Commit to your best work (always!)

When Ann Patchett sat down to read through her first draft of The Dutch House, she realized she had made a terrible mistake. A wrong turn, on page 36, sent the entire rest of the novel careening down the wrong path. So what’d she do? Deleted it and started over. Sometimes, committing to doing your very best work means destroying it and going again. In her own words, novelist Ann Patchett shares the story of writing her award-winning novel — from the prolonged period of preparation, and the active defense against distractions, to the advice from friends that she took without a second thought. Plus: hear how she recruited Tom Hanks to read the audiobook.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: It’s not good enough

- Chapter 2: The Spark

- Chapter 3: Preparations

- Chapter 4: Before I start writing

- Chapter 5: Wise to my own lies

- Chapter 6: Just write a paragraph

- Chapter 7: The mistake on page 36

- Chapter 8: Locked out of the house

- Chapter 9: It’s like being saved

- Chapter 10: The audiobook

- Chapter 11: What The Dutch House means to me now

- Chapter 12: The long hallway of life

Transcript:

Commit to your best work (always!)

The Dutch House stands on a table at Parnassus Books, the independent bookstore that Ann Patchett co-founded, in Nashville, Tennessee. Hot tip: If you order Ann Patchett books from Parnassus, they might come to you autographed.

Chapter 1: It’s not good enough

ANN PATCHETT: Every book I have written has been, at that moment in my life, the best book I could write.

If you say to yourself, “I am going to do the best work I am capable of,” then you’re going to know what you’re capable of, and it’s not going to be good enough. You’re going to be disappointed. I disappoint myself every single time I sit down to write, and I forgive myself.

If I could give one thing to other writers: the ability to say, “I’ve done my best work. I wish it was better, I wish I was smarter, I wish I was more talented, but this is the best I can do. And tomorrow I’m going to get up, and I’m going to do it again.”

JUNE COHEN: That’s best-selling author Ann Patchett, and she’s about to tell us the story of writing The Dutch House, her ninth novel.

This is Ann’s specific story of writing a character-driven novel — and throwing away the entire first draft. But the takeaway is universal: Commit to doing your very best work, always, and be honest about it.

As Ann takes us on the journey of writing The Dutch House, you’ll hear how she holds herself to her highest standard, but also forgives herself when she falls short. You’ll learn how she listens carefully to feedback from trusted friends — and always (well, almost always) assumes they’re right. You’ll also learn her time-tested rituals for getting started, staying focused, and being wise to her own lies.

As a bonus, you’ll hear some delicious, previously unheard details about how Tom Hanks came to narrate the audiobook (and, also, who she asked first).

And here’s what you need to know about Ann Patchett, who’s one of the most beloved novelists of our time. In 1992, she wrote her first novel, The Patron Saint of Liars. And in 2001, she published Bel Canto, which won numerous awards, including the Orange Prize for Fiction. Ann is also co-founder of the independent bookstore Parnassus Books, in Nashville, Tennessee.

As for The Dutch House? It’s a novel that explores the bond between two siblings, the house of their childhood, and a past that won’t let them go. It was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2020.

I’m your host June Cohen and on this episode, you’ll hear original music composed for piano and clarinet. For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com.

[Theme music]

Books from Ann Patchett include The Patron Saint of Liars, Bel Canto, The Magician’s Assistant, and Commonwealth.

Chapter 2: The Spark

ANN PATCHETT: I was interviewing Zadie Smith in the middle of her book tour. While we were on stage, she said, “It is an autobiographical novel, but I am not that mother. The mother that I wrote in Swing Time is the mother that I am afraid of being.” And she said, “Writing autobiographical fiction doesn’t mean that you’re writing about what happened to you. It can be writing about the person you are afraid of being.” And it was just like somebody threw the doors open.

At that moment while I was sitting on stage with Zadie, I thought, “I want to write about a bad stepmother.” I’m married to a man who has two children, and I was terrified of being a bad stepmother. Now, my husband is a good bit older than I am, and he had his kids when he was young, and so it’s been a long, long time since I could have done them any harm, but I could tap into that fear. It was just the very first thing that came to the surface.

So that was one very important early part of the story. Another part of it is just feeling like we’re in a country that is so exhaustively in love with wealth, and I wanted to write about a woman who in fact was in love with the poor and with service. What if you suddenly became, through no fault of your own, excruciatingly rich? And you made a decision to walk away from wealth because it did not serve your values?

So, those two mothers in the story were really the beginning point of The Dutch House.

At the Nashville Public Library’s Salon@615, Zadie Smith talks with Ann Patchett about “Swing Time.”

Chapter 3: Preparations

How do you weed out your worst ideas? Forget them before they take root.

ANN PATCHETT: I walk around and think about the book all the time. It just becomes my little invisible friend, and I’m thinking: “Well, they go here.” “Well, how would you not tell your wife that you suddenly had become so rich?” “What kind of a deal would you have to do?” These are the ways the wheels just spin. And in that process, I change my mind again and again and again about what the story is about.

I try not to write things down until I’m pretty far along in the process, because once I start writing things down, I get attached to the ideas.

I like the idea of forgetting things. I like the idea of things just passing through, and the good ideas will stick, and they will keep circling around. The bad ideas will go. And for all I know, the good ideas are going as well — but that’s how life works.

It used to be that the novel lived very nicely in my head as a constant companion. As time goes on and I now have this other thing, which is my career, and all the things that people want me to do, that’s very distracting to daydreaming and working in your head. And I do find more and more that I need to say to myself: “I am now going to go on a walk, and I am going to think about this book.” I have to make it more specific to my hours in the day, which is pathetic that I need to block out time for thinking.

Sometimes I sit down in my office on my meditation cushion — not to meditate, but just to sit as if meditating. I start the timer. I light a candle. I sit down on my little green pouf, and I say to myself: “Now you have 20 minutes to think about your novel. Namaste. Now go ahead, begin.”

JUNE COHEN: Could you hear the smile in Ann’s voice when she blocks time just to think about her novel? It’s one of her secrets to doing her best work, always: She commits to the idea and gives it space, even before she starts writing. And as for when she starts writing? It’s not as soon as you might think.

Chapter 4: Before I start writing

ANN PATCHETT: I’m thinking about time, I’m thinking about narrative, and I’m thinking about names.

I will make a timeline. “This is the opening scene. This is how old the characters are. This is the closing scene. This is how old the characters are. This is the timeframe that I’m working in.”

Then I get more and more specific. “Danny goes to medical school. Danny is in college during Vietnam.”

I certainly knew what the events were that would bring about the end of the book. A huge part of it is when I figure out the narrative: Who is telling the story? Is it an omniscient narrative? Is it a first-person narrative? Is it a limited third-person?

So I thought: “Okay, you abandoned first-person a very, very long time ago.” 1994 was the last time I wrote a first-person book. “Why don’t you go back? Write a first-person book.”

The first thing you have to ask yourself when you have a first-person narrator is: Who is telling this story? Why is this the person telling the story? Is this a person who would actually tell their own story? A lot of people would not. And a lot of people will — with relish.

People will write me letters and say, “Why didn’t Maeve tell the story? It is very much a book about Maeve.” Well, Maeve isn’t the kind of person who would tell her story. Danny is the person who’s going to tell the story.

I think about these people for so long, and I develop their character, their characteristics, their likes, their dislikes, their narrative, their plot, their fate … their death.

And then when I’m all done, I have to name them. And it’s one of the very, very last decisions that I make before I start writing a book. It is so hard to name. Imagine you have a child, and you wait until that child is 20 years old to name it. And you want something that is the embodiment of that person, but you can’t be too obvious, right? You can’t name them Daisy, right? And that’s what it’s like when you’re writing a novel.

So once I’m thinking about time, I’m thinking about narrative, and I’m thinking about names. Then the next thing I know, I’m writing.

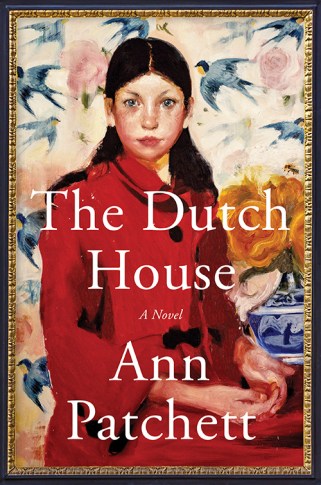

While Ann Patchett decided not to tell the story in Maeve’s voice, she knew Maeve belonged on the book cover. She commissioned artist Noah Saterstrom to paint her portrait (the original now hangs in Ann’s house).

Chapter 5: Wise to my own lies

How do you defend against distractions? Delete them.

ANN PATCHETT: Before I start a novel, there is a process of cleaning out my life. I cannot abide pregnancy and childbirth metaphors around writing, but it is like nesting. Like, I get everything straight, and I start closing down my life — in all sorts of different ways.

I own this bookstore. I get so much mail you cannot believe it. I finally answer every bit of mail that’s on the desk. I clean off my desk and write to the people who have sent me galleys that I will never read and refile the books — whatever it is. My email inbox, there was not a single email left in my inbox. I answered them all. And the ones I did not wish to answer, I deleted, because email is a place to hide.

I know my games. That’s the beautiful part of getting old: I am wise to all of my lies, and I know that if I have a full inbox, I will answer the email rather than write my novel. And because I can’t seem to retrain myself, the way I can handle it is to just answer the damn email. When I look around and say, “Oh, well, I can’t do the important work I was put on this earth to do because of x,” then I need to delete the x.

JUNE COHEN: “Delete the x.” So simple. So honest. And also, so hard. But if you’re going to commit to your best work — always — you have to, as Ann says, get wise to your own lies.

In this PBS NewsHour clip, Ann Patchett offers more advice on how to retrain your attention span. Watch her 3-minute video essay here.

Chapter 6: Just write a paragraph

What if you get stuck, before you even start? Sneak up on the work.

ANN PATCHETT: I’m a very, very bad starter. I’m strong in the middle, and I’m a fantastic finisher, but I’m a terrible starter. Who wants to sit down one morning and say, “Today, I am writing the opening sentence of a project I will be on for, I don’t know, two years or something?”

I have an idea; I have the book all plotted out. But then when I actually start to write it, I think: “I have no idea what I’m doing.” I don’t know how to transfer ideas into writing; that’s always where I get stuck.

And then I sit down one day and say, “Okay, well, this isn’t going to count, but write a paragraph. Go ahead, just write a paragraph. Just throw it away tomorrow. This isn’t the real start.”

And that’s how it starts. I’m sneaking up on my novel. I’m coming in very quietly sideways.

Chapter 7: The mistake on page 36

ANN PATCHETT: I had been having a hard time finishing the novel. A lot of demands, a lot of busy-ness. I was rushing, thinking I can get this done, I can get this next thing done. I finished the novel, and I’m feeling really good about things. And I’m doing my read-through of the book. I was upstairs, laid out flat on the floor of my office with my little green meditation pouf under my head, and it’s great, and it’s great, and it just goes down and down and down as I’m reading it. I’m reading my own novel that I wrote, and I was 10 pages away from the end, and I can’t finish it. It is a disaster. And I’m thinking, “Oh my God, I made a mistake on page 36, and the whole book is on the wrong path.” I just sort of laid there and looked at the ceiling. I knew it was wrecked. I didn’t know how to fix it, and I deleted it.

I went downstairs, and I told Patrick, and he said, “Shouldn’t somebody read it? Shouldn’t I have read it?” I said, “Well, one, it’s gone.” I said, “My only joy at this moment is knowing that you didn’t read it.” Like, “I really want you to love me. I want you to hold on to that memory of me as a really competent novelist.”

People would say to me, “It must be like losing a child.” And I said, “Jesus Christ. It’s like burning a cake. It’s not like losing a child.” You made a cake. It was hard, it was complicated, you left it in the oven too long. It’s burnt. You can slice it in half and eat some of the little fluffy parts out with your fingers over the sink, but you can’t save a burnt cake. You know how to make the cake. Your ingredients are all still out there. You just throw it away, and you make another cake.

Chapter 8: Locked out of the house

How do you start over after a failed first try? Ask a wise friend to point the way.

ANN PATCHETT: It took me months to figure out how to get back in. That was a very miserable period of time. If you’ve ever had the experience of being locked out of your own house, and you walk around, and you look in the windows and you think, “That’s my house, that’s my stuff. I’m on the outside. I’m going to figure out how to get back in the house.” But if you don’t have a key, or a brick, you’re not going to get back in the house. It’s locked. They call it locked for a reason. And that’s what it was like. I would think, “Okay, well, not in first-person this time.” I would write 30 pages. “That’s not right. I’ll try it in Maeve’s point of view. That’s not right. I’ll try it at a different time in their life. That’s not right.”

I dumped that book in August, and it was early November, and Barbara Kingsolver was here. She was doing an event at the store. So one night she said, “Okay, tell me your problems.” And I told her the story of the novel. I told her what I was struggling with. And she said, “Well, I know what you did. You turned right there. That was the wrong turn. The mother doesn’t die. The father doesn’t lie about the mother dying. He tells the truth, and they go from there. Danny doesn’t go to India.”

And as soon as she said that, it was like the tumblers on the locks just went click, click, click, click, click. “Yeah, I can hear you. I can hear what you’re telling me. And I know how to make that work now.” And it was with joy that I took her to the airport the next morning, because then I could rush back and go to work.

So it was the same book, the same characters, the same timeline, the same narrator. But where I turned right on page 38, when I rewrote it, I turned left. And when I got back in, I wrote that book like wildfire.

In this Dec. 2021 virtual conversation, you can see the warmth between old friends Ann Patchett and Barbara Kingsolver. Watch that interview here.

Chapter 9: It’s like being saved

ANN PATCHETT: I was a kid who wanted to turn my homework in and have it be perfect. I wanted my teachers to say, “This is the best homework I’ve ever seen.” And the only way I could figure out how to do that was to have my friends look at my homework. I always want to turn my book in and have my editor say, “Boy, what are they paying me for? There’s just not a thing I can do. This is perfect.” And the way I do that, and I always do that, is by having my smart friends read for me.

Just as I finished the second version, Dutch House 2.0, which I thought was so wildly improved, Jane Hamilton — Jane and I read our books out loud to each other. So I was reading The Dutch House to Jane, and she said, “The first two-thirds of the book are just fantastic, and I love it. And, the last third of the book, it doesn’t work. And this is why, this is what you did. Danny and Maeve were in agreement about their mother.” And Jane said, “There’s no tension, and it’s also just not true.” And the second she said it, I said, “Yeah, right. You’re right. You don’t need to tell me twice.”

When somebody tells me something, I don’t torture myself wondering if they’re right. I know they’re right. It’s like being saved. It’s like somebody saved you from being in an accident. Somebody has saved me from putting out something that is not my best work. Thank you. There’s nothing — there’s no other word. Thank you. There’s no other emotion. There’s not, like, “Ah, I don’t want to do this again. Oh, you’re right. But it would be too hard.” Forget that. Forget that. Time is so precious. I don’t want anybody to read a bad novel of mine. Nothing is more horrifying than that. Nothing comes close to that: putting out a bad book, and nobody told you it was bad.

Chapter 10: The audiobook

How do you make your best work even better? Add someone brilliant, at the top of their game.

ANN PATCHETT: On a complete whim, I asked John Lithgow to record the audiobook. I know John Lithgow a little bit. I just thought he’d be amazing. John Lithgow couldn’t make it work. He could not have been nicer about it. And so I asked Alan Alda, because I’m friends with Alan Alda, who would have been amazing. He would have just been amazing. He really tried. He could not make it work with his schedule. Well, I have one shot left. I know one other famous person.

Just a weird set of events that I kept seeing Tom Hanks. I had blurbed his book, Uncommon Type. Later on, I was asked to interview him. He was interested in opening a bookstore. He comes to Nashville, and we became friends, in the way one becomes friends with a movie star over email. It’s not like we’re vacationing together. I don’t want to overstate it. I wrote to Tom, and I said, “I don’t think you’ll do this, but no pitches, no hits. You don’t try, it’s never going to happen.” And he wrote right back, and he said, “Oh, that sounds like fun. Send me the manuscript, and let me see.” And I did.

And as this all unfolded, I felt sick. It was like I had walked up to somebody and said … Well, it was like I’d walked up to Tom Hanks and said, “Hey, give me a million dollars, will you?” And he said, “Sure!” And then you think, “Oh God, no, I was joking.” I wasn’t joking, but the enormity of the ask did not hit me.

A few days later, he wrote back, and he said, “I love it. I definitely could do it. I just don’t know that I’ll be able to find the time.” And that’s where Sooki came in. I became friends with his assistant, Sooki Raphael, and she made the time. She just rearranged his schedule, and she found four days, and it was enormous.

The audiobook sold a bazillion copies. This is a weird phenomenon, but it really is true: The people who listened to the audiobook, they loved it because of him. And then they went and bought the book. And it also went the other way. People who read the book and then heard how great the audio was downloaded the audio and listened to it. So for the vast majority, I got double sales.

I really felt like I should listen to this audiobook because everybody told me how amazing it was. My iPad somehow was stuck on shuffle. I thought, “What difference does it make? I wrote it, right? I don’t need to follow the plot.” When I was listening to it out of order, Chapter 3, Chapter 12, Epilogue, Introduction, I thought he was hysterically funny. In my mind, The Dutch House is, in so many ways, a funny book. All my books, I believe, are funny, and almost no one else believes that.

He had the bored self-entitlement of Danny, just the obliviousness of Danny, down cold. It was genius. I was doubled-over laughing.

The audiobook is better than the book. And when people hear me say that, they say, “Oh, that’s so self-deprecating. Oh no, it’s not. The book is wonderful.” No, it is, it is better. And the reason that it is better is because The Dutch House is my best work. That was the best novel I could write at that point in my life. The reading of The Dutch House is Tom Hanks’ best work. That’s the best he could do. So you’re putting the very best I have and, on top of that, you are putting the very best Tom Hanks has, and you are making mathematically something so much better than anything I could have done alone, or he could have done alone.

Tom Hanks reads the audiobook for The Dutch House by Ann Patchett. Watch the book trailer here.

Chapter 11: What The Dutch House means to me now

ANN PATCHETT: Nothing. Nothing. And this is the way it goes.

The book that I’m thinking about, the book I’m working on, it is my life. It’s my heart. I care so much, but boy, when I’m done, when I’ve gone through everybody’s edits and all the rewrites and the copy editing, and then I read it three times for page pass proofs, I never think of it again. Never. I do not care. I am a turtle dropping her eggs in the sand and crawling away. I am not thinking, “I wonder how it went for those little turtles.” I don’t care.

Yeah, that’s what it means to me now. Sorry.

Chapter 12: The long hallway of life

ANN PATCHETT: When I was young, I could do a lot of things creatively. I wrote really terrible poems and really terrible stories. I drew, and I painted. I could act. I had an okay singing voice. I was just a very creative person. A lot of kids are like that. There’s nothing special about it. I was a creative kid, but I have a visualization of a long hallway of doors. “What do you want to be when you grow up?” “I want to be a fireman or brain surgeon or an astronaut or a garbageman.” When you’re a child, all the doors are open. And to get older is to close the doors. I’ve always found that there was freedom and peace in closing the doors: “Goodbye to that. I will not do that. I’m not going to be a gymnast. I didn’t start when I was four. It’s too late now for me to be an ice skater, for me to be a cellist, I’m closing the doors, I’m closing the doors.” I treated myself as a piece of topiary. I pruned and pruned and became more focused and more specific.

In between books, I want to see what my life looks like when I am not making art. What happens is my cooking improves. I knit a sweater. I look at my den, and I think, “Should I wallpaper?” Suddenly, the creativity starts to come out in all these different ways. Then I begin to write again, and I’m back to a piece of goat cheese on a slice of toast with maybe some avocado, three meals a day, and I could care less. The house, the world, the life can go to hell.

There are so many people that I know who have that tremendous creative life force that just pours out in every direction. My beloved stepmother, I would put her at the very top of this list — the way she dresses, the way she decorates, there is nothing that woman can’t do. She can hand-paint and fire the tile that she puts in her staircase. She can make unbelievably gorgeous dinner parties for 26 people. It’s just creativity in every direction. I took all that energy, and I put it in one thing, which is long-format fiction.

So many of us don’t do our best work because we think that if we give ourselves over completely to our best work, then we are going to know how good we are, and it’s not going to be good enough. Kids sit down to write, and they hit the delete button. They say, “Oh, that’s not good. The muse isn’t with me. I’m not inspired. I have writer’s block.” None of those things are true. What’s true is: This is what you can do. And if you want to be better, you just have to keep doing it. You have to keep practicing. You have to keep working. You have to keep striving to get better, but right now, today, this is your best work. Deal with it.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Ann for sharing the story of this creative journey with us. And I want to thank each of you for listening. I hope you found things in it that you can bring into your own work.

Maybe it’s the way Ann creates rituals to help her produce her best work — from deleting emails to clearing time to meditate on her novel. Or maybe it’s the way she convenes her friends, and actually listens to their honest critiques. Or possibly, it’s her courage to just totally start over: throwing out an entire first draft — without showing anyone — as if it were just a burnt cake.