How to begin

How do you move past that “wobbly moment” in your creative journey? Just move. From the moment she heard about it, Susan Orlean knew she had to tell the story of “The Orchid Thief” – a wild, true story of obsession set in the swamps of Florida. But somewhere deep in the telling, she risks losing her own footing. Spark & Fire follows Susan as she pursues the story that “set her brain on fire,” pushing past a creative crisis to write the magazine article and then book that in turn inspired the film “Adaptation.” She tells her story in her own incisive, honest and very funny words — with insider details you haven’t heard, and actionable advice for anyone at any stage of their creative journey.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Obsession

- Chapter 2: The Spark

- Chapter 3: The wobbly moment

- Chapter 4: The momentum begins

- Chapter 5: Into the swamp

- Chapter 6: I think it’s a book

- Chapter 7: Where do I begin?

- Chapter 8: Down the rabbit hole

- Chapter 9: Index cards spread across the floor

- Chapter 10: Back into the swamp

- Chapter 11: The deep end

- Chapter 12: Meryl Streep appeared on the screen

- Chapter 13: Abandon an obsession

Transcript:

How to begin

Chapter 1: Obsession

SUSAN ORLEAN: John Laroche, to begin with, was this truly odd specimen. He was a serial monogamist. He became fixated on something, whatever it was — fossils, old mirrors, orchids — just devouring it, devoting himself to it, being completely focused on it. Had this desire to own every possible example of this thing. And then walking away from it. That was the part of it that I found baffling. I thought of myself as somebody who was completely the opposite. I thought I will never give up something that I loved as much as he loves these things. I would never just abandon an obsession.

JUNE COHEN: That’s Susan Orlean, and she’s about to tell us the story of writing The Orchid Thief, which began as an article in The New Yorker, evolved into a best-selling non-fiction book, and was later adapted into the movie Adaptation starring Nicholas Cage and Meryl Streep.

But Susan’s story of writing the book isn’t just for writers. It’s for any creative who’s figuring out how to begin – not just once, but over and over in the course of a project.

As Susan takes us on this creative journey, you’ll hear her find an unlikely idea and champion it. You’ll hear her push past the inevitable doubts and setbacks. And you’ll hear her find her footing again and again, as the project grows in scope and scale.

And here’s what you need to know about the book. The Orchid Thief was a true story of a man, John Laroche, and his quest to find rare orchids – especially, the ghost orchid. It’s a genre-defying book about many things, including obsession.

The original music you hear is our composer Ryan Holliday, who’s playing along with the story. For visuals while you’re listening — go to sparkandfire.com/orchidthief.

[Theme music]

Chapter 2: The Spark

Where do you find a new idea? The place you didn’t expect.

SUSAN ORLEAN: So I was rifling around in the seat pocket on a plane, something I don’t necessarily recommend that anybody ever do, because you never know what you’re going to find. And someone had left a copy of the Miami Herald. I thought, “All right, I’m going to read the Miami Herald.” My eye fell on a headline that said, “Local nurserymen and group of Seminoles arrested with rare orchids.” I mean, who isn’t going to read that story?

It described an arrest in the Fakahatchee Strand — a place I’d never heard of — which was a state preserve, of this local man, John Laroche, who had a crew of three men with him, who happened to be members of the Seminole Tribe, and they were arrested with six pillowcases full of rare orchids. My brain was on fire. I didn’t know anything about orchids. I didn’t know orchids grew wild in Florida. I had no idea why anyone would steal orchids. My thought is, if you wanted an orchid, you went to Home Depot and bought them.

Many stories have a singular question. This had so many questions: What was the Fakahatchee Strand? Why would you collect orchids? Why did he have, in particular, a crew of Seminole men with him?

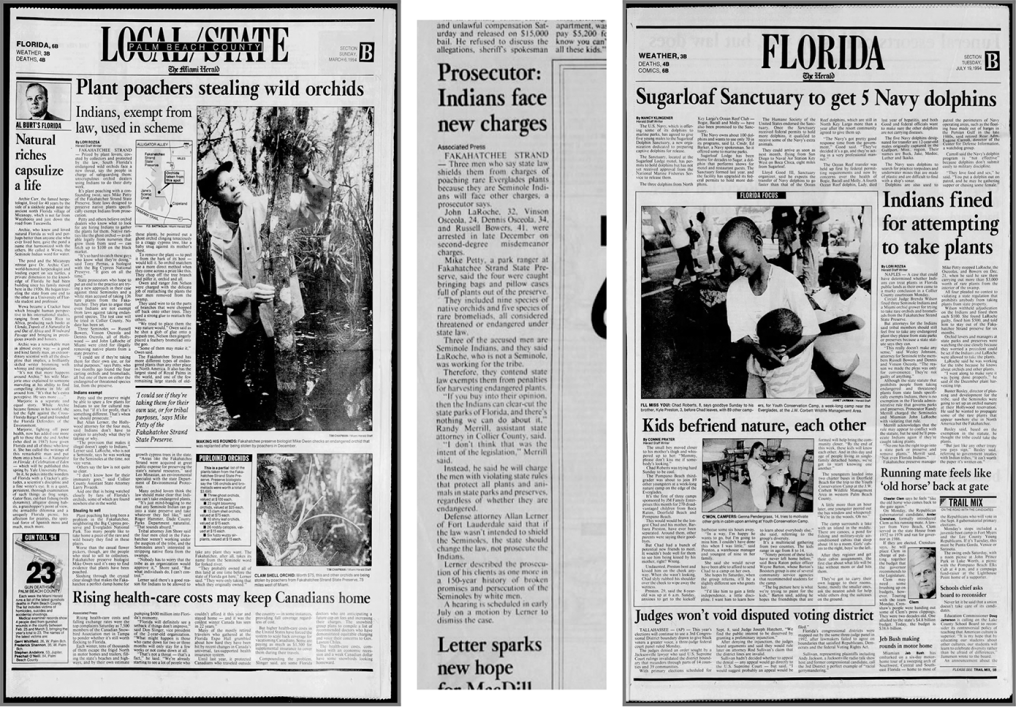

In 1994, the story of orchid thefts in the Fakahatchee Strand played out across the pages of the Miami Herald, in stories by journalist Lori Rozsa and others that track the thefs and the subsequent court case. Susan’s original newspaper clipping is long gone, she told us.

It’s the feeling that a door just opened onto a world that I didn’t even know existed and I thought, “I need to know more.”

The minute the plane landed, I could barely stand waiting for the flight to end. I busted into the office at the New Yorker. I had torn that story out of the newspaper, so I had this frayed little piece of newsprint in my hand. I went to my editor, Tina Brown, and I said, “You’ve got to look at this, and I’ve got to do this story.” She had no interest either in orchids or toothless men with pillowcases of flowers. This was not her sort of subject.

I mean, she was asking the legitimate question, which is, “Why is this an interesting story? I’ll trust you, but you have to convince me.” I think she responded to my intense curiosity, just: “This is so weird. I need to know the answer to why this happened.”

To her credit, even though I didn’t know what it was that I was pursuing, she said, “Go ahead.”

Chapter 3: The wobbly moment

How do you move past your own doubt? Sometimes you need an external push.

SUSAN ORLEAN: I left for Florida a few days later. I probably got back on the same plane that I had just flown back to New York on.

This is always the wobbly moment for me. I begin first with this enormous amount of confidence, this feeling that this is the most interesting story ever in the history of the world. Moments later, jumping on the plane, settling in, I have the second wave of emotion, which is terror.

That terror really is a two-headed monster. It’s both my doubts about the story and my doubt about whether I can tell it. I always try to remind myself that I go through this every time I write anything, and that it’s a natural part of the process.

Creativity is dependent in huge proportion on confidence.

There are times when you need the external push. The fact is the New Yorker bought me a plane ticket, and paid for my hotel room. I arrived in Florida and unpacked my bags and sat in my hotel room, thinking: “I said I was going to do it, so I better do it.”

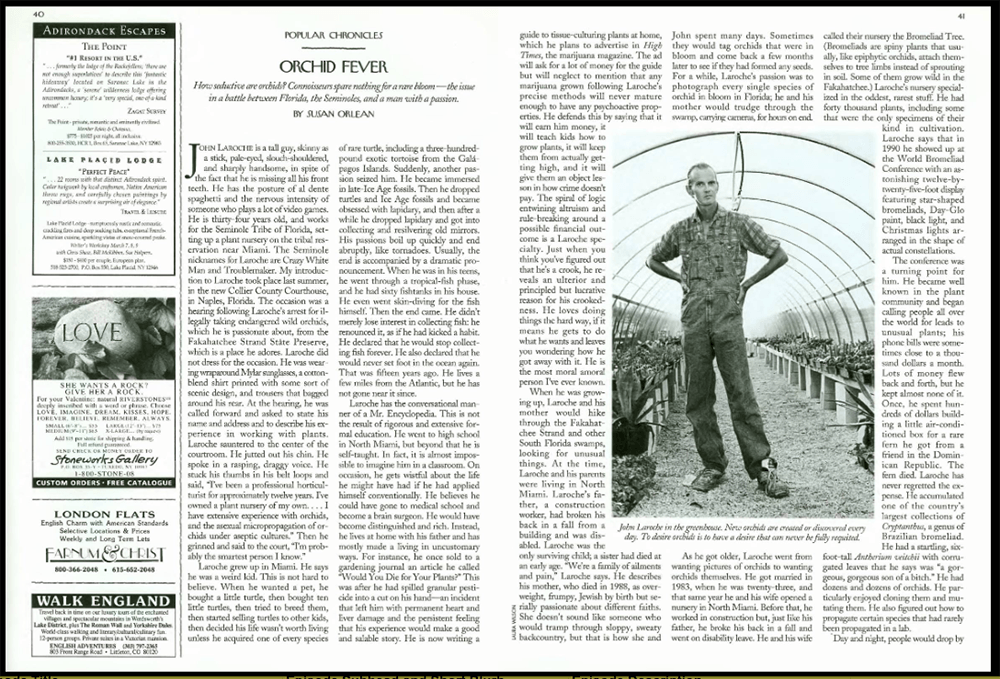

The opening spread to “Orchid Fever,” Susan Orlean’s New Yorker story about the orchid thief, published January 23, 1995.

Chapter 4: The momentum begins

How do you really get started? You stop worrying and start working.

SUSAN ORLEAN: The plane landed in the blistering, suffocating heat of Miami. This was a soaking wet, humid, hot day, where everything felt encased in cotton. The Naples courthouse is made of white stone, and it has a somber quality. I went into the courtroom, like everything in Florida, it was air conditioned to the point that your teeth were chattering. So the room had these rows of dark wooden seats, what almost appear to be church pews, and people were just scattered among them.

I sat toward the back on the left side of the courtroom, trying to angle myself so that I could get a better look. There was John Laroche sitting up in the front of the courtroom with his three compatriots. And John Laroche was the most eccentric imaginable person. He had made no effort to present himself to the court. Everyone else is wearing, despite the humidity, a crisp business suit and tie and white shirts and polished shoes, and John Laroche was wearing a dirty t-shirt, baggy torn gardening pants, and a completely sweat-stained baseball cap.

The judge called him to speak. I heard his grand scheme for propagating these rare orchids and becoming a billionaire. The judge asked him what he did for a living, and he began spooling out this list of accomplishments, which he capped off by saying, “To be honest, your honor, I’m the smartest person I know.” To me, that was it. I thought, I’ve got to write about this guy. His confidence and swagger was so extraordinary. I was immediately in his thrall.

When the hearing was over and the judge dismissed everybody, I wandered out into the parking lot, and I was trying to think of what I would do first for my reporting. And lo and behold, John Laroche comes snaking out of the building. I went up to him and introduced myself. Sometimes people say, “Look, no, I don’t want to talk. Talk to my lawyer.” Or they just push you off, and it can be very discouraging.

In this case, he began just monologuing about how he had been screwed, that the law was unfair, that he was going to take this to the Supreme Court, and he didn’t stop talking. He just kept going and going, and I was writing furiously. I asked him if he would show me the Fakahatchee Strand, and he, between drags of a cigarette, said, “Yeah, of course.” From that point on, I was off and running. I mean, I never looked back.

That’s probably the moment where the switch flips. You begin the work and suddenly you’re immersed in this fascinating world, and the momentum begins.

Fakahatchee Swamp foliage. Image from Big Cypress National Preserve.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice that by the time Susan mentions that the switch had flipped, her switch had already flipped. You could hear in her voice that she moved past the wobbly moment. And this is so often how it goes in creative work. When you stop worrying, and start working – the momentum begins.

Chapter 5: Into the swamp

SUSAN ORLEAN: I was in the middle of the Fakahatchee Strand. It’s a classic swamp, just thick with underbrush and trees and bushes and water that goes from ankle deep to chest high. It’s so thickly overgrown that when you’re in the middle of the swamp, it’s very dark and very quiet. It’s just still. Still enough that it’s frightening. The stump that you’re pushing with your foot as you walk forward, you imagine might be an alligator. You won’t know until it’s too late.

I convinced myself when I started working on the story that, of course, it was essential in order to write this, that I see a ghost orchid. Ghost orchids are evanescent. They bloom very briefly. You might walk past many ghost orchids and none of them are blooming. I needed to see one blooming to see what was so magical about this particular flower. This was the great prize that Laroche had been after. This was the holy grail, the entire story revolved around this single special orchid. I had to see it.

But the thing about swamps is they have a kind of repetitiveness of plant life, and there’s pennywort everywhere and the same scrubby trees and the same fallen logs. So it’s very easy to get lost.

Chapter 6: I think it’s a book

What do you do when you don’t want to stop? You find a way to begin a new chapter.

SUSAN ORLEAN: Many times when I write a story, I feel satisfied. I’ve explored it, I’ve said everything I want to say, more or less, and I feel complete. I feel ready to release it into the world and move on to whatever I’m doing next. In this case, I didn’t.

I felt strongly that each element of the story needed to be expanded upon. Each one felt like I needed to learn more. I felt this urgent desire to peel more layers off the onion.

The story had not yet come out in the New Yorker. I went to my agent, and I said, “I know this sounds crazy, but I think it’s a book.” A book about this toothless, eccentric, who has a plan for world domination through orchid growing. I have to say it probably didn’t sound like a very promising topic.

His jaw dropped a little, and then he said, “Well, if you really think it’s a book, go ahead.”

There’s a buzz that you can sense that a story clicked. And the story just clicked. On Monday when the story came out, what really surprised me was the number of people who were fascinated by Laroche and saw him as this iconic antihero. And also as someone who embodied a version of passion that many people could relate to. This monomania, the sense that you organize your life around a particular pursuit. I wasn’t really sure whether that would translate to the reader. It did in a way that I couldn’t have even anticipated.

Chapter 7: Where do I begin?

What do you do if you don’t know the answers? Start asking questions. And stay with it.

SUSAN ORLEAN: I was revved up, excited, thrilled that I had the book contract, gathered up my fresh pile of reporters notebooks and pens. Flying down to Florida, I remember arriving, unpacking, going to sleep, waking up in the morning, and not having any idea of where to begin. What do I do? Where do I begin? How do I begin?

What is this even about? How do I get to what it’s about? There’s no clear roadmap.

At first, I thought, “Oh, this is really easy. I’ll just kind of add to what I’ve already written,” but that’s not the way it works with books. It has challenges that are geometrically increased. It’s not just a mathematical addition of pages, it’s a geometry of change.

It’s very different to tell someone a story that might take them 20 minutes or 30 minutes to listen to, versus a 300 page story that needs to have arcs, and valleys, and a set of characters who are sustained. It has to have momentum. It has to have a cumulative effect. I think a reader expects to feel by the end of the book that they have achieved something. They’ve gone somewhere.

This incident, what made this thing happen? What brought this man John Laroche and these three Seminole men together in the Fakahatchee Strand with a pillowcase full of orchids?

It’s a very focused question that I realize I can’t answer without context. What I was needing to do was to pry apart the elements of that incident and examine each one.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice the tone in Susan’s voice when she asked: “What is this even about?” It’s as if she’s channeling the angst of every one of us whoever found themselves inside the creative fog, feeling their way forward. For Susan, she made her way by asking questions and answering them. And that might work for you as well. But it might be enough to know: Every creative loses their way … and then finds it again.

After the break: Susan realizes her entire career is at stake.

Chapter 8: Down the rabbit hole

SUSAN ORLEAN: I would wake up in the morning and think, “Okay, who do I call? Who should I talk to? How am I going to advance this reporting?”

I found myself pursuing really elaborate, amazing side stories: Orchid growers, the Seminole Tribe, the swamp, and the orchid collectors around the world, smuggling of rare species.

For instance, the Fakahatchee Strand, which was this natural paradise filled with ghost orchids actually was not at all a natural paradise. It had been stripped and was to be made into a huge subdivision. And it was one of the biggest land scams in the history of Florida. When this land development with streets and sidewalks collapsed, the land was abandoned and slowly but surely, nature crept back in, and it turned wild again.

Chief Billie was, at the time, the head of the Seminole Tribe. He shot a Florida panther, which set off this extensive legal challenge that ended up in the Supreme Court that raised the question of whether endangered species law should apply to Native Americans. And Chief Billie won and, as a result, was something of a hero among his people.

Lee Moore was an adventurer, a real oddball, a guy who believed in smuggling. He very proudly told me about smuggling art and artifacts, and almost anything he could get his hands on, including, for a while, orchids. I mean, certainly what he did was largely illegal, but he had a purity that I found touching. He was an amazing storyteller and probably a huge liar.

A photo of an adult male Florida panther in Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park, 2006. Photo: David Shindle for the Conservancy of Southwest Florida, via the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Learn more about the Florida panther.

Chapter 9: Index cards spread across the floor

How do you manage an unmanageable project? Get a birds-eye view, and don’t be afraid to spread out.

SUSAN ORLEAN: Not to overstate this, but my career was at stake. I had taken a long leave of absence from the New Yorker to work on the book. I reported for two years and wrote for a year. So there was a real feeling that I had paused my magazine writing career to do this. So I really felt that everything was on the line.

I knew what I wanted the book to feel like when it was written. But I realized that the challenge of keeping a reader engaged for 300 pages was a whole leap creatively, and certainly a leap structurally. How do you structure, particularly, a story that I didn’t feel would work merely as a chronological telling?

I transfer my notes onto 5×8 index cards. Sometimes it will be a fairly long quote. Sometimes it will be a reference to a document. Sometimes it’ll simply be a fact that really stuck out that I absolutely want to include.

For instance, I had learned this amazing fact, which was there are a lot of armadillos in Florida, and I thought, oh, well, that’s interesting that they’re native to Florida. Well, they’re not native to Florida. Armadillos carry leprosy. It’s just part of their DNA. So this lab in Jacksonville had all of these armadillos that were being used to study leprosy, and there was a breach, and they all got out, and they multiplied and became endemic to Florida. But they’re not natural at all. They’re not native to Florida.

And the idea that they came from a lab studying leprosy, it was to me one of the most bizarre, wonderful illustrations of the nature of Florida. So I had an index card that said, “Armadillo lab, Jacksonville,” to remind myself that I wanted to slot that anecdote in.

And I have these index cards spread out across a large room on the floor, and I move them around until I begin seeing thematic coherence and begin to figure out how I’m going to structure the book.

“Actual index cards I’m using working on my memoir,” writes Susan in the Medium post “Another Essential Writing Tool You Should Own in Large Quantities.”

Chapter 10: Back into the swamp

SUSAN ORLEAN: I convinced myself when I started working on the story that, of course, it was essential, in order to write this, that I see a ghost orchid. I went into the swamp repeatedly. And as time was rolling on, I was panicking and thinking, “How can I write this book without seeing this ghost orchid?” This is what it’s all about, pursuing and finding this rare thing.

We had set a date for our last trip in there where we were going to go see a ghost orchid. He had promised me. My book was due. I had spent so much time in Florida, and I thought, “This is it. I can’t … this is my last chance.”

I was in the swamp that day with Laroche, and it was a miserable day, hot, humid with a really heavy sky. He was the most maddening person I’ve ever written about. I mean, there were so many times when I just wanted to strangle him. He had promised me he was bringing all of the supplies we needed to be comfortable, like water and snacks, and all he brought were cigarettes.

We began this hike. We’re wading through the swamp, waist deep in this black water with God-knows-what swirling around us. Alligators, snakes, bugs, plants, and trees just sort of clinging to us and sticking in our hair and mosquitoes in a cloud around our heads. I was hot. I was dirty. I was covered with mosquito bites. I was wet up to my chest. My shoes were soaked with mud. I was really reaching the limit.

We were deep in the middle of the swamp. It was getting late, and we were lost. He was making a makeshift sundial to help us figure out which direction we were pointed in. I was so angry because I thought we were going to have to spend the night in the swamp. I was standing several feet behind him, just glaring at him. And it was increasingly clear to me that we were not going to find this ghost orchid.

I was heartsick. After spending two and a half years, how can I even do this book? I’ve never seen the ghost orchid. There was a moment where I was looking at Laroche, and I thought, “What kind of fool would go hiking through a swamp for a flower? You can get a flower, you can get beautiful orchids easily. You can go to the store and buy them. What kind of fool undertakes this really unpleasant journey just to get this orchid?”

And I looked around and I realized that there was only one other person in the swamp, and it was me.

Chapter 11: The deep end

How do you decide when to take the chance on a project? Sometimes you just have to dive in.

SUSAN ORLEAN: That the book was treated as a serious work of narrative nonfiction meant a huge amount to me. I felt validated. But I was done with the book. I felt like I had sent it out into the world, and it was now its own individual thing, and I wasn’t clinging to it in any particular way.

I started getting phone calls asking about the movie rights. I was flabbergasted. I certainly never imagined it having a cinematic version. I didn’t even think about it.

I was told they had hired a screenwriter, Charlie Kaufman, and I didn’t recognize his name, but my agent was excited. And then after a while, it seemed like it was taking so long. The producer, Ed Saxon, finally called me one day and said they had the script. “Do you want to have lunch?”

I like having lunch, but I thought, well, you could just send it to me. We met at a restaurant in Midtown Manhattan. And I just wanted to get a sandwich and get the script and be done. And he said, “Have a glass of wine.” And I thought, well, I don’t drink at lunch. He said, “Oh, come on. We’re celebrating.” So I had a glass of wine. We had our appetizers, we had our sandwiches. Then he said, “Do you want dessert?” And I thought, actually, I don’t really want dessert. I want to get the script, and I want to go back to the office.

Finally, he conceded and handed me a manila envelope, and said, “I just want to warn you, there are people in it who aren’t in your book.” And I said, “Well, that’s all right. I don’t mind.” And he said, “Just read it with an open mind and call me as soon as you’ve read it.” And we gave each other a hug goodbye. I headed back to the New Yorker, went into my office, shut the door, and pulled this script out of the manila envelope.

The first thing I saw was that it wasn’t called The Orchid Thief, it was called Adaptation. I thought, well, I’d rather have it called The Orchid Thief. I also noticed it was written by two people. It said “Charlie and Donald Kaufman.” And I thought it was just one screenwriter. And I began flipping through it, and I thought, this is insane. First of all, why am I in this script? I was so puzzled. So I closed the script and thought, this is just too weird. I’ll read it another time.

The next day, I flipped it open again. There was a scene where I’m nude with John Laroche, we’re obviously lovers. And I thought, this is nuts, and I closed it.

The third day, they finally called me and said, “What do you think?” I said, “Well, you can’t have me in this movie.” And the producer, Ed Saxon, said, “Oh, well, let’s talk about it.” And I said, “Well, look, Ed, no matter what, you cannot use my name. It’ll ruin my career.”

He said, “Well, Susan, everyone in the script is a real person, and they’re all using their real names.” And I said, “Well, that’s fine, but I can’t do this. People are going to think I actually had a relationship with John Laroche.” I don’t know what you people are doing with this crazy script, but I can’t be bothered with your hijinks. I just need to get back to work.

The producer and the director and Charlie Kaufman were all in a panic because they thought I was going to put the kibosh on the whole thing. I talked to a million friends, all of whom said, “Don’t do it.”

One day I woke up and thought, “Well, why not? Why not? This is an experience that isn’t going to happen to a lot of people. And why not?” It was a little like that feeling when you’re standing on the edge of a pool that you know is probably really cold. And you hesitate, and you hesitate, and then something clicks, and you jump in.

Chapter 12: Meryl Streep appeared on the screen

What happens when your work takes on a life of its own? You sit back and watch.

SUSAN ORLEAN: This was several months before it came out. My husband came with me. We went to a screening room in Midtown Manhattan. On the way down, I started feeling really queasy and nervous. And I thought, “Is it too late for me to say no? Can I tell them I can’t let them release the film?” And my husband said to me, “I’m afraid it’s too late. I think it is too late.”

It was me and my husband and Spike Jonze, the director, and the French distributor. And that was it. It was just the four of us. Oh, and Spike’s mother, I think Spike Jonze’s mother was there too.

When the movie ended, I sat there, and I was in shock. I think I blanked out the minute Meryl Streep appeared on the screen and said, “I’m Susan Orlean.” And from that point on, it was like the neurons weren’t firing. I could no longer process what I was seeing. I was experiencing it more like falling asleep and having a very strange dream. And Spike said, “What do you think of the movie?” And I thought, “I don’t know. I would have to see it again.”

I’ve seen the movie now probably 18 times, and the reason for that is when I was doing my book tour for The Orchid Thief, a lot of venues would show the movie in addition to me giving my talk. I would always think, “Well, I’ll just watch the first few minutes. I don’t need to see the whole movie.” Inevitably, I would end up staying and watching the whole thing. So it became this almost irresistible pull to watch it again and again and again.

I think I really appreciated it after I had seen it maybe three times. It took me a while to become desensitized to the shock of seeing myself portrayed and seeing words that I had written on screen, feeling like, “No, no, I wrote that. I’m Susan Orlean. That’s not Susan Orlean.” That’s when I began to really be able to watch it as a moviegoer and to appreciate that it addressed themes in the book so much more thoroughly and intelligently than a typical adaptation might have.

I wrote the book at, in some ways, a very difficult time in my life. I was in a marriage that was strained and struggling. I thought that I had suppressed all feeling about that as I was writing the book. I certainly never wrote about it in the book, but it was a time when I was lonely and concerned about what was going on in my marriage. Charlie put that all on the screen, and it shocked me. It shocked me so much that I’ve always wanted to say to him, “How did you see that? How did that aspect of what was going on in my life become exposed?” Because I certainly did not deliberately intend to write about that, yet writing of course is always coming from an authentic place in your soul, and it always reflects what’s going on in your life whether you know it or not. And evidently it did.

One of many book talks tied to a screening of Adaptation, this one in Texas in 2008. Thanks to book talks and screenings, “I’ve seen the movie now probably 18 times … I would always think, ‘Well, I’ll just watch the first few minutes. I don’t need to see the whole movie.’ Inevitably, I would end up staying and watching the whole thing.”

Chapter 13: Abandon an obsession

SUSAN ORLEAN: There was only one other person in the swamp, and it was me. While Laroche was undertaking this miserable journey through the swamp to collect an orchid, I was undertaking the same exact journey to collect my story. I almost had to sit down and collect myself when it struck me that what seems so strange to me about Laroche and so alien and alienating, that capacity to move on after he had become so passionate about something — the nature of my work paralleled the crazy nature of his obsessions perfectly.

I do a story about orchids. I live and breathe and think about orchids and talk to people about orchids and travel to see orchids and hike through the swamp to see orchids. And then when I’m done, I’m done. I’ll never write about orchids again.

And then I’m writing about libraries, and I’m thinking about libraries and talking to librarians and being consumed with the subject of libraries. And then I’m done. And I’m done. I move on. I never write about the same thing again.

It was a jaw-dropper. That moment for me was the reveal that it was never about the thing itself, it was about the pursuit. It was about the passion for something. It was about the desire.

Searching for something is the achievement. It’s the search that gives you purpose and makes you feel like there’s direction in the chaos of life. And it’s not about finally achieving that singular thing. That achievement will never live up to all of the effort and heart and soul that you put toward it.

It was never about seeing the ghost orchid. It was about the pursuit of it.

A ghost orchid. Photo courtesy Big Cypress National Preserve.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Susan for sharing the story of her creative journey with us. And I want to thank each of you for listening. I hope you found things in it that you can bring into your own work.

Whether it’s the way Susan found her big idea by digging around in a seat pocket on a plane. Or the way she moved past her own “wobbly moment” by relying on that outside push.

It might be the way Susan got her bearings — by asking questions or laying out index cards. Or it might just be the way she taught herself to begin — not once, but over and over as the project grew in scale and complexity.