How to build your creative vision

Making art is a distillation of all your life experiences – from the half-remembered images from your childhood to your fascination with what’s happening around you right now. Photographer Stephen Wilkes developed his signature Day to Night images to share his passion for how time passes – and soon found that they also helped him explore everything else that interested him: nature, city life, even politics. Learn the backstory behind his famous photo of the 2021 Inauguration as he explains how he developed his signature style – and where to start as you develop your own.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

How to build your creative vision

Stephen Wilkes and his assistant Len Christopher (supported by a team of security and logistics experts) stood on a 40-foot crane in nonstop 35mph winds for more than 12 hours, shooting the images to create this magnificent photo of the 2021 Inauguration. The time scale of the photo moves from right to left, from day to night. In the top right-hand corner, Marine One flies away; at center, a sea of hundreds of thousands of flags represent those lost to Covid in 2020; at right, the evening lights. This photo premiered in National Geographic.

Chapter 1: A window of time

STEPHEN WILKES: When you study a single day, when you watch everything that happens within a window of time, a single space where you just deeply watch everything that comes in or out of that frame, it becomes so enriching because you begin to see narratives you never saw before.

Einstein really describes time as a fabric that sort of gets warped and bent. And really, I see time as a fabric as well, and I’m taking that fabric, and I flatten it into a single two-dimensional photograph, and visually show you how the light rotates, how the color of light changes, and how things change over the course of anywhere from 12 to 36 hours in a single photograph.

I’m not interested in just creating a photograph that is based on a locked-in scale and frame, which has been defined historically by the medium.

Technology has allowed us to build out of frame, to expand the way we see, and with that comes a new way of looking at the world.

This image is from the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, in the Seronera River Valley. Wilkes and his team photographed for 26 hours, from 18 feet in the air, as many different species came to this single watering hole over time. This image originally appeared in National Geographic.

JUNE COHEN: That’s photographer Stephen Wilkes and he’s about to tell us the story of shooting the 2021 U.S. presidential inauguration photo. But the story doesn’t start there. Stephen had been building his signature style called Day to Night for decades, and what you’ll hear in this story is inspiration for anyone building a long-term creative vision. Or anyone wondering how to combine all of their creative inspirations into something cohesive.

As Stephen shares his journey you’ll hear him face challenges that seem like roadblocks but actually became accelerators and you’ll hear him feed his curiosity collecting inspiration from many fields and eventually putting them to use.

And here’ s what you need to know about Stephen’s Day to Night photographs. The way they work is that Stephen shoots thousands of images in a precise location on a single day, then he blends them together in a single image that plays with time and paints with light.

In this episode you’ll hear the story of three photographs. The music you hear is our composer Hil Jaeger playing along with the episode and if you’d like to see visuals as you listen go to sparkandfire.com/daytonight and follow along.

[Theme music]

Chapter 2: Forced to think differently

What do you do when your plans fall apart? You reassemble them – as no one has done before.

STEPHEN WILKES: In 1996, I was working for Life magazine, and they said, “Stephen, could you go to Mexico City and photograph a film that’s being made by Baz Luhrmann called ‘Romeo + Juliet.’”

So I go down to Mexico. They had built this grand ballroom. It was extraordinary set-building. It had three levels, a huge sweeping staircase that came down. If you took your eyes and blocked where the lights were and everything, you’d swear you were in an actual, physical space, that this was some kind of ancient building.

They asked me to do a three-page gatefold, so a very big, wide photograph, to pay homage to these great photographs that were done in the ‘40s of big Hollywood movie sets. Essentially like a massive group shot, the whole cast and crew. We’re talking of over a hundred people in one photograph.

And I had my panoramic cameras. I looked at the set that I was supposed to create a panoramic in. The set was a square. Complete square. I had to think on my feet at that moment, like how do I make this square set into this dynamic panoramic image?

When things don’t go right, it forces you into a space where you actually have to think differently.

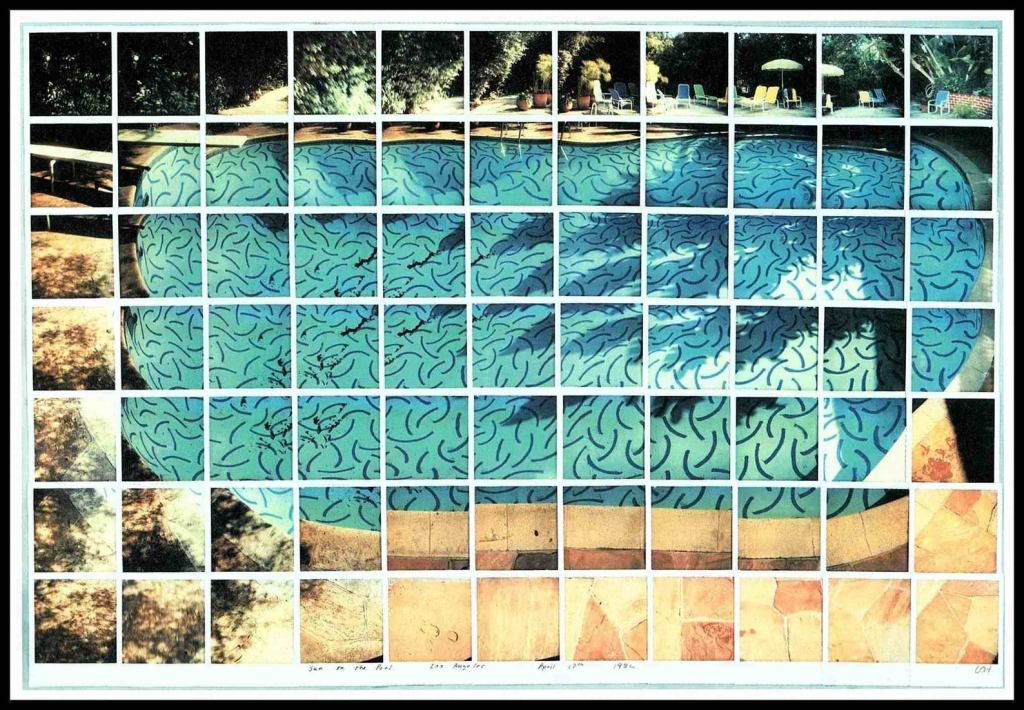

At the time, I was really impressed with the new series of work that David Hockney had created, and they were these photo collages. He was moving a camera through a scene, panning. And then he was, by hand, pasting all these images together, and he was creating almost a fractal-like way of seeing a photograph, the way your eye moves, almost, through a photograph.

Around 1982, painter David Hockney experimented with capturing the passage of time by collaging many Polaroid images together into one Cubist image – like this one of his famous pool. Learn much more about Hockney’s composite Polaroids at the David Hockney Foundation.

Photography has historically been defined by the film size, right? So if you shoot with a 35 millimeter, this is your frame, there’s a lens-to-frame ratio, and that’s what we see. One of the things that was exciting to me about what Hockney was exploring was he was essentially throwing out that. He could expand the vision of what he sees as opposed to what the limitations of the medium were.

This idea of taking the square and opening it up. And I thought, “Wait a second. If I shot 250 images and pan my camera across this entire square, I could take the square and then open it into a panoramic shape.” I’d never done anything like this before. Could this work? If I shot all these different pictures, what would it look like as I paste them together? The only way to test that is to actually shoot pictures and start cutting them together.

In this image you can see the notes that Stephen Wilkes made as he figured out how to make these hundreds of separate images work together – in a world before Photoshop.

So we did an actual test using Polaroids. I shot almost 200 Polaroids to sort of see, is it going to work? Can this actually happen? Can I create this panoramic shape doing this technique? And so I, you know, I went for it.

Finally, the moment of me doing this photograph. I set up my camera. You’ve got Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes in the center of my photograph. As I pan my camera and I was taking all these other pictures, I suddenly saw a reflection of Leonardo and Claire all the way on the right-hand side of my photograph. There was a 25-foot mirror on the set. They were reflecting in the mirror. For that one moment, that one photograph that I took, I just had this thought. I said, “Leonardo and Claire, could you guys just kiss for this one photograph?” And so I had them kiss in the reflection.

I came back to New York and I took these 250 images, I remember, on my studio table. And I, by hand, constructed this entire thing. Then I started to explore this idea that I had a narrative going on within this wide-shaped panoramic. And realized as I finished it, I looked at it, and saw them embracing in the center, kissing in the reflection.

A more refined version of the Romeo + Juliet photo collage that shows the square building in a panoramic frame.

Suddenly I said, “God, that’s so cool. I’m changing time in a photograph. Wait a second. If I could use technology that way, I could create a photograph where I could merge time.”

This gorgeous photo from the Mexico City set of Baz Luhrman’s Romeo + Juliet contains many hidden surprises and small moments. The irregular border of the image is surrounded with white angel wings. This image appeared in Life magazine in 1996.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how Stephen’s fascination with David Hockney unexpectedly led to a breakthrough in his own work. But that wasn’t what drew him to David Hockney; he wasn’t standing in his work for that purpose. Stephen took it in out of curiosity and the work presented itself to him when he needed it.

Chapter 3: Thirteen years later

What do you do when something inspires you? Notice it, hold on to it and wait for it to intersect with your work.

STEPHEN WILKES: I love New York and I photographed for years in New York. But when I first set foot on the High Line, I never saw New York like that before. I could recognize you if you were on the street corner and I could also look up in a building and possibly see you in a window. It had this intimacy and scale in the same breath.

Jody Quon was my editor at New York magazine, and Jody said, “Stephen, you’ve got to make the definitive photograph of the High Line.”

In scouting the location, I could not decide which time of day I liked better. I really love it at noontime when everybody would come out over 10th Avenue and have lunch. But it’s really spooky and cool at night.

Really good, creative ideas I think happen when there’s an intersection. You need one thing, the initial aha moment, that image where time changed in a mirror. There has to be another thing that comes into your orbit. Somehow they intersect and you go, bang, that’s it! I should do this!

I said, “Well, Jody, I have this crazy idea. What happens if I did the entire High Line from the south end going all the way north, day to night. As your eye moves from the left to the right, time changes.” She was like, “Oh my god. Can you do that?” I said, “I don’t know. I can try.”

Stephen’s Day to Night photo of the High Line, taken from atop a crane in touch-and-go conditions, captured the all-day/all-night life of this unique park high above New York’s west side. This photo was shot for New York Magazine

Chapter 4: I’m going to need a crane

How do you accomplish the impossible? Get as creative about your tools as you are about the work.

STEPHEN WILKES: I spent literally about two weeks scouting every rooftop, every balcony I could get my hands on, and nothing could give me the exact view I wanted. And so, I remember calling Jody and saying, “Listen, I’m going to need to get a crane.” She goes, “Why do you do that?” It’s like if you’re going to create a definitive photograph of the High Line, you have to represent what it feels like to be on the High Line.

I need to get intimate and I want to capture the breadth at the same time. I want it to feel like the High Line. So in order to do that, I had to be elevated. I’m going to need to get a crane.

Then the question becomes, well, how high do you get? Well, the higher you get, the wind can affect you. I knew that I wanted to get at least 30, 40 feet high, because I had to get slightly above the High Line to see into it. I remember we drove the crane in position. I found this elevation I liked. My assistant at the time, Brian Lashinsky, we were up in the air, I had another assistant on the ground, and we had a little bucket with rope. And that’s how we get our essentials, if we need water, if we need food. That’s really how we roll. Then I started photographing.

That building we’re looking at, it’s a federal building. So we had the FBI come over to us. They were worried that we were potentially some kind of a threat, because can you imagine them working in their offices and going, “What the hell is that guy doing out there in a crane? Who is that guy? What is he doing? Is he spying on us?” Thank God they didn’t say, “You’ve got to get down.” They didn’t say anything like that.

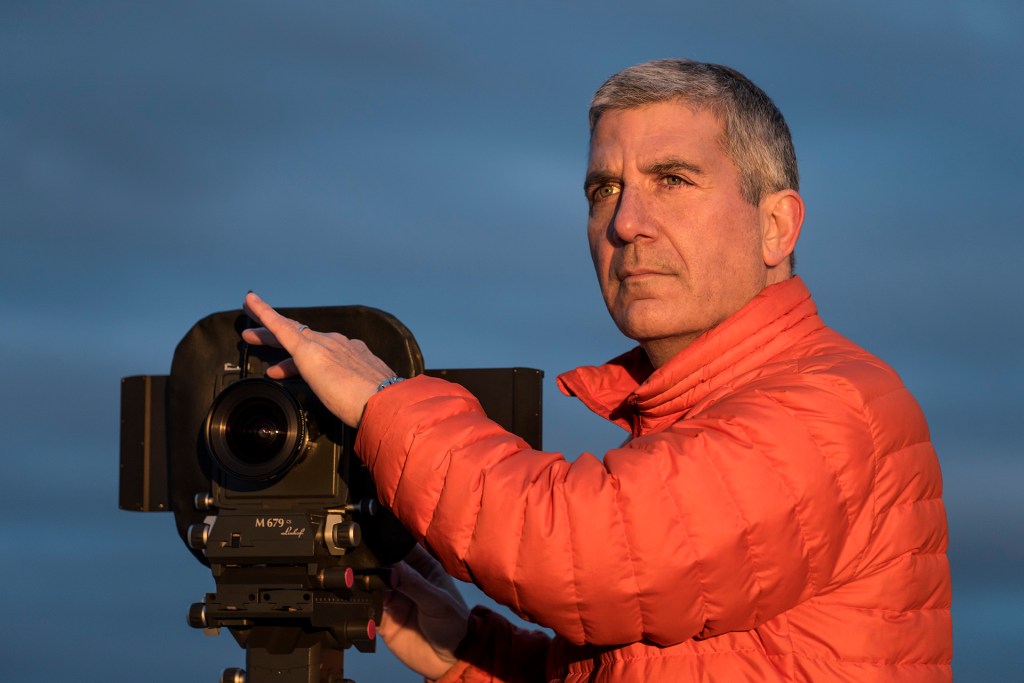

Stephen, on location, just trying to stay warm while shooting for hours. Photo by Chris Janjic

We were up in the air since 4 o’clock in the morning. We got up to 3 o’clock in the afternoon, and suddenly all hell breaks loose – a major thunderstorm, like lightning, full-on crazy torrential downpours. And you cannot be in a metal bucket truck during one of those in New York City. I mean, you know, I could have had my Ben Franklin moment.

And so, we had to come down.

I knew because of what I was doing technically that if I moved my camera at all, we were going to have problems on the execution end. So we dropped lines and we measured exactly what our height was. We tried to minimize any movement so we could get down, get out. All my gear is in there, it was covered up and everything, but still, you have these big humidity changes. The lenses can get fogged. Rain is not a good thing for electronic equipment in general.

Then beyond that, you start reflecting on the fact that, dear God, am I going to get a sunset? Am I going to be able to get up there? Do I have to do this all over again? Then hopefully get back in after the rain passed, and the lightning, and try to get back up to the exact position.

In my brain, I thought, oh, it’s not going to work. There’s no way we’re going to be able to get back to this exact – there’s just no way.

We came back into position. We had the old picture and we shot the new picture.

I shoot into a computer when I do these pictures. So I see them come up on the screen in real time. And you know you’re in the exact position when the frame doesn’t jump.

My assistant, Brian, I swear to God, he dropped it on a dime, and I literally almost started crying, I was so excited that we were able to get back into the same position.

Another New York City scene from the Day to Night series shows Times Square’s nonstop motion. Stephen writes: After trying for a long time to arrange permission to shoot this view I was finally able to photograph in June of 2010. It was a beautiful summer day and I knew there would be many people in Times Square. I had been shooting for approximately 2 hours when the police entered the Square and asked everyone to leave due to a bomb scare. One of the only times I can imagine Times Square being completely void of people happened right in front of my camera!

Chapter 5: Day to Night is born

How do you bring an expansive vision to life? It’s all in the tiny technical details.

STEPHEN WILKES: For Romeo + Juliet, I by hand constructed this entire thing. And then Photoshop was invented and I never had to do it by hand again. Now we could do it seamlessly, using a computer. And that was really the big game-changer for me, was being able to take technology, the tools of technology, and have them integrate with my conceptual ideas. And that’s really how Day to Night was born.

What people don’t realize, what’s so challenging in creating these photographs, is creating a visual harmony between these two very discordant worlds, day and night. It’s very hard to put day and night together and create a visual harmony.

So it’s a combination of how I execute the photographs, what I’m photographing, and the execution on the back end, technically, with my retoucher, how we bring the image together, how it comes to life. I’ve always set up a 35 millimeter camera, and all it does is a time-lapse, that’s all it does for me. And essentially it’s my study guide, and I take it and I go into QuickTime and I can actually see, I can see time move like this. I just see how light moves. And that helps me when I decide how time’s going to move through a photograph.

Every photo in the Day to Night series is arranged along a particular axis, showing a progression from the day side to the night side. This is a carefully considered decision for every image; there are many possible axes for time to flow. Photo by Lenny Christopher

Each photograph generally can take about a month of editing to create a master plate, and then another two months, potentially, by the time we decide on the 50 moments that go seamlessly into the photograph. Sometimes I have less. Sometimes there’s more than that. And all of those moments are literally chosen based on time.

Everything is defined by the time narrative. Once I decide where day begins and night ends, that’s called the vector of time, and I am religious to that vector. So everything moves through the photograph based on where the time vector is.

Imagine if you had a ruler, and you have a pen, you looked at my photograph, and if you drew a diagonal from the bottom left corner all the way to the upper right corner, that line, I call that my Z axis. And if I say to you, time’s going to move from the left corner all the way across to the right, time will travel across the plane of that line. Sometimes I draw the line vertically. That’s called the Y axis. The bottom of the picture is day, and if you move up the frame on a vertical axis, you actually see the night sky happen at the top of the frame. That’s on a Y axis. Sometimes I do an X axis. That’s on the left or the right side. So once I decide where it starts, day to night will happen through that line.

On the High Line, you can see the reflected light of the morning on the windows, and then as you go to the other side, you see that sort of open shade, and then you see the actual streetlights lighting the right side of the building. So that’s where I started to really begin to understand how I could move light and time through a photograph.

As the work began to grow and evolve, I started to realize that I was exploring something on a two-dimensional photograph that was really an exploration in the space-time continuum.

Stephen writes: The lesser flamingos of Africa’s Great Rift Valley thrive in the extreme environment of high-altitude soda lakes, feeding on algal blooms that are toxic to many other creatures. The birds are not migratory but nomadic, traveling from one lake to another, wherever food is plentiful. I shot 17,42 photos over 36 hours from a 30-foot scaffolding, capturing the endless movements of the flamingos and the marabou storks stalking them. This photo appeared in National Geographic.

For me, one of the great joys is most people look at my pictures and they go, “Wow.” They just get wowed by what they’re looking at. And then they go, “Oh my God, time’s changing in this picture.” Like, it’s this complete surprise once they get into the work. At first, they just love it as an image. And then the second level is they discover time is changing in the photograph. That’s really important to me, that it works as a single image.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice the excitement in Stephen’s voice as he talked about vectors and the X axis? Those particular details might not be your thing, but the problem solving passion is what can drive a big vision.

After the break: Inauguration Day. 10 cases of equipment, 200.000 flags, 16 hours spent 40 feet in the air with 35 miles per hour winds.

Chapter 6: The childhood poster

Where does inspiration come from? Everything you choose to take in, even when you don’t remember it.

STEPHEN WILKES: Someone wrote me a letter, and they said, “Mr. Wilkes, your work looks so inspired by the Lumière series, by Magritte.” And he sent me a photograph from the series, these beautiful puffy white clouds and this pale blue sky. And then as your eye moves down, it was nighttime. And the street light was on, and there was this sort of eerie kind of darkness, and just a faint glow of light along the sidewalk that just barely illuminated the scene. It had this strange duality.

I grew up with a poster in my room: the street light at night with the house, and the lights on and the clouds above. The photograph he sent me, that was the poster I grew up with as a kid. So it gave me chills, because I never looked at it like Day and Night as a kid. I just looked at it as this really cool, arresting image. It was overwhelming for me to be able to have somebody literally evoke the memory of my childhood room in that moment. I had not remembered that. And it made me realize, those things that we think in life are somewhat not significant are actually quite significant. And something you live with, a piece of art that you look at daily, how it impacts you in a powerful way, subconsciously how it impacts you.

That’s the power and the beauty of art.

And I say this all the time to students when I teach: So much of what you do as an artist is an absorption of ideas, of things you see, of what you hear, of the things you feel, that translate into your mind’s eye. And those are the things that really drive what you look at and how you look at them. The act of art, in a sense, is almost this beautiful filter that happens. It’s a distillation of all your life experiences. If you want to become a better artist, become a more interesting person.

Rene Magritte painted almost 30 different versions of this image, which blends the closeness and intimacy of night and the wide open blue sky above. Learn more about these paintings in this useful essay from SFMOMA.

Chapter 7: Shoot what you love

How do you arrive at your own distinctive style? Feed your own insatiable hunger.

STEPHEN WILKES: Young photographers say to me, “Well, what do I need in my portfolio? What’s going to get me the job?” And I always say to them: “Look, if you want to do this, find out who you are first. Don’t worry about what you’re looking to sell, define who you are first, feed your soul. And when you do that, you become you. And there’s only one you.”

People ask me, How did you develop your style? The style is in my heart. It’s feeling yourself in a photograph. That’s what style is. That doesn’t happen overnight. You got to work at it, but you don’t get it through just solving other people’s problems.

And so for me, when I see people who want to become photographers and want to do this, I always say to them, shoot what you love, shoot the things that you can’t stop thinking about, shoot the things that make a difference in you and your life. The people who are closest to you, things that are in your orbit that you love, that’s when it comes from within. But if you’re worried about solving someone else’s problem, you’re never going to get to that point. And as much as I love and I do, I love doing commercial work and I do it to the best of my ability and creatively, I give everything I can, but it is different. There’s always a difference between doing your own art versus when you’re solving someone else’s problem.

The world is so rich and it’s so deep. There’s so much to look at. I love looking at something I may have never seen before. It’s about having a childlike enthusiasm to constantly want to learn through your eyes, like see. When the world gets dark and when things are going wrong, for me, the act of shooting, the act of photographing is the ultimate escape. It just makes everything that’s dark go away.

Stephen Wilkes shooting on location. Photo by Chris Janjic

If I’m too comfortable, I’m not working hard enough. And when you have that kind of mentality, you’re setting a sort of an agenda that says you want to be outside your comfort zone. Part of being uncomfortable, it just makes me become hyper present – where I become so focused, so in the zone, while I’m being open to whatever comes into my orbit. One of the reasons the work sort of pivoted from cityscapes – you know, at this part of my life, I’ve been doing this for many, many years. These pictures take enormous amounts of physical work and mental work. And so I look at my life now, and I say, I’ve got a window left to create still as a fertile artist and someone who’s still got his energy. What do I want to say with that time?

I think it starts with curiosity. You have to have this insatiable hunger to look at things and discover things. My work over the years has gone from this voracious appetite to look, to where I’m now driven by purpose to specific issues, core issues that I believe most in, that we need to bring and draw attention on. And I say that curiosity is the car I drive in, but purpose is the fuel in the car. That’s the gas that drives everything.

To be able to put in the hundreds of hours necessary to create a Day to Night photo – the image has to have meaning. Photo by Lenny Christopher

Chapter 8: The Inauguration, 2021

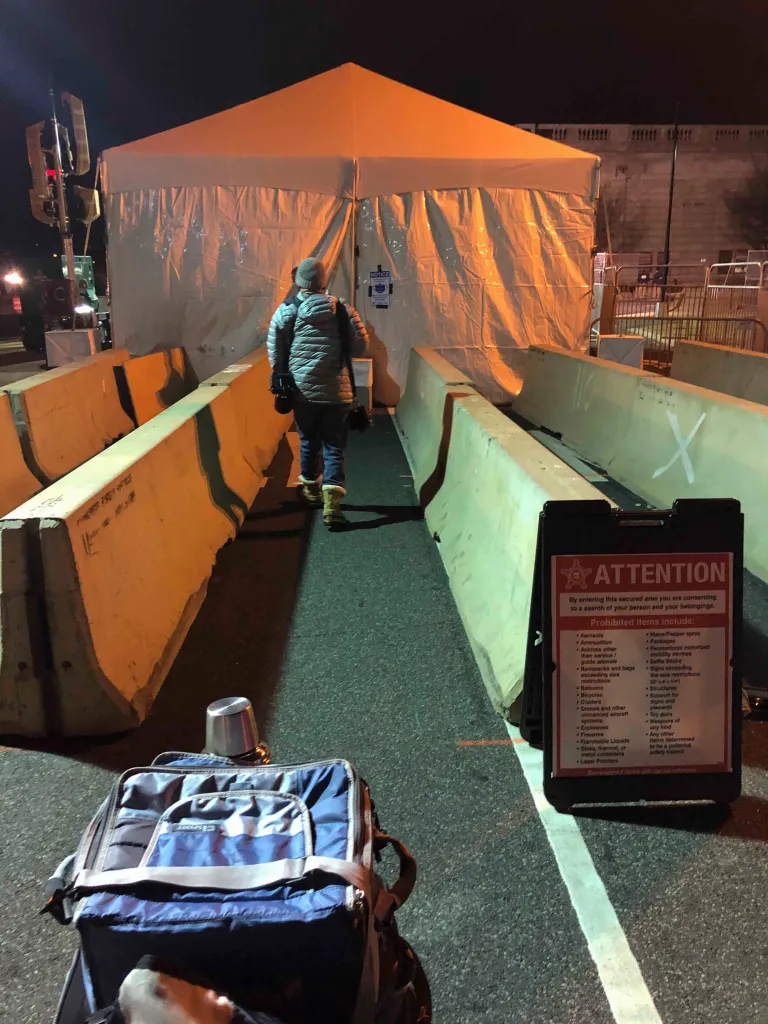

STEPHEN WILKES: I was never a war photographer, but I think for me this was about as close as I ever got to what a war zone looks like, the Green Zone in Iraq for example: that’s how tight Washington was closed down.

I was fortunate enough to get National Geographic behind it. They supported my effort to make this photograph, but I was blessed too, because of the Biden team and their support of my work. They gave me access that virtually nobody has.

Security was tight at the 2021 Inauguration, held on the very site where a violent, armed mob had attacked the US Capitol building. Stephen credits his security detail with making the shoot possible. Photo courtesy the Stephen Wilkes team.

We had a wonderful security detail with me, an ex-Secret Service agent, Tim Price and then of course my assistent Len Christopher. The logistics for me to just get to and from my hotel into the mall area was unlike anything I’d ever had to deal with. We had about 10 cases of equipment, the physicality of getting it in, getting set up, getting the lift truck into position. I was pretty much as far back as you could be looking directly into the Capitol Building.

Stephen writes: Five days before the Obama Inauguration, I received a call from the office of the Inauguration committee that they wanted to meet with me. I happened to be in Washington, DC, and I literally ran over to their offices. I was so excited when they told me I had been granted permission to photograph the inauguration of Barack Obama. When photographing his second inauguration I was positioned in a 50-foot scissor lift centered above the National Mall. The lift truck driver had to be vetted by the Secret Service as did I and my team. They delivered the lift truck on the Saturday before so I could move it into the perfect position. I was situated in the middle with CNN on my right and CBS on my left. It was a bitterly cold day but the light was beautiful, crisp winter light. It was a remarkable sight to see the Mall transform from a quiet nearly empty expanse to a sea bursting with red, white and blue. After shooting from sunrise into sunset, I finally began doing our night exposures. At approximately 6:10pm, I made my second night exposure; 5 minutes later I was being battered by 30mph wind gusts causing the scissor lift to tremble – erasing all possibility of capturing another night exposure (which requires complete stillness). If the wind had started blowing just 5 minutes earlier, I would not have had the photographs for the night portion of the image. I still can’t believe how fortunate I was to capture the night exposure and be able to document such a historic moment.

I did the Obama inauguration and Vice President Biden in 2013. And that was of course 800,000 people-plus that day. So it was an extraordinary moment in history. And instead of a sea of 800,000 people, there was a sea of over 200,000 flags.

But you never know when you get up in the air what the weather’s going to be, right? You just never know.

And if you saw the inauguration, you saw how cold everybody was. I’m 40 feet in the air in a crane for 12 hours, 16 hours. It was brutal. It was windy. If I have more than a 10 mile an hour wind on a good lift truck, it’s really challenging to do what I do. We had a steady 35. I mean, steady. We’re not talking gusts, we’re talking steady 35 mile-an-hour wind. And we were being battered up there.

You have to stay calm and you have to be able to be patient enough to wait for the swaying to stop. It’s almost like you have to time the sway, like I know that, okay, if I’m blowing this way, the Capitol’s going to be too far left, but when it comes back, I know it’s going to be in a certain part.

I’m also thinking about the fact that my weight and my body weight and my position are exactly in the same spot every time I’m trying to shoot.

Posted in front of the Washington Monument, Stephen Wilkes and Lenny Christopher sat on this lift for many, many hours, holding their bodies still in the brisk wind and cold to line up their images perfectly.

I was very lucky that we had the technology to be able to circumvent the huge, and when I say huge, challenges of the wind on that day

Like if you said to me, “Stephen, could you have done this picture 10 years ago?” I’d say, “No, I couldn’t do the picture.”

When we got there at 4:30, 4:45, it was snowing. And then at about 5 it turned to freezing rain. And you just can’t get in a lift truck with that kind of conditions. But suddenly at about 5:30 the winds were blowing so hard that you could see the clouds were starting to move out. And suddenly the darkness was beginning to crack and beginning to open. And suddenly I knew, I said, “Let’s get up, it’s going to happen. We’re going to get a sunrise now.” And so my assistant and I went up, and sure enough the clouds start breaking and you could feel things just starting to happen.

And all of a sudden, sometime around 8 in the morning, I hear this helicopter behind me and it is Marine One. Donald Trump is literally taking off and he flies into my picture as the dark clouds are moving away. He’s leaving.

When the inauguration was going on, it was just magical, puffy clouds, picture perfect.

As the time moves from the right side of the photograph which is day, and then the left side at night I got this incredible sunset where these pink striations in the sky just almost like hot pink. But also we got the memorial lights that were created for the memorial to all the people who died from COVID.

The photograph goes from darkness to light. And I think it will be a photograph I hope everybody should feel good about and celebrate and realize that democracy survived, that we survived and that we will get past this pandemic and everything else. So it’s a picture about hope.

As the sky cleared, Stephen’s team realized they could indeed get the shots they needed that day. With their crane backed up as far as it could go, backed against the Washington Monument, they had an unmatched field of vision across the Mall

Chapter 9: A single day

STEPHEN WILKES: What I think about a lot is, how these photographs may represent our world 50 or 100 years from now. I think about what will be of the human race a hundred years from now, where will we be, are we going to still be here? Is the planet still going to be survivable at that point? They are windows into the way we live at this moment in time.

So in a strange way, these pictures for me have always put a face on time. I do think about time. I think about how precious every day is, because of the observation I experienced in making these photographs and of all the things that can happen in a day. Sometimes we don’t think in those terms of a day, a single day. We think of our days more like in months and in years, like, Oh, I remember when you were this big as a baby, and now you’re a grown man or a grown woman. I just look at the single day as this study of time.

I need a lot of alignment of the stars to make these pictures. And you know, they don’t come back and do the Inauguration for you again the next day because the sky wasn’t right, or the winds weren’t cooperating.

So much luck involved, like a winemaker almost. I could have the greatest season, pick the grapes, I put everything together in the barrel and hope the oak blends. It is science, but it’s also a bit of magic. There’s just certain things I just don’t have control over. I just put myself out there, I try to stay positive. And most importantly, I try to stay present because when you’re documenting history, you have to be present.

Stephen Wilkes taking an image from the ground at the 2021 Inauguration, across the field of flags. Photo courtesy of the Stephen Wilkes team.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Stephen for sharing the story of his creative journey. And I want to thank each of you for listening, I hope you found things you can bring in it your own work.

Whether it’s the way Stephen constantly fed his curiosity and waited years sometimes to find the intersection with his work. Or it might be the way he lit up at the tiny technical details that brought his work to life.

It might just be the way Stephen approached each big setback with a mindset of solutions, solutions that just might propel his vision even further. Or it might just be the way he embraces teamwork and always trusts that when he is stuck in a crane in the rain he can lower a bucket and something he needs will come back up.