Be utterly honest

Capturing an honest moment is one of the riskiest ways to create. But the results are real, and they stand the test of time. As musician Ben Folds tells the story of creating his breakout album “Whatever and Ever Amen” with the Ben Folds Five, you’ll hear a very specific story about a rock band recording an album in a house, instead of a studio, with piano instead of guitar, with lyrics drawn from newspaper clippings. But it’s also a universal story for any creative in any field at any time, about the choices — and pressures — that keep you honest.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: What I was trying to do

- Chapter 2: Ben’s house.

- Chapter 3: Recording a song in one take.

- Chapter 4: We run out of songs.

- Chapter 5: The cassette tape.

- Chapter 6: Writing lyrics vs writing a book

- Chapter 7: An unlikely source of inspiration.

- Chapter 8: Improvisation.

- Chapter 9: Writing the song “Brick.”

- Chapter 10: What I learned when we mixed the album.

- Chapter 11: The battle of the radio.

- Chapter 12: What I thought of the album then.

- Chapter 13: What I think about the album now.

Transcript:

Be utterly honest

Ben Folds wanted to create a great, crunching, emotional, honest rock record on a Steinway piano. With the Ben Folds Five’s second album, he was about to get that chance.

Chapter 1: What I was trying to do

BEN FOLDS: I wanted it to be a real honest record, an event that was captured. The way that an album like that is made is by a real unearned sense of confidence and a youthful sense of cockiness. And where to do it best? A house.

I wanted to sense that we were in that space and that we were capturing an event – as if I was important enough to capture on an event. But that was my feeling.

What the labels wanted to do, and they may have been right, was put us into a studio with a grownup who had made records before, because there are many mistakes to make. It’s a minefield of stuff to do and not to do, time to waste, and getting the best record you can make. The really great reasons for kids like us to go into a studio is important.

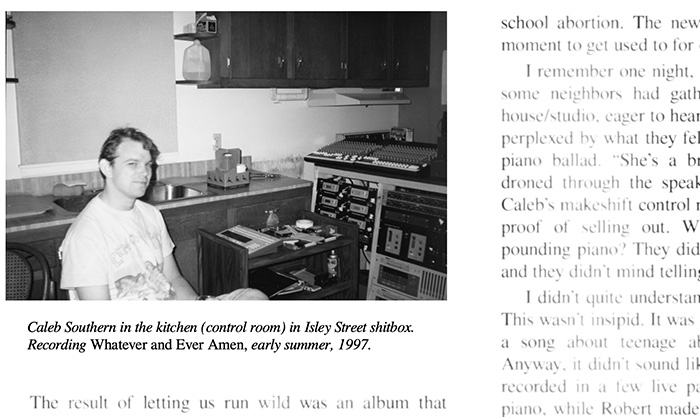

550 Music down at Sony was a relatively new label. I negotiated in just a very cocky way. I was like, “I don’t need any input. I don’t want a studio. I don’t want a real track record producer. We want to use our friend Caleb, who runs sound at the Cat’s Cradle Rock Club down the street. Don’t want to hear from anyone until we’ve mixed it. Would like to have the best mixer in the business, which is Andy Wallace. And no, I don’t have all the songs finished. I’m going to figure out the other half when we start working.”

I think they probably thought that was crazy, but they wanted me to do exactly what I wanted to do. I just thought it should be made in a house.

JUNE COHEN: That’s musician Ben Folds. And he’s about to tell us the story of creating his breakout album, “Whatever and Ever Amen” with his band, Ben Folds Five. It’s a very specific story about a rock band recording an album in a house, instead of a studio, on piano instead of guitar, at the height of the 1990s grunge rock era. But it also has universal lessons for any creative in any field at any time.

As Ben takes us on the journey of recording and releasing this unlikely album, you’ll hear how capturing an utterly honest event is one of the riskiest ways to create. But the reward is something intensely real that stands the test of time.

You’ll hear how Ben and the band decide to record the entire album in a house – and then face challenge after challenge in seeing that vision through. You’ll hear Ben run out of songs, and learn how he finds the creative spark to write more. And you’ll learn his surprising secret for making sure every song felt real and utterly honest – no matter how many times it was rehearsed. And here’s what you should know about Ben and the album.

Ben Folds is a multi-instrument musician, who first rose to fame with his band Ben Folds Five. He’s now a solo artist and an advisor to major orchestras. He wrote a best-selling memoir, and he also hosts his own podcast about creativity, called “Lightning Bugs.”

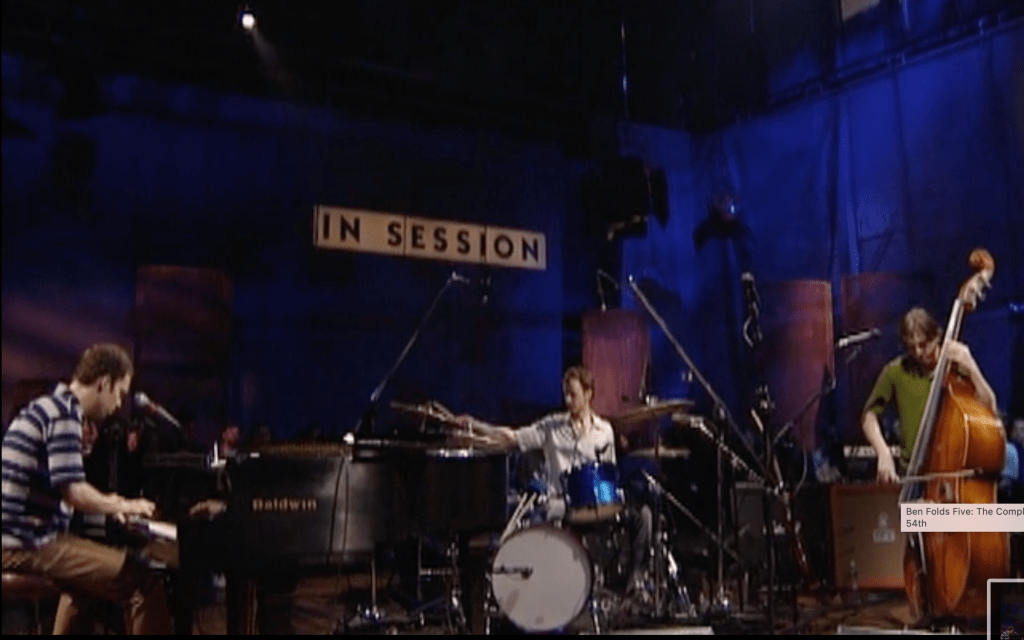

Ben recorded this album with Ben Folds Five. It’s three of them: Ben on vocals and piano, Darren Jessee on the drums, and Robert Sledge on the bass. It was produced by their friend Caleb Southern, and mixed by Andy Wallace. And keep in mind, this was the tail end of the grunge era, and the guitar band was king – but they made this rock album with piano, bass, and drums.

Important note: The piano you’ll hear in this episode is as always our composer Hil Jaeger, who’s playing original music along with the story. For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com/benfolds.

[Theme music]

Chapter 2: Ben’s house

BEN FOLDS: I was confident that you could make a reasonable sounding record in the worst sounding house. Sonically, it was absolutely horrible.

It was a little box of a house in Chapel Hill. I think the whole house has probably 450 square feet. Just a few tiny rooms. It was terrible. It was really ugly. It was depressing. Yeah, it was not pleasant. Half of the problem was that you could hear everything outside inside, and vice versa.

My father is in construction, so we took some of the budget and spent it on him and a crew to come in and soundproof the place. He made it sound way worse than it did.

Every surface was chipboard, medium-density fiber, MDF. It smelled like old rotten cardboard. It was terrible. It was on every surface of the house.

When sound equally bounces off of two opposing reflective surfaces, they meet and go boingggggg, you know that sound? You hear it all the time. You’ll talk or you’ll clap in a place and it goes booinggggg, a great big standing wave where you can’t record anything ‘cause it sounds like shit.

My father, he didn’t know anything about reflections and what makes things sound good. He knew about what blocks sound out. You couldn’t hear anything outside. There was a hurricane that came up the East Coast and settled into North Carolina, and we didn’t even know it was happening because we couldn’t hear it until the lights went off. We crawled trying to find the door, opened the door, and it was like everything was blowing sideways.

I was confident that you could make a reasonable sounding record in the worst sounding house. There’s so many reasons why it can’t be done. I was really sure of myself. I was like, “This can be done.”

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice the words Ben used to describe the house where he recorded the album? It was “terrible.” It was “ugly.” It was “depressing.” You can sense right away the kind of honest event he wanted to capture. And you can also see his approach. He constrained himself to the tools he authentically had at his disposal: His house, his instruments and his Dad. It was risky; his Dad didn’t really know how to build a sound studio. But those terrible sound reflections he created by accident? They actually give the album its authentic, honest vibe that fans would come to love.

One fan called this the “Whatever house” – the small bungalow in Chapel Hill, NC, where the Ben Folds Five recorded “Whatever and Ever Amen.”

Chapter 3: Recording a song in one take

How can you make something that feels utterly authentic? Keep the mistakes.

BEN FOLDS: With the way technology is now you can undo all your bad decisions. We couldn’t do that. We were using these machines where you would have to boil everything down to two tracks and start again. We couldn’t undo anything. A bad decision was a bad decision and was on tape, unless we wanted to record over it.

I had this idea for that song, “Steven’s Last Night in Town” – and I know why this is a terrible idea now – that I should record the vocal of that song across the room. So I was about 8-10 feet from the mic, which was nearly the length of that room, which was my bedroom. And because I was so far from the mic, the mic was cranked up. You could hear all over the house. The guys were listening in the kitchen. The living room was where the Steinway was. The phone was on top of the Steinway. I was trying to get it all in one take. I was almost to the end of the song, and the phone went off.

You hear Caleb, Robert, and Darren – the producer and my band – laughing. They thought that was so funny. It was attached to a cassette answering machine, and so I played it back and found that it was my friend Mike had called. He’s very proud of that. I went ahead and sang through the whole thing and said, “Nah, we’ll just keep the phone.”

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice the tone in Ben’s voice when he said: “A bad decision is a bad decision.” You’ll hear that tone over and over again as he moves through the story of this album and the implications of being utterly honest. It’s riskier than other ways of creating. But Ben utterly trusted in the rewards.

Chapter 4: We run out of songs

BEN FOLDS: We’d gotten half the songs recorded. I was crossing the line between using all my old stuff that I had written for most of my 20s, and I suddenly realized, “Oh shit, I’m out. I guess I’ve got to write some more, and quickly.”

I had that spark. I’m getting this feeling, and I’ve now heard bits and pieces of a melody. I’m walking around, and it’s like, I feel this little chill when one minute passes. I can hear the chords sort of, I know basically where it’s going. And I think that’s my favorite part of it.

Once I get that, I’m happy. And most of the time I would say, I don’t get back to them. I just let them go. I just let a song play out. There’s applause at the end of it. Everyone’s happy. I’m happy. And I never think about that song again.

I don’t like finishing things. I hate finishing stuff. I think it’s the worst – and hate’s a strong word, and I’m going to use it again. I hate it. I hate it because it’s work, and I hate it because it is where I have to divorce myself from all of the joy of the idea.

It’s like, “Oh man, okay, now we got to do A, A, B, A, A, A, B, A.” It’s got to have a form, it’s got to have a time and a key and all these things. And that’s just technical stuff. And I’m not dead sure when I get it finished if I actually translated it at all to the other side.

I remember that I had that spark. I remember that I had the little chill at moments from the song, but I’m never going to get it again from myself.

Chapter 5: The cassette tape

How do you find a new idea fast? Look for the old ones that you threw away.

BEN FOLDS: I lived in Montclair, New Jersey for, I guess, almost a year. There was a month where I was pretty depressed. I was living in an attic, and I was just completely by myself.

I brought a Wurlitzer electric piano, one of the really old style beige ones, which is all I owned. I didn’t have a car or anything like that. And I don’t know how the hell I got it there to tell you the truth. I usually have a song melody in my head when I wake up, and I thought I should wake up and the first song that pops into my head, I should put it on a cassette.

We were coming up to the end of the recording time, and I found that cassette tape. “Battle Of Who Could Care Less.” And I thought maybe that was a Stevie Wonder song, “Just Enough For The City.” Something about that.

“Selfless, Cold, and Composed,” there was one string line in that, that kept coming back to me. I just completely heard, and it’s like (singing). And I would have told you that those melodies were pretty shitty, stuff that I thought was terrible that I threw away. That was the stuff that finished the album.

Chapter 6: Writing lyrics vs writing a book

How can you compact a big idea in a limited space? Be poetic, be succinct, but tell the story honestly.

BEN FOLDS: How many words does a song have in it once they’re repeated? Do you have 45, 50 words in a song? And a lot of songs tell an entire life story inside the song.

Songs are very bossy with time. They insist that every time you get to a minute and 15 seconds this word is coming out. It’s very precise. It’s intimidating to try to paint something large inside a song, because it’s only three minutes. And a lot of that’s going to be repeated. There’s only a little bit of syllable real estate, and it’ll also be confined by the emphasis on each syllable. It has to fall a certain way. And that can be intimidating when you’re telling a story, like, “Where’s my space?”

With a book, the reason it’s intimidating is because it’s just so much space to fill.

My kids are twins. I realized that what happens in childbirth with twins is that, when my son was born first, the second one has not been used to that much space and just flips out, kicks everywhere, turns upside down, comes out posterior, is going to have a hard time, like, “Oh, woah, I’ve got so much space.”

You don’t have the space that you think you have. You begin to realize that, even if you have 300 pages to do it in, only the poetic is going to suffice. The details have to be right. You have to be succinct, and there’s got to be a better word than real, but that.

Chapter 7: An unlikely source of inspiration

How do you create something authentic? Look for true stories, wherever you find them. And then, mix and match.

BEN FOLDS: In the south, the county people are very country, and they have different accents. If you go into Atlanta, yeah, you’ll hear Southern accents, but they’re a much more cosmopolitan accent. You get just outside of Atlanta then you’re in the county. And I lived back and forth between the city and the county as I was growing up. And I was working at a grocery store, which was absolutely county as it got.

Mom and pop store that took care of their employees – these ladies that were the cashiers, they had all been there for years and years, and they just all read the obituaries. And it was fucking depressing. I mean, I was sitting in the break room for my lunch, and they were always reading the obituaries out loud. Some people write poems and all kinds of special things for people who have died.

And I started really digging to try to sum up someone’s life in the newspaper. It gets thrown away the next day. It’s just, I don’t know, something about it. It’s like, “Wow, that’s their life.” And look, their family are like, “He’s in the paper. Jeffrey finally got in the paper for dying.” There was something really interesting about that to me. So, I would often cut them out, put them in a notebook and just make a little song to it. I didn’t know if anyone would ever hear those. There was one in particular that I really liked. I think I kind of robbed that melody a little bit for the song “Cigarette,” which is a song that I took a run-on sentence from another newspaper later and kind of shifted it around and made a melody out of it. You can see it’s a mess. You’ll have ideas and they might fit here, they might fit somewhere else, and sometimes it takes a while to find a home.

Sitting in the back room of the grocery store where he worked in Winston-Salem, Ben Folds grew fascinated with the lives described in the local obituaries. One of these miniature life stories helped to inspire the song “Cigarette.” As fellow Spark & Fire guest Rubén Blades says, “If you all of a sudden run out of ideas, buy a paper.”

Chapter 8: Improvisation

How do you create something that feels authentic, even when it’s rehearsed? Discover the idea along with the audience.

BEN FOLDS: That album enjoys my need for a deadline. A deadline makes you let go of it, you have to at some point. I learned a trick of discovering a song as we were recording it. There’s something really cool about going, “Wow, this chorus is pretty good. Is it finished? I don’t know, record it. One, two, three, play.” And it’s there, and it’s done.

It’s about everyone discovering something at the same time. The performer is not any more in the future than the audience is. When you prepare something, if you’re an actor, you’re trying to act surprised, “Oh my God, he’s dying,” but everyone knows you learned the lines. So, you’re trying to fool them. A good rock concert, there are lights, there’s production, there’s mics and stuff. We can have everything planned and the set list down to within an inch of its life. The audio engineer knows just where to turn the echo in. It seems to separate you from the audience.

But when you start to improvise, you’re suddenly just all in the same space. When you’re improvising, you’re getting the memo at the same time as everyone else, you’re getting the feed, and you’re spitting it out there. And I’m as surprised as anyone at what is coming out.

If you can just go, “That’s a moment. Everyone’s a person here. I’ve got some ideas. I got the mic.” If you can break down the formality for a second at any point in a performance, it’s powerful. If an audience is discovering something as the performer is discovering it, there’s nothing better in recorded or performed music is that mutual sense of discovery.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how Ben just turned his idea on its head? Instead of just capturing utterly honest moments, he found a way to create them. In the midst of rehearsing and recording and re-recording, he uses improv to make the moment real again, for himself, and for his audience. And that’s a technique you can use in any field.

After the break: The terrifying moment when Ben hears the album for the first time.

Chapter 9: Writing the song “Brick.”

How can you solve a creative puzzle? Fit together two pieces that don’t belong together.

BEN FOLDS: I guess in the back of my mind, it was a subject I had wanted to write about at some point. And this is where a deadline comes in handy because it forced me to move quickly through something that almost in any era might be one of the least advisable things to write about, which is teenage abortion, especially if it’s a true story,

I got to finish this record, and it needs to be real, and this is something I’ve wanted to do. It’s around midnight. I was just sitting at the piano thinking, “What is the music for that?” I chose a major key because I didn’t want to over-sadden it. I wanted it to be sad, but I wanted it to have a sense of numbness to it. And my right hand came out, and I had an acoustic guitar there, and I was also going back and forth between the acoustic guitar and the piano. And it’s very playable on the guitar for that reason. It goes back and forth between both those.

I was like, “I have verses. I can see that I have a story. I don’t know how to sum this story up.” And then that’s when I remembered that Darren, the drummer who’s a really great songwriter, had showed me a chorus, which seemed to mean nothing, which was: “She’s a brick, and I’m drowning slowly.”

And I never knew what he meant by that. I still don’t know what that means. One thing I knew about that chorus was that it had a vibe. It was just like an instant vibe. And I just tacked them together. The sun came up. At some point, I went and got breakfast, called Darren, showed him the song, and he really loved it. He liked the way that the two things fell together.

As they worked on different overdubs on the album for the next couple of days, I went off by myself with a notebook, and I just really tried to pound out the details in a way that told the story, rhymed, weren’t judgmental. There were a couple of times when Darren said, “I think you were more on it when you used that passive tense.” It’s like, “Really?” He’s like, “Yeah, I think that was feeling it more.” “So thank you. Thank you. I’ll go with that.” I think I had a more dramatic sense of a bridge and he was like, “That’s not you. It’s too dramatic.” And I was like, “Yeah, yeah, you’re right.” So I toned it down a little bit.

We recorded pretty much everything in a single bedroom. There’s where the drums were. The piano had just been moved in. Robert had never played upright bass before. We thought we’d try that out. Anything but brushes got into everything else’s mic. We kind of balanced it out like that in the room. We recorded it in I think the second take. The actual process of that was fast and furious. I tried really hard to keep it utterly neutral – utterly neutral of judgment, utterly neutral of almost everything except the feeling of what it was.

JUNE COHEN: There are so many creative takeaways in this story of writing “Brick.” Like, did you notice the way Ben turns to his band to keep him honest? Darren points him to the version of the bridge and chorus that was most authentic to Ben. And that’s a technique to remember. In the course of creating anything, it’s easy to lose sight of what’s utterly honest to you. And that’s when you need a collaborator to steer you back to your own authentic self.

In this 1997 performance of “Brick” from the PBS series Sessions at West 54th, you can see Robert Sledge on a bowed double bass, creating a quiet, intimate sound. Click through to see a clip of the whole song.

Chapter 10: What I learned when we mixed the album

BEN FOLDS: Well, I learned that it’s not finished until they pry it from my cold, dead fingers.

I was not sold on the sound of the record. Surprise, it wasn’t recorded in the studio. Oh, it was really scary. This is it, we’re fucked because this record doesn’t sound right.

There were things about it I just thought should be happening like, “Why aren’t the drums punching? Why did that feel like that?” It drove me crazy at the beginning of “One Angry Dwarf,” and the drums come in like… They do this thing. And I’m like, “Why isn’t that hitting us in the face?”

Your average single in that era probably would have up to 36 to 48 channels of sound to mix. For the song “Brick,” there were six faders to push up, six channels, a couple on the drums, a couple on the piano, bass, a little vocal. Bob’s your uncle, as they say here in Australia, you’re done. And it was incredibly, I mean, it was audacious as shit. When Andy was pushing the faders up, he was kind of joking. He was like, “Well, we can do it this way or we can do it this way.” And he pushes one or two little faders and they don’t do anything. There’s nothing to do. It sounds like what it sounds like.

We were doing a European tour, and I was just flipping out. If I’m in Europe and I want to keep scrapping, I can keep doing it. We can keep doing it. I would call the mixing engineer, Andy, from a payphone somewhere in France or England or something.

I would have them do recalls spending all kinds of money. All the money I thought we were saving by doing it in the house instead of the studio was probably spent doing recalls. It’s not like now where you just pull up GarageBand or Logic or Pro Tools, and you just get your mix again. If you want to relive the mix, you have to rent studio time and a bunch of assistants, and they get pictures out of where all the faders were, and they put it back, they try to balance against a big deal. His assistant would say, “Look, we did the best we could with what you gave us. There was nothing there. You’re asking us to put something in the mix that doesn’t exist.”

The things I had them recall were sounding increasingly worse. Eventually, thank God the clock ran out, because I was ruining the record in the process.

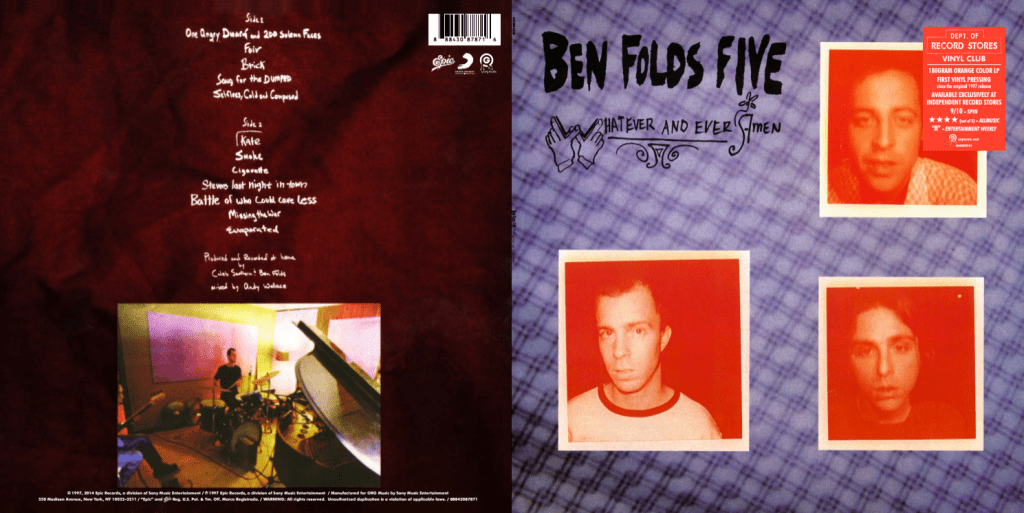

Eventually, yes, Whatever and Ever Amen was released. After a slow start (see next chapter) it’s become recognized as a classic record. In 2014, Department of Record Stores released this remastered version of Whatever and Ever Amen on vinyl.

Chapter 11: The battle of the radio

How do you compete with the loudest voices? Tell a deeply honest story – quietly.

BEN FOLDS: We were going in a really competitive atmosphere. In that period, the grunge era, what was competitive was loud. You get loud. That’s how you compete. All these loud guitars, all this loud emotion, make it loud.

There are a lot of good reasons why there aren’t piano, bass, and drums acts out there. There aren’t any. There aren’t any. There have never been any. The guitar fits into rock and roll in a way that defined rock and roll, and it is huge and it has all kinds of energy.

Our first single, was “One Angry Dwarf.” The second single was “Battle of Who Could Care Less.” Surprise, we weren’t rocking like the guitar bands were rocking. Why? Because we’re a piano band. That doesn’t work that way.

Those singles sounded bad on the radio, quite honestly. They did. I would hear them sometimes and just sink. It wasn’t until “Brick” that we broke through.

I remember it really well. It was cold. I was with my friend Mike Oldenburg, who was the friend of mine who called on the phone, who immortalized his jackass self on my album. A band called Bush played right before in all its $500,000 recording budget glory. It was loud. He sounded great. The band sounded great. It was massive. They said, “Next up, a new single from Ben Folds Five.” And I was like, “Oh my God, this is going to sound so bad. Here we go. Now comes these little dudes. How many times do I have to hear myself sound shitty on the radio before I get humble?”

It sounded massive. It sounded twice as big. As it turns out, when you record quietly with a piano, and you turn it all up, you enjoy the psycho-acoustic sense that you’re whispering, and it’s as loud as the other guy’s shout. And it’s so powerful because you could yell. Everything is balanced so that I can hear the drummer, the drummer can hear me, the bass player can hear everything, we do it together like that, it’s huge.

Chapter 12: What I thought of the album then

BEN FOLDS: It was a disappointment. The album wasn’t as good as I thought it should have been. It didn’t sound as good as I had wanted it to. I was really aware of the times where I choked the life out of it. It wasn’t nearly as successful as it should have been. All the metrics of the music business constantly put you just a few inches behind the carrot. It just keeps dragging along.

It’s like, “Wow, you guys have had the first radio success with a ballad on modern rock.” Really, we have? “Yeah, except this week, there’s one that looks like it’s going to probably overtake you.” Oh really? What’s that? “It’s this band, they’ve got a song called ‘Bittersweet Symphony.’ It seems to be doing pretty well. It’s in a Nike commercial.” Really? Is it beating us? Next week, no one had heard of us anymore. Everyone had heard of that. I was immediately cast into this vapid competition. It’s like, well, this album has now barely become platinum. It really should be double platinum pretty soon. But no, it wasn’t. The label will always put more money in when they see more money coming in. So we always lost money. So it seemed like the album had failed.

And when we made the next record, some might think that the reason that we didn’t go for “Brick” part two is because there was success in it, and it’s fear of success. I just saw the failure in the whole thing. So I thought, why would you want to do the same thing again?

So emotionally I found it a complete rollercoaster. Yeah, I was rocking and rolling. There were a few years I had a hard time. No one wants to hear the woes of someone who’s gotten what they asked for and what they want when everyone else would like, which is some success in something. But your mind is not set up for it. If you’re a thoughtful person, I think, it especially makes it tough. So I was definitely a “glass has not got any water in it at all guy.”

Chapter 13: What I think about the album now

BEN FOLDS: When I look back on it now, I’m like, “Yes, it’s a good record. It sounds good.”

It was a product of a cocky asshole, but it was the right stuff to do. I thought I knew everything. I was not aware – almost ever – properly of risks. I still hear all the same stuff that I heard on my tour bus in Europe and all the stuff I heard when it was not competing well on the radio, but I think I got it right.

I think the record that we made was a product of the time, and I’m thrilled that I stuck by my guns in my cockiness when I insisted on an honest event, that it would be an honest event. And that means if there’s a part where there’s a phone that went off, we left it. We left stuff between the songs, talking.

When I listen to music now, I hear my contemporaries, and a lot of them is producers who are extremely talented, making records in an environment where you can’t make a record like we made. There’s a quality of what we did that was so 20th century and so allowed by the circumstances. It’s the real thing. I’m hearing the real deal. I’m hearing three guys and their chemistry, songs that were written about something, captured honestly, warts and all. I’m hearing the walls of the house, and you couldn’t recreate that. So I am proud of that.

We really live in an era of puritanical bullshit where something is right or something is wrong. And morally, that might be true, but music and art is about painting the grays in between all that stuff. You are right by virtue of the fact that you felt it. People aren’t very good at thinking. We’re not very good at predicting the future. We’re not really very good at even running or killing other things or not being killed. We’re not good at a lot of stuff. What we are good at is feeling and imagining. We’re so good at those things.

If you feel, that’s valid. You can’t change that. If you can explain it, if you can actually explain it, you’ve made a piece of art, and there’s no other species that can do that. And it’s right, because you did it. It’s so intimidating. All these people have made these things. Yeah, learn the rules, learn the scales, learn your colors and your paints and vocabulary and read your history and all that stuff. You must do that. But in the moment that you are explaining your feeling, you’re the only one to do that. There’s only one right answer. It’s better than saying, “Don’t worry about what people think,” because of course, you’re going to worry about what other people think. Worry about what other people think, be competitive, compare yourself to others, all that shit. That’s fine. But do it honestly. Just do it. You are right all the time if you’re explaining your feelings.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Ben for sharing the story of this creative journey with us. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you found things in it that you can bring into your own creative practice.

Whether it’s Ben’s audacious decision to record something utterly honest – on his own terms, in his own house. Or the way he draws from everything – obituaries, sentence fragments, old tapes – to tell an honest story.

It might be the way he uses improvisation as a tool to make an honest moment out of something that could have felt rehearsed. Or it might just be the way he sees “Whatever and Ever Amen.” How he originally saw the album as a failure, but looks back at it now as the “real deal” – the kind of success that embraces the risks and the rewards of creating something utterly honest.