5 ways to handle creative conflict

Creative conflict can destroy a work-in-progress — or it can push your work beyond good to great. What matters is how you respond. We’re going to hear from 5 creators in 5 very different fields who share actionable strategies (and great stories) about how to recognize, resolve, and harness conflict to create work that is visionary.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

5 ways to handle creative conflict

KRISTEN ANDERSON: So we would get in fights.

ROBERT LOPEZ: We’d get in lots of fights.

BILL T. JONES: Now, here we have a little dissonance, don’t we?

BILL HORBERG: You have to have tension. You have to have conflict for it to get strong.

CRISTELA ALONZO: The network’s furious. The studio’s furious. The writers are furious. How dare I?

RUBÉN BLADES: But I wanted them to understand that my point was to create that tension and break it.

CHRIS MCLEOD: Those are the iconic creatives on today’s episode, talking about moments of conflict on a creative journey. You’re going to hear from 5 creative teams in 5 different fields offering 5 different strategies for how to move through creative conflict.

When there is conflict on a creative team, the first thing to know is that it’s normal. It’s how we move through it that matters. Knowing what to do when conflict arises is a key moment on any creative journey. If we handle conflict strategically, it has the ability to make a creative team even stronger, and a work even greater.

Today on Spark & Fire, we’ll hear from creators who have learned how to move through conflict on a creative team.

I’m Chris McLeod, the Executive Producer of Spark and Fire. I spend most of my time editing our guests’ stories — and shaping them into the episodes you hear. Along the way, I absorb a lot of wisdom that I get to carry into my own creative practice.

Here are 5 strategies for moving through creative conflict.

Our first strategy gets straight to the heart of how to deal with any conflict, creative or otherwise — letting go of your ego. It comes from Kristen Anderson Lopez and Robert Lopez, songwriters of the Disney film Frozen.

When any two creatives come together who care deeply about making something great, it can get complicated. When they happen to be married, it gets even messier.

Strategy 1: Let go of your ego, and play

Spoiler: “Frozen” goes on to become a huge hit, and the cast album tops the Billboard 200 chart some 13 times, breaking the record for an animated film soundtrack. But what seems inevitable in hindsight was anything but in the moment. Singer Idina Menzel (center) and Frozen songwriters Bobby Lopez (left) and Kristen Anderson-Lopez pose with gold records. Photo: Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images for Disney

KRISTEN ANDERSON: Early on in our collaboration, every time we had to write a big song, we could sometimes get really competitive over credit and also control. It felt like a race for who’s going to come up with the best idea because whoever comes up with the best idea gets to control the song. And that wasn’t serving us really well. What happened is we always got in a fight.

ROBERT LOPEZ: She would start writing before I was really ready. She would come to me with some stuff written down and it would upset me.

KRISTEN ANDERSON: I generate ideas from scribbling. I have to start the actual physical act of writing something to prime the pump and just get a bunch of stuff out there. And I think Bobby used to be really threatened by that.

ROBERT LOPEZ: I would be like, “Hey, I’m part of this too.” And then I would try to control the flow of creativity and try to put her down a little bit, which was… That’s not the way to do it.

KRISTEN ANDERSON: So we would get in fights.

ROBERT LOPEZ: We’d get in lots of fights.

KRISTEN ANDERSON: He was like, “We do everything in the room together.” And I was like, “I can’t do it together in the room with you. Because you’re mean when you write.”

ROBERT LOPEZ: And I would be like, “I’m mean because that’s what makes us good.”

KRISTEN ANDERSON: And then I would be like, “I don’t know if I should be married to you. Maybe we should just have sandwiches.” We’ve learned over the years that we do have these very different strengths. We really compliment each other in so many ways. Like we’ll talk and we’ll talk and we’ll talk and we’ll talk, and then I’ll be like, “I need to go brain drain now.” Sometimes we both brain drain. Sometimes he just goes to the piano while I’m brain draining. Then we have a lot more of a grab bag of things to really find, what’s this going to be to congeal some form.

KRISTEN ANDERSON: You really have to be able to play and feel safe playing. I know we just acted out the worst version of that. That’s a play date gone bad. But in general, why I love what I do every day is that we get to take these stories and these characters and then just play in a room. Literally sometimes acting them out … Bobby channeling the essence into some music. And we’re just improving together and that’s play and that’s really fun. And you’re not worried about time. You’re not worried about who’s doing what, you’re losing yourself in the flow of fun.

CHRIS MCLEOD: It’s so refreshing to hear Kristen and Robert laugh about their fights, not only as creative collaborators, but as partners.

I love the idea of handling creative conflict by simply returning to why you love the work you do, and just having fun with it.

Our next strategy is about when your creative team ignores your vision. When you are pushed aside, and have to watch your own project chug along without you and turn into something you don’t even recognize.

It comes from actor and comedian, Cristela Alonzo. When she was creating and starring in the sitcom Cristela, she had to learn the hard way how essential it is for someone to listen.

Strategy 2: Make yourself heard

The cast of “Cristela,” ABC’s sitcom based on the life of creator Cristela Alonzo. Photo: Adam Taylor/ABC

CRISTELA ALONZO: I was in New York doing The View because it was hiatus week, and I ask to have the script because the next day we’re going to do the table read. The showrunner refused to send it to me, and I couldn’t understand why. And then I’m getting on a plane back to LA. They finally send me the script, and I read it and I hate it.

In the show, there’s this character who seems narcissistic, but she’s smart. I said from the beginning: She’s not dumb. She’s smart in different ways. I kept saying, “That relationship is Wicked. It’s Elphaba and Glinda. They are complete opposites, but they find a way to get along, and they both learn from each other.” The script I get is that she suddenly has a photographic memory and that explains, now she’s suddenly smart. No reason, no rhyme, no anything. It’s just now, it’s Brady Bunch and we’ve invited Cousin Oliver to come in. You know what I mean? Now I have no idea what we’re doing. To me, it just felt like very lazy writing.

I realize my plane has no wifi. So it’s New York to LA, no wifi. And I just send this email really quick while we’re in the plane and I’m like, “This is insane. No.” And I get an email back saying, “Why don’t you just read it like that for tomorrow and we’ll fix it later?” Which — that had been used for a couple weeks now and nobody was listening to me. No, I got tired of it.

So the next day, I throw the table read, which you don’t do. I read it poorly. You can see I don’t like the script. After the table read, everyone is furious.

The network’s furious. The studio’s furious. The writers are furious. How dare I? How dare I do this? And I told them, “You didn’t send me the script. You haven’t been listening to me. No one has been listening to me, but you’re listening to me now.”

That week, I was the villain. And I tell that story because I want people to know that it’s not okay to do that.

We ended up getting a new showrunner in the back nine, the last nine episodes of the season. This man respected me as a person and listened to me, and I didn’t realize, until he did that, how much I needed that. I would do anything for this man.

CHRIS MCLEOD: Every time I hear this story, I’m struck by Cristela’s advice: She said, “I want people to know it’s not okay to do that.” She’s not suggesting for people to become the villain when conflict arises. But it reached a point where she knew it was time to find a collaborator who listened and respected her.

Our third strategy about how to move through creative conflict shows how important it is to get this right, especially when the state of the world is in flux. On our episode with choreographer, Bill T. Jones, he and his Associate Director Janet Wong share the story of creating the modern dance masterpiece, Afterwardness, in the middle of the pandemic.

We all remember 2020. It was a reckoning of racial injustice in the wake of the murders of George Floyd and Brianna Taylor. Bill’s whole team wanted to make a difference; the conflict was about the best way to do it.

Strategy 3: Give your collaborators agency

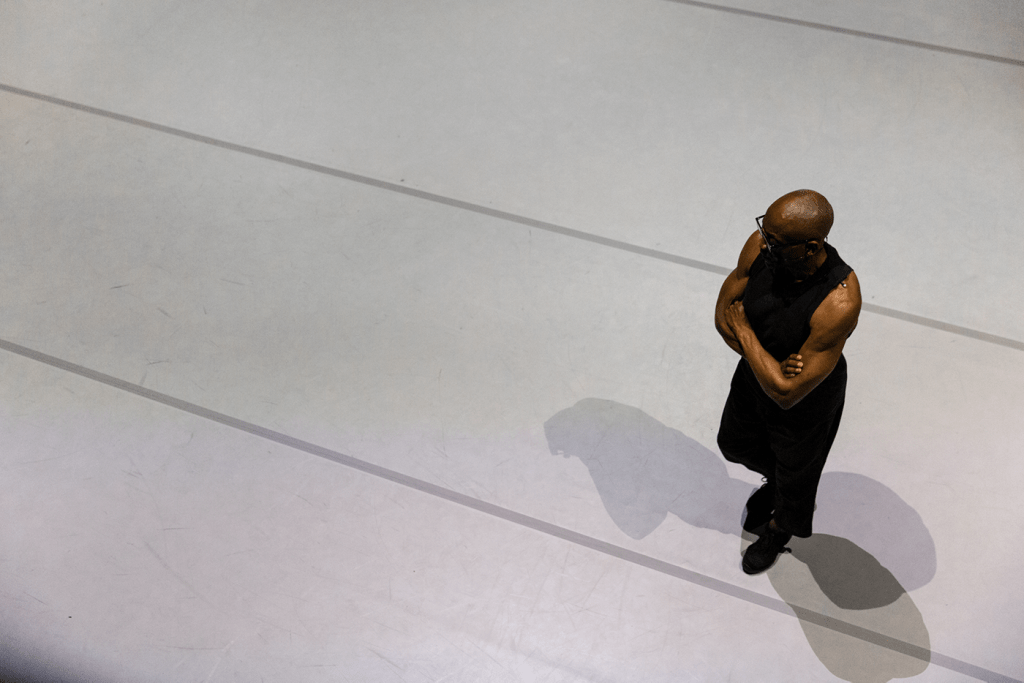

Bill T. Jones, in rehearsal for Deep Blue Sea. Photographed by Maria Baranova.

BILL T. JONES: I believe it’s Yeats who said it. “Art making happens when something is being pushed against.” Artists have an embattled relationship to the world — a world that is constantly telling them what they should and should not do. Art is often a form of rebellion. Many great works of art happen because of those forces of psychology that threaten to cut off our voice, and art is a muscular assertion that I am here, and I do speak.

Chanel Howard called and said, “With everything going on in the world, I can’t be on this call.” The night before, George Floyd had died on camera. And she was, as a young Black woman, woke Black woman, you want me to come on a call and do modern dance coaching? Now, here we have a little dissonance, don’t we? “This is your job, honey.”

“I know, but this is a bigger time than even this job.”

I was really pissed. We had words. “The dance world, the art world, are all products of this white supremacists’ patriarchal system, and we should not be part of it.”

Wait a minute, hold on. “Aren’t you expecting your check at the end of this week? Does it matter that these rich white people on my board are paying?”

“We’re thinking about the future. We’re thinking about what we should be doing, and you, Bill T. Jones, you should use your privileged position to be doing this. If you’re not part of the solution, then you’re part of the problem.”

This was not said overtly, but that was coming out of things, comments that were being said. And if you want to insult an old rebel, tell them they’re no longer a rebel.

Oh boy. “Are you saying that I am the oppressor now?”

“You raise your voice at people. You have power over people. Yeah, you are part of the problem.” Oh my God, have we come to this?

I wanted to run away.

JANET WONG: Around June, Michael Lonergan, producer of the Armory, he would like to offer us a commission for a socially-distanced work.

BILL T. JONES: They said, “We’d like you to make a piece.”

JANET WONG: The room was charged with people who really had something to say at this moment.

The dancers have a lot of freedom. A lot of it is set and choreographed, but they have a lot of choice and decisions to make. I think that also allowed them to own the work. They are part of making of this piece. And it’s made there and then.

BILL T. JONES: You give them agency. They make choices. They can choose to jump in and jump out. Agency … that word is very important in making work like we make. How can people be given agency? Or how tolerant am I to people taking agency?

CHRIS MCLEOD: My favorite line in this clip is the Yeats quote: “Art making happens when something is being pushed against.” For Bill, the “pushing against” comes from his younger dancers calling him out for his position of power.

And this conflict is uncomfortable and hard to hear. But Bill leans into the dissonance. He gives his dancers the space and freedom to express what they want to express. He gives them agency.

Our fourth strategy comes from salsa legend Rubén Blades. When he was writing the genre-defying song Pedro Navaja, he broke the cardinal rule of salsa — and his band wasn’t pleased.

Strategy 4: Put the work first

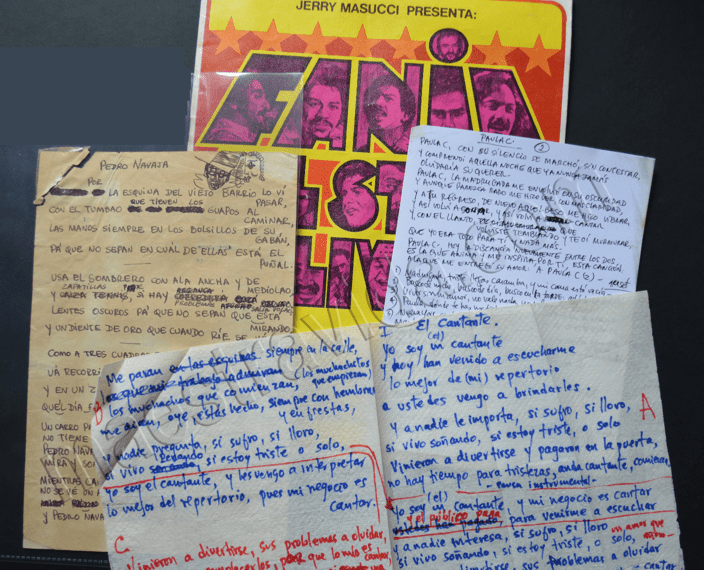

At the Ruben Blades Archives at Harvard, among the many feet of archival material, is a collection of handwritten song lyrics – including the first “Pedro Navaja.”

RUBÉN BLADES: I don’t write music to the point of writing an arrangement, I never had that advanced studies of music. So, I called upon a friend, a trumpet player, wonderful musician and wonderful person, Luis “Perico” Ortiz, to write the arrangement for “Pedro Navaja.” I explained the song to him. I said, “Don’t think of this as a straight-up salsa song. Furthermore, I want you to interrupt the flow for the dancers.” Dancing requires to follow the clave, which is this — this is clave. And dancers use that as a sort of guide. If the clave is not going with the rhythm, dancers are lost.

So, when the mambo comes, I ask Luis, “Break the clave. Break it. I want the dancers to all of a sudden stop and feel like, what the hell happened?” It changed, because lives are changing in the song. The mambo is the instrumental part; it’s the moment where any salsa song shows what it is about. I want that moment broken. I want people to go, “What the hell happened?” Because that’s the question I want people also to make of the song: “What the hell happened here?”

You have two people in the street, and then you have a drunk that thanks God, as if God was his accomplice, after two people were killed for this, and then he moves on. Life moves on. It’s like, hey, get over it. Get back to the clave and keep on moving because that’s it, you have to move. Life is full of surprises, okay, now move. Keep on moving. And Luis “Perico” Ortiz did a wonderful, wonderful arrangement, and he got a lot of criticism for it.

When we were playing that song with Willie Colón’s band, at the beginning, the rhythm section, which was, uh, Milton Cardona, God bless him, and in the bongo, Jose Manuel Junior, they weren’t very happy about the breaking of the clave, ’cause they’re like, real standard defenders of the clave musicians.

And I could understand their point, but I wanted them to understand that my point as a writer was to create that tension and break it, break the tempo in that moment, have people stop and have to come back to it again. So, as life is, in that moment, you stop, and then you pick up the clave again, and then you go back to your groove. It’s not the end of the world, is what I’m saying. Life continues.

CHRIS MCLEOD: Rubén knew that what he was doing would cause conflict. But this wasn’t about his own ego, it was about making a great song. If Rubén had avoided the conflict, like I often do, then Salsa would have never been the same. Rubén put the work first.

Our final strategy about how to move through conflict shows why it’s not something to avoid, but something to embrace. It comes from Queen’s Gambit producers, Bill Horberg and Allan Scott. When you’re working on a project for over 30 years, tensions can get a bit high.

Strategy 5: Embrace the fire

The long road to this shoot for The Queen’s Gambit in 2020 (featuring Thomas Brodie-Sangster as Benny and Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon) begins in another century. Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix © 2020

BILL HORBERG: You have to have tension. You have to have some honest conflict through something for it to get strong. These movies get made well out of the fires. You know, if it’s a happy set with happy people, and there’s never any conflict or disagreement about anything, you can be assured you’re going to fall asleep by the 15th minute of the film.

ALLAN SCOTT: If somebody says to you, “That seems boring,” and you say, “Hey really, I find it quite interesting.” “No, no, no. It’s deadly boring.” Just somebody’s conviction that it’s boring makes you look at the damn scene again. And if you’re lucky, you manage to take out the boring bits. It’s really about listening and trying to make the thing better.

BILL HORBERG: I mean, Scott and I have been friends for 35 years, but, man, we had some epic battles in the post-production and editing of Queen’s Gambit. We were intending to make a six-episode show. The assembly of everything we shot was about 10 hours long. It got to a point where I said, “I don’t really see how this is ever going to fit into six episodes without throwing out a big plank of the story.”

It just got hard for Scott because he had spent a year of his life writing this thing with Allan and then another eight months shooting it. And he had a very clear idea of how it was meant to lay out and then to let go of that and let the material recommend its own best structure.

It was a little bit like chess. It’s like moving all these pieces around the board to find this structure that we ultimately arrived at.

I was just really pleased that it was so well handled and so well dealt with. It was one of the happiest units I’d ever visited.

CHRIS MCLEOD: I love how Bill says that a conflict-free set will most certainly create a boring TV show.

Even if conflict hurts, they understand that it makes the work better. If there’s something to fight about, it means that you’re passionate about what you’re making. They used that fire as fuel to make something great.

We hope you enjoyed this episode of Spark & Fire. Maybe what you’ll take with you is Kristen Anderson Lopez and Robert Lopez’s strategy: sometimes you need to let go of your ego and play. Maybe you’ll take Cristela Alonzo’s advice of finding a collaborator who listens. Or maybe it’s how Bill T. Jones responded to conflict by giving his team agency. Or Rubén Blades’ technique of putting the work first. Or maybe the strategy you take with you is from Bill Horberg and Allan Scott — that to make something great you need to use that fire as fuel.

Whatever you took from this episode, we hope that it brought you insight that you can bring into your own creative practice. To move through creative conflict in a way that makes collaborations stronger and the work better.

About the Creators and Host