Transcript

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

5 ways to get creatively unstuck

Patton Oswalt in his 2020 standup special “I Love Everything.” Image: Netflix

PATTON OSWALT: I get stuck all the time. Sometimes you have to play hard-to-get with these things. If you are begging for it, and being needy about it, the idea won’t come forward. Sometimes you have to walk away. Then the idea will be like “wait a minute,” and then it will come after you.

CHRIS MCLEOD: That’s comedian Patton Oswalt, giving us a tease of his best strategy for getting unstuck. You’ll hear it in full a bit later.

And in fact, you’re going to hear from 5 different creatives in 5 different fields offering 5 different strategies for getting creatively unstuck.

I’m Chris McLeod, the Executive Producer of Spark and Fire. I spend most of my time editing our guests’ stories and shaping them into the episodes you hear. Along the way, I absorb a lot of wisdom that I get to carry into my own creative practice.

There are so many inspiring moments of brilliance, but what honestly sticks with me the most are the moments of struggle.

For example, there’s usually a moment when our hero gets stuck along the way. At the beginning of the journey, they feel inspired and confident, but then they find themselves at a dead end — or lost in the forest.

Well, today on Spark & Fire, we’ll be a fly on the wall as these creators rediscover their inspiration. So we can hit our own stuckness head on. Here are five ways to get unstuck.

Our first strategy takes on a kind of stuckness that we’re all familiar with. It’s the kind when you just don’t know what to do next. Maybe you’ve been staring at the screen for a little too long. Maybe your last few ideas just didn’t work.

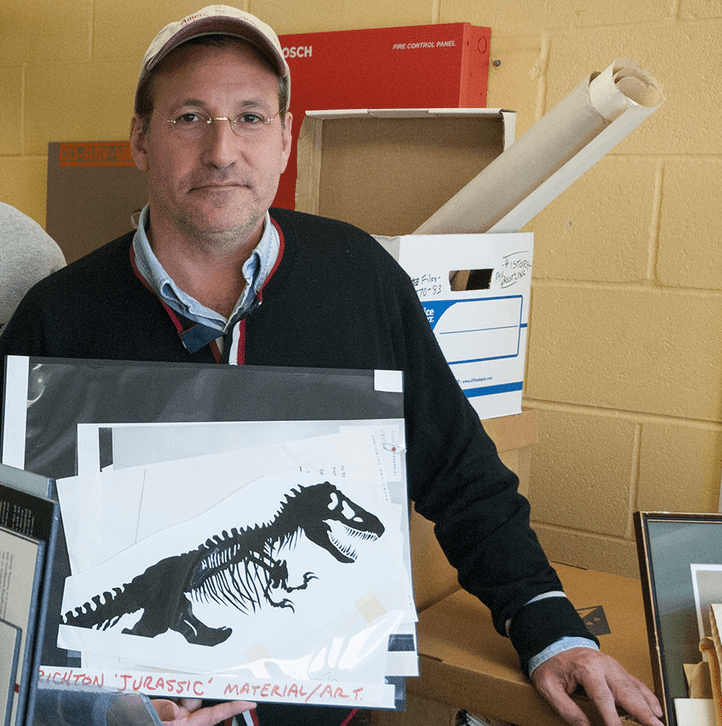

Legendary book designer Chip Kidd knows how to help. In Chip’s episode, he tells the story of designing the cover of Jurassic Park. And he also offers a brilliantly simple method for getting unstuck.

Chip Kidd holds his original drawing for the cover of Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park. Photo: Wilson Hutton, Penn State University Libraries

Strategy 1: Do something else

CHIP KIDD: If you get stuck, if you’re hitting your head against the wall, you’ve been working on this particular project too long and concentrating on it, give yourself a break from it. Give yourself a break from it, and go do something else, because your subconscious is still going to be working on whatever it was that was giving you trouble.

I love to do crossword puzzles because it helps me to think conceptually. My favorite example, the clue was — and I’m just going to spell it out for you — A N-U-M-B-E-R of people. Okay? A number of people. And the answer is: ANESTHESIA because it’s not a number of people, it is a numb-er of people.

And that to me is the magic of a really good crossword clue and answer, because it forces you to consider language in a different way. So, somehow that helps me to design book covers.

CHRIS McLEOD: I love this story because it runs so counter to conventional wisdom. Chip says that to get unstuck, you should stop working, and do something else. Then, when you come back, your subconscious will have done the heavy lifting, and you’ll see it in a new way.

The second strategy is from comedian Patton Oswalt whose episode, which comes out next week, tells the story of 2 Netflix specials he created.

Patton’s strategy also tells you to walk away from your project when you feel stuck — but with a different motive.

Strategy 2: Play hard to get

PATTON OSWALT: I get stuck all the time. Sometimes the hours I carve out to try to write or create something new, a big chunk of that is spent not doing anything. It’s spent staring into space and waiting for the inspiration to hit. Sometimes my strategy is to push through. Sometimes my strategy is to fake it. I put a placeholder idea there in the writing, in the screenplay, in the joke, and hope that it will fill in later in context if I just keep writing. Sometimes you have to play hard-to-get with these things, not be anxiously hanging out there, hat in hand, hoping that you’ll get inspired. It will inspire you. The idea that’s in your head, if you are begging it and being needy about it coming forward, the idea won’t come forward. Sometimes you have to walk away, and then let it chase after you.

So if you go, “I’m going to go for a walk. I’m going to watch a movie. I got other stuff I got to do,” then the idea will be like, “Wait a minute.” Then it will come after you. It’s: you play hard-to-get with yourself. There’s things I like to do every day, keeping the house clean and little rituals. But if I’m off doing those, the muses look at me like, “Well, he’s occupied, and we’ll go find someone else.” You have to sort of sit still, so the muses can find you because the muses are circling all over the place.

I try to meditate twice a day for 20 minutes each session, and I try my best to have a 20-minute block where I do not have any thoughts. It gives me the breathing space to be creative and to not get anxious and self-conscious of all the mundane things. “Oh, well, I’ve got to return that email. I’ve got to get some new shoes.” It’s just, “I’m showing up.” It’s a struggle. Some days, I don’t manage to do it, but on the days that I do, I sit, and I let the muses go, “Okay, he’s not going anywhere. Let’s sit down.”

I’m literally anthropomorphizing creativity, but it helps me to get to where I got to go. That’s a crude way to say it, but you got to get yourself there, and whatever way it takes to get yourself there, it’s okay.

CHRIS McLEOD: What I love about this strategy is it removes the feelings of shame and doubt so many of us feel when we’re stuck. It’s like, “If brilliant ideas aren’t coming, there must be something wrong with me right?” But Patton is saying: “That’s not how it works at all. It’s OK to give myself space. Let the idea chase after me for a while.”

Our third strategy comes from a moment when the entire world was stuck. On our episode with Kamilah Forbes, who adapted the book Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates into a stage production, Kamilah was forced to shut the tour down when Covid hit in 2020.

Then, after the murder of George Floyd, Kamilah, Ta-Nehisi, and the entire team knew that this work, which had helped galvanize the Black Lives Matter movement, had to be a part of the national conversation. But in order to bring this work back, they would have to think about it in a new way.

Apollo Theater executive producer Kamilah Forbes, with actor Marc Bamuthi Joseph in the background, working on the set of the HBO film Between the World and Me, filmed during the pandemic.

Strategy 3: Change course, and start again

KAMILAH FORBES: The play was also going to tour. But then COVID happened.

Myself and a bunch of friends — Ta-Nehisi, Kenyatta Matthews, and Susan Kelechi, it was a bunch of other people — we would meet on Saturday nights for game night. We’d play Scattergories. It was literally our only social interaction with people, on Zoom during the quarantine.

It was that Saturday night. Everyone had CNN, MSNBC on in the background, and we never got to game-playing that day. It was the protest around George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

We just talked about what’s happening in the world. And watching the news footage, and from every city you would see, “Wow, okay, LA. Okay, Chicago, New York.” There was a side comment like, “God, we should be doing the play right now.”

How can we be in this conversation? How can we use our art to really further propel this conversation? We saw that his book had resurfaced on every single reading list every single week, as people were at home, trying to process what is happening in the world. Between the World and Me just became another topic of conversation again. We really began exploring, “well, how do we get this out? Let’s remount this. Let’s do that now. We obviously can’t do the play. We obviously can’t gather people in the same room.”

Then we said, “Well let’s make a film.”

CHRIS McLEOD: To get unstuck, sometimes you have to accept your limitations, reorient, and start again. Kamilah had to accept the fact that putting on a live show wasn’t an option. She couldn’t do anything about Covid, but what could she do? Start over. Make a film instead.

Our next strategy comes from legendary composer, Stephen Schwartz. On his episode, Stephen tells the story of writing the music and lyrics for the hit Broadway musical, Wicked. His strategy for getting unstuck is staggeringly simple.

Composer Stephen Schwartz learned when to put his inner editor back in the cupboard. Photo: Nathan Johnson

Strategy 4: Keep your inner editor at bay

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: All artists get stuck. But I have learned the secret to how to get unstuck. And it’s very simple. And I will tell you the story of how I came to learn this. I was working on one of the songs on Hunchback of Notre Dame for Disney, and I was having that sort of cliche experience of writing things out and then crumpling up the paper and throwing it on the floor. And I just was getting nowhere. And I happened to have a conversation with a wonderful writer named John Bucchino. I was kind of whining to him about how stuck I was. And he simply said, “Oh, well, you’re just being the editor too soon.”

And I realized that when we do any kind of creative work, we’re constantly switching invisible hats. Sometimes we are the writer, who is just putting stuff out there without judgment. And sometimes we are the editor, who is evaluating what’s out there and making choices. If the editor shows up too soon, then you’re stuck, then you have writer’s block because you just judge everything prematurely.

When to become the editor is an instinct. When you have enough raw material, that you can begin to judge it, you can begin to assemble it, you can begin to make choices. But it’s so easy for that editor to show up too early.

Put the editor back into his or her little cubby until it’s time for him or her to show up.

What I have to do when I get stuck is get out of the way and just allow the writer to just do terrible work, if that’s what it takes at first.

It’s sort of like pump-priming out on the farm (where I never lived), where they’d have to get water from the well. Someone would go and they would just put the pump handle up and down and up and down, and nothing would come out for a long time. And then kind of brown, horrible sludge would come out. But then eventually the water would come gushing out.

CHRIS McLEOD: Knowing when to put that invisible editor hat on is not always obvious, but if you’re stuck, there’s a good chance you’ve put it on too soon. Just keep priming the pump until you get unstuck. The inner editor will have to wait their own turn.

Our final strategy is for the moments when an entire team is stuck. Every individual comes with their own experience, preference, and taste. And this is a good thing! It’s why we work together, but sometimes creating work that everyone can get behind is easier said than done.

To know how to approach these moments, we turn to writer and filmmaker, Kemp Powers. On our episode with Kemp, he told us the story of co-writing and co-directing the Pixar movie, Soul.

We come in as Kemp is telling us about the scene in the movie that means the most to him — the scene in the barbershop.

This rendering from Soul shows the main character, Joe Gardner, in a barbershop. It’s a scene that, writer/director Kemp Powers recalls, “might be one of the two or three most reworked and rewritten scenes in the entire film. I rewrote it so, so many times.” Image courtesy Pixar.

Strategy 5: Look for the note behind the note

KEMP POWERS: The barber sequence might be one of the two or three most reworked and rewritten scenes in the entire film. I rewrote it so, so, many times. It was easy to make it incredibly entertaining. It was easy to make it really, really culturally specific, but then there would just be more and more questions about whether it belonged there.

I really was committed to like, “Oh man, this guy, he needs to pass through authentically Black spaces,” as I call them. And there’s no more authentically Black space in the Black community than the barbershop. It was really important that we try to represent that in the film. It was important to me.

We had to figure it out.

People would say that they weren’t sure why, but the barber scene felt like a double beat. It felt like what we were learning about Joe or what Joe was learning about himself in that moment, it felt like he should know that already. This scene has to accomplish those goals better than anywhere else in the entire film.

There’s this expression called, “the note behind the note.” Sometimes people will give you a note, and the note doesn’t really make sense. They aren’t able to articulate specifically what the problem is. But the fact that it’s bumping for them means that there’s something that needs to be addressed, so it’s up to you to find the note behind the note that they’re giving you.

That made us have to go back through and look at earlier parts of the film.

There was a scene earlier in the film: Joe had a downstairs neighbor, Natalia, she spoke almost no English whatsoever. But Joe had a bit of a relationship with her.

They realized that in Natalia’s early days she was actually a circus performer, and that she trained bears with her husband. It was this really sweet reveal that this little old lady had this whole glorious life that Joe knew nothing about. That was the source of the double beat note.

The barbershop was replicating a different version of that beat — that ultimately ended up being cut.

The thing about the Natalia beat that seemed to not be as strong as the Dez, the barber beat was that Joe would’ve never called Natalia his friend.

The thing about a barbershop is often the relationship you have with your barber is going to be the longest relationship you have with anyone in your life, other than your wife or children, sometimes longer than either. I figured: here’s a guy who would know the main character. In fact, here’s a guy who might know things about the main character that the main character doesn’t know about himself.

He had never so much as asked his supposed friend a single thing about his personal life in probably 15 years. To me, that was a way more profound discovery for Joe to make, and it would spark a greater turn in Joe as a character.

CHRIS McLEOD: When working as a part of a team, learning how to look for the note behind the note is a game changer. When our teammates flag that one of our beloved ideas isn’t quite working, there’s usually a reason. It’s time to look for the note behind the note.

It’s a strategy that has become essential on the Spark & Fire team. When my teammates don’t yet see how brilliant one of my ideas is, if I find the note behind their note, and make it work for everyone, the end result is better 100% of the time.

We hope you enjoyed this episode of Spark & Fire, and found strategies that you can bring into your own creative practice. From Chip Kidd we learned that sometimes you need to stop beating your head against the wall, and do something else (like a crossword puzzle). There was Patton Oswalt’s strategy of letting the muses chase after you. Like Kamiliah Forbes, sometimes we have to change course, and start over. From Steven Schwartz, we learned not to put the editor hat on too early. Or like Kemp Powers, sometimes you have to look for the note behind the note from your collaborators.

Whatever you took away from this episode, we hope it becomes a regular part of your own creative work — to unlock your creativity, and get unstuck.