’s going to come after us for money. And I guess that’s why they didn’t. So that’s a shame.

So it’s this bizarre thing where there’s a faction of the fan base that knows I did it, but I’m sure there’s a huge, much, much bigger audience that loves the movies and loves the logo or whatever that have no idea that I did it. So it’s just interesting. It’s interesting that way.

In 2014, Chip Kidd’s archives, more than 250 boxes of material and about 1 terabyte of digital material, went to the University Libraries at Penn State University, his alma mater. His student portfolio work, as well as the original drawings for the cover of Jurassic Park, and much, much more, are now housed in The Eberly Family Special Collections Library, complementing their strong graphics holdings including work from Edward Gorey and Lynd Ward. Photo: Wilson Hutton, Public Relations and Marketing, University Libraries

Chapter 12: From cover to cover

How do you turn a single success into a career? Set it aside, and keep doing the work.

KIDD: If you’re M. Night Shyamalan and you get “The Sixth Sense” made, then that makes your career. But in book cover design, it’s not quite like that. We live from cover to cover.

There was no way I was going to be able to do another Jurassic Park. It just doesn’t work that way. You can’t do it. The only thing I could do that looked remotely like it was the sequel, The Lost World, okay? Each book is different. I can’t approach another book cover that way because it’s a different book. It would be, I don’t know, aesthetically dishonest to try and copy it.

There was a series of books that I was able to work on that, I’d say the covers became iconic because the books were iconic, and there was one after another. Okay, you do Jurassic Park, but then you do All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy. And then you do The Secret History by Donna Tartt. And then you do The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. And then you do this cover for an obscure group of short stories called The Elephant Vanishes by somebody named Haruki Murakami. And then you do something called My Name Is Red by Orhan Pamuk. And then you do Naked by somebody named David Sedaris. It’s just the group and the succession and the accretion.

That was more important than any one thing.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Chip for sharing the story of his creative journey. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you got something from it, that you can bring to your own work, whatever your field.

Whether it was the way Chip completely set aside the pressure to create something iconic – and then created something iconic. Or the way he was willing to set aside each idea that didn’t work, to make room for the next inspiration.

Maybe it was the way he did crosswords when he was stuck or discovered the idea for one cover while researching another. Or maybe it was the way he set out in search of serendipity – sketch pad in hand – and coming back with that iconic T. rex.

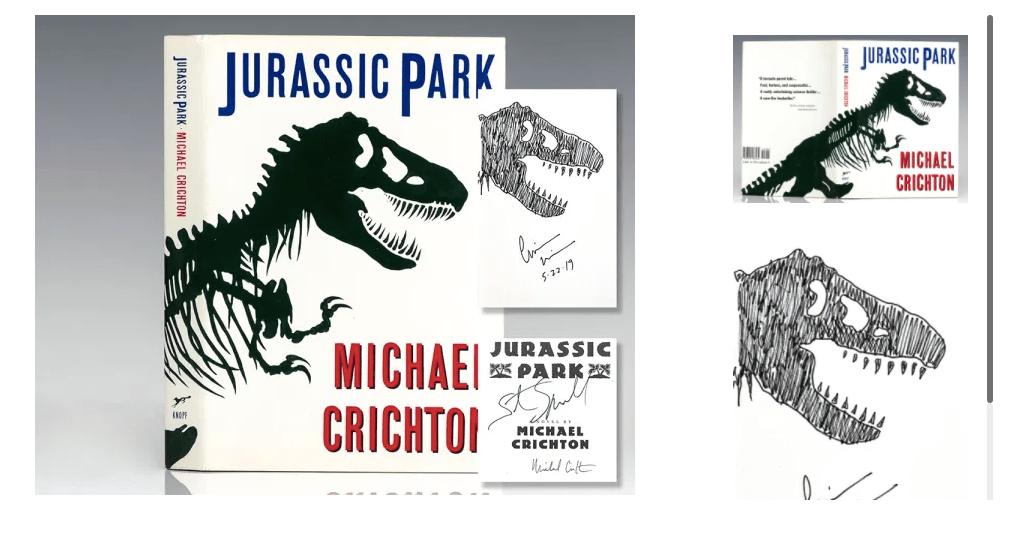

Raptis Rare Books in Palm Beach, Florida, shared this very special first edition of Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park signed by Crichton and film director Steven Spielberg on the title page, and signed with an original drawing by Chip Kidd on the verso of the half-title page. Sadly, it’s sold, but you can browse more in Raptis’ exhibition Jurassic Park at 30.

A tattoo of the Jurassic Park logo that looks like an embroidered patch, from Paul Lukas @UniWatch

About the Creator and Host