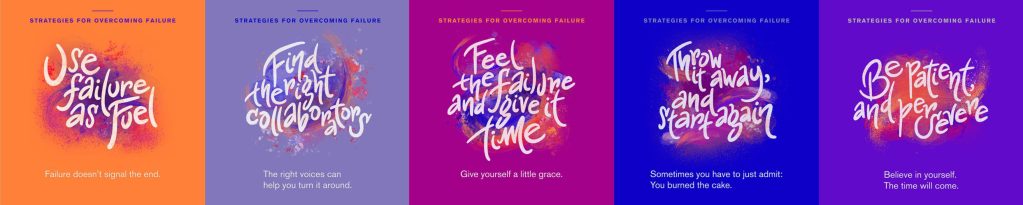

5 strategies for overcoming failure

Failure is a normal part — even an essential part — of any creative journey. But that probably isn’t what you want to hear after experiencing failure yourself. It’s easy to just want to crawl into a hole for a while. Today on Spark & Fire, we’re going to crawl out of that hole long enough to hear from 5 iconic creatives who have learned how to overcome failure to create something truly great.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

5 strategies for overcoming failure

ANN PATCHETT: I’m reading my own novel that I wrote, and I was 10 pages away from the end, and I can’t finish it. It is a disaster.

BEN FOLDS: It seemed like the album had failed.

RANDALL PARK: I remember just dropping the phone, collapsing into that couch, and crying. Feeling like I just got hit by a truck,

CHRIS McLEOD: Those are a few of the iconic creatives on today’s episode, talking about moments of failure on a creative journey. You’re going to hear from 5 different creatives in 5 different fields offering 5 different strategies for overcoming failure.

Failure is normal. The stories in our episodes have failures at every turn. You might even say, failure is an essential part of any creative journey. Which probably isn’t what you want to hear.

Nobody falls flat on their face, and smiles because they know they’re one step closer to success. Or maybe you are that zen about it. But for the rest of us, after yet another failure, all we want to do is just crawl into a hole for a while.

But — today on Spark & Fire, we’re going to crawl out of that hole long enough to hear from iconic creatives who have learned how to overcome failure to create something truly great.

I’m Chris McLeod, the Executive Producer of Spark and Fire. I spend most of my time inside our guests’ stories, shaping them into the episodes you hear on this show. Spending time with these creative journeys, I absorb a lot of wisdom that I get to carry into my own creative practice.

Here are 5 strategies for overcoming failure.

Our first strategy is about viewing past failure as inspiration. It comes from our episode with actor and writer Randall Park. Before he co-wrote the beloved romcom Always Be My Maybe, Randall was a struggling actor who went through some tough rejection.

Strategy 1: Use failure as fuel

Randall Park found his passion for acting and writing in college (here he is with the cast of “The Achievers,” put on by LCC). But turning his college success into a grown-up acting career … was not an easy road. Photo courtesy Randall Park.

RANDALL PARK: I was broke, living with my parents. I was in dire need of a job for financial reasons, but also just for my spirit.

This audition had come to me, and it was for a series starring Ted Danson. It was a sitcom called Help Me Help You, and it was for a one-day guest star role. I go to the audition, I’m sitting in the waiting room, usually super-nervous before any audition, but I had worked so hard on this audition. It really played to my comedic strengths. It was non-stereotypical, which was really refreshing, and it was so perfect for me that I actually felt okay. I felt like, “This is going to go good.”

I get called into the audition. I remember doing the scene and feeling so locked in, but also feeling so free that I was able to improvise, and the actor that I was reading with was able to play along. While it’s happening, I’m feeling so exhilarated and alive, and I’m feeling like, “Oh gosh, this is what a great audition is. I’m acting. I’m not auditioning, I’m acting.” I come out of that audition, and I go home just feeling like I got that job.

With acting, when you don’t have the part, they don’t call you to tell you you don’t have the part. They only call you to tell you when you do have the part. The day passes, I don’t hear anything from my agent. Tomorrow comes, I don’t hear anything. Friday comes, I’m getting antsy at this point. I call my agent. He says, “Okay, you’re still in the running. In fact, it’s down to you and one other actor.” And I was like, “Oh, who’s the other actor?” And it turns out that this actor is my friend Eddie Shin. Eddie is a fantastic actor, way better than me. I was like, “Oh no. Well, you know what? I think it’s okay because what I did in that room, no one else can do. I did me.”

So the weekend passes. Monday comes, Tuesday comes, Wednesday comes, I hear nothing. At the very end of the day I was like, “I got to call my agent.” And he says, “Yeah, you didn’t get it,” and I remember feeling like I just got hit by a truck, just dropping the phone, collapsing into that couch, and crying. Just breaking down. And out of everything I’ve experienced throughout my entire career, that was the darkest moment, and it was really just for a six-line role for one day, for a show that immediately got canceled, that most people don’t even remember. But for me, it meant so much more than that. It was going to be my sign that I was doing the right thing.

When you have experiences like that, you have to feel like crap. That’s just you being human. You can either use it as fuel, or you can let it bog you down and, eventually, take you out of the game. I actually quit shortly thereafter. I always drew a lot as a kid, and so I was like, “I think I’m going to try to become an architect.” I remember going to Santa Monica College and having to take basic physics in order to even apply to architecture school, and I remember just being completely lost. I couldn’t get any answers right, and quitting after the second day of that class, thinking like, “Gosh, I have nothing else to offer the world at this point, other than acting,” and quietly stepping back on the battlefield with my head down: “All right, time to go to war.”

CHRIS McLEOD: Something I can really relate to about Randall’s story is how, at first, he gives up. But pretty quickly he realizes that this failure doesn’t have to be the end. Even though there is nothing he can do to fulfill this particular dream, he can use the experience to fuel him to a career of his dreams.

Our next strategy is for the moments when you’ve been pouring your heart and soul into a project, then you zoom out for a moment, examine what you’ve made, and realize, for yourself — that you’ve failed.

It comes from best-selling author Ann Patchett. When she was working on her novel The Dutch House, she had been at it for ages and finally finished. Or she thought she did.

Strategy 2: Throw it away, and start again

Reading her latest manuscript, writer (and bookseller Ann Patchett faced a hard choice when she realized: There’s a mistake on page 36.

ANN PATCHETT: I had been having a hard time finishing the novel. A lot of demands, a lot of busy-ness. I was rushing thinking, I can get this done, I can get this next thing done. I finished the novel, and I’m feeling really good about things. And I’m doing my read-through of the book. I was upstairs, laid out flat on the floor of my office with my little green meditation pouf under my head, and it’s great, and it’s great, and it just goes down and down and down as I’m reading it. I’m reading my own novel that I wrote, and I was 10 pages away from the end, and I can’t finish it. It is a disaster. And I’m thinking, oh my God, I made a mistake on page 36, and the whole book is on the wrong path. I just sort of laid there and looked at the ceiling. I knew it was wrecked. I didn’t know how to fix it. And I deleted it.

I went downstairs and I told Patrick. And he said, “Shouldn’t somebody read it? Shouldn’t I have read it?” I said, “Well, one, it’s gone.” I said, “My only joy at this moment is knowing that you didn’t read it.” Like, I really want you to love me. I want you to hold on to that memory of me as a really competent novelist.

People would say to me, “It must be like losing a child.” And I said, “Jesus Christ. It’s like burning a cake.” It’s not like losing a child. You made a cake. It was hard, it was complicated, you left it in the oven too long. It’s burnt. You can slice it in half and eat some of the little fluffy parts out with your fingers over the sink, but you can’t save a burnt cake. You know how to make the cake. Your ingredients are all still out there. You just throw it away, and you make another cake.

CHRIS McLEOD: Every time I hear this story, all I think about is the little fluffy parts of the cake that might not be burned too badly. It’s the part of me that doesn’t want to accept it when I’ve completely failed. But I don’t think the fluffy parts are the point. Sometimes you have to just admit: You burned the cake.

Our third strategy is about surrounding yourself with collaborators who understand why you failed, and can help you turn it around. It comes from the songwriting duo Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez, who wrote the iconic music for Disney’s Frozen, a project that — for more than half a century — had been stuck in a state of failure.

Strategy 3: Find collaborators who make your head turn

Kristen describes how the sisters’ characters developed at a story workshop: “Anna’s the screw-up, a wild child but also a character who’s always trying and has a giant heart. And then we discovered Elsa. Okay, Elsa’s going to be the perfect one.” Image courtesy of Walt Disney Pictures

KRISTEN ANDERSON-LOPEZ: Disney himself had tried to do a version of the Snow Queen way back in the ’50s, but the Snow Queen was just too abstract, and now this amazing director, Chris Buck, who had done Tarzan, had worked with another writer, and they had found their way to a sister story. The Snow Queen, like Elsa’s character, was this evil, villainous woman with spiky blue hair, and Anna was this perfect princess in a really annoying way. We actually sat in a room where Idina and Kristen were brought in to read this version of it, right at the very beginning of our process.

And they also rolled in a Yamaha keyboard, and somebody started to play “You Are the Wind Beneath My Wings” right at the very end, which Idina and Kristen sang in harmony across John Lasseter, and Bobby and I both didn’t know that that was going to happen, and we were a little bit like, “Oh Jesus, are we going to have to write ‘You Are the Wind Beneath My Wings’?”

We wrote a couple songs for that version. We wrote a song called (singing) “I Want You to Be Cool with Me” for evil Elsa. We had written a huge opening number watching the two sisters grow up that was an epicly long seven-minute opening number for the first screening.

ROBERT LOPEZ: We wanted people to cry at that opening, because we felt like we had written something very emotional, but everyone’s eyes glazed over. It was just a dead, limp audience for that first song, and I kind of felt like, well, this whole experiment and being emotional in my music is going terribly. I should be doing comedy. Let’s get out of this project.

ANDERSON-LOPEZ: That screening was on my 40th birthday.

ROBERT LOPEZ: For some reason, they had this puppet of Olaf, and one of the animators thought he could do puppetry. And the lip-sync was all off the way he did it, and I was always like, “Oh God.” And they had him come in with a big cake and Olaf the puppet to sing “Happy 40th Birthday” to Kristen in the middle of this terrible note session.

KRISTEN ANDERSON-LOPEZ: It couldn’t have been more awkward. We were told no matter how well it goes, we’ll at least go to Dairy Queen because that’s what we always do. We always go to Dairy Queen after a big milestone, and it went so horribly that the director, Chris Buck was like, “We’re not going to Dairy Queen.”

The writer at the time was like, “I don’t think this is a musical. I think …” He had written a really cool live-action script. He had written a good story with good characters and good dialogue, but nothing about it sang. It was all about two unlikable people doing very nuanced things, and nothing about their hearts or their emotions felt big.

ROBERT LOPEZ: The director Chris Buck said, “Would Fräulein Maria sing ‘The Sound of Music’ after she had just sort of stabbed her sister in the back? I’m not sure.”

I said, “We could easily make this not a musical, and we could just shake hands and step away, because I’m not sure that we have the ingredients for a musical here with the characters the way they are.” And Lasseter said, “Oh no, this is going to be a musical, and you’re staying right where you are. We’re going to make it one, and it’s going to be a good one.”

KRISTEN ANDERSON-LOPEZ: In a different circumstance, that could have been a very depressing day, but for me it was the beginning of something so exciting. I was so energized by: I know what this can be. I know we can make this incredibly great. If I can just find the right way to be heard about the different changes we could do to really make it a musical and an important musical for sisters.

There was this amazing voice behind us in the chairs, bringing out these really good notes, who happened to be Jennifer Lee. She was there working on Wreck-It Ralph. What she was saying was so good, every time she spoke, I would sort of turn and go: “Yes, yes.” And within a month she was the writer. And that was the best, best turn of luck.

CHRIS McLEOD: You can really hear how they went through all the stages of grief in one day. Acceptance was probably when they decided not to go to Dairy Queen. But how inspiring is it to hear how quickly they were able to move through the failure? They figured out that, with the right collaborators, it could be something special.

But sometimes it’s not possible to turn it around in a day. It could even take decades.

For our next strategy, we’ll hear from the producers of the hit series Queen’s Gambit, Allan Scott and William Horberg. When they were trying to adapt the story from book to screen, there was 30 years of failure after failure before it finally paid off.

Strategy 4: Be patient, and persevere

The long road to this shoot for The Queen’s Gambit in 2020 (featuring Thomas Brodie-Sangster as Benny and Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon) begins in another century. Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix © 2020

ALLAN SCOTT: Four or five different directors wanted to make the movie. I did this over a period of many, many years. And, you know, these processes take forever. You sit down with a new director, or one you haven’t met, but you do those things because you think they’ve got a shot. There wasn’t a studio in the world that wanted to do a chess movie: “We love your work. We love the script. Bring us something else.”

Bertolucci was the first director I worked with. And we used to go to an Italian restaurant for lunch every week. And I would sit down with him and say, “Now, Bernardo, let’s talk about what we need to do.” He said, “It’s all right. You wrote the script. You have the script.” I said, “Yes. And you liked it, I think.” He said, “I loved it.” I said, “Yeah, but what do you want to change?” “Nothing. Nothing. We just shoot.” And we couldn’t get it together.

And then proceeded to work with the wonderful Danish director Thomas Vinterberg. He was, at that time, the hottest young director in the world. At the end of our long weekend together, I said, “Okay. How do I get you to commit?” He said, “What I do, this is my process: I rent a house in the countryside in Denmark with you, me, two of my line producers, the art director, the composer. And we all share the house for about two months. And we talk about the project every day.”

I said, “Thomas, I’m too old to do that. I’m not going to spend two months in a house in the middle of the Danish countryside with six people I don’t know.” So I guess I turned him down. I thought he turned me down.

But then, many years later, I finally found a director who was acceptable to all the studios. And he happened to be a director who’d never directed a movie in his entire life, and it was Heath Ledger. And Heath was just great. He called me out of the blue. I didn’t know him. I went to New York to his house to look at his movie shorts and documentaries and commercials and music videos.

You could see in 10 minutes that the guy knew how to do this. And he was absolutely rock-solid on the story. He was just a very wonderful human being. He was in New York, and I was in London. And one day I spoke to him, we were talking about the music, he knew nothing about the music of the period. And I’m glad to say that was my high point in music. I’d given him a whole raft of things I thought were suitable. At 7, 8 o’clock, we hung up, and the following morning I learned he died three hours later. And it was such a shock to me. I was so fond of him by then that I just sort of lost heart in the project.

BILL HORBERG: I reached out to Allan and told him of my love of the book. It seemed like it was probably at a moment between these many directors, and I said, “Could I throw in with you?” He very graciously offered to work together to see if we could find a solution to getting this made.

Again, a number of terrific directors read the material, came and met with us. For me, it was probably about 10 years. Allen had already been at it for 20. There was never a year where it wasn’t almost about to get made. I assumed I was going to be making this movie. It just found a reason to not happen, often at the last minute. At some point you beat your head against the wall, and you go, “Man, maybe this is just not meant to be.”

I don’t believe that there’s a kind of rational marketplace. If I’m getting rejections, it’s not like I think the person who’s rejecting this has the truth. I just think I haven’t found the right person at the right time and the right elements and the right combination to make it happen.

You have to start not with the like, you have to fall in love. It doesn’t happen that often. But when you do and you get knocked over by something, you know that feeling, and you don’t want to give it up.

Just to get anything made is such an epic uphill struggle that stick-to-it-iveness is an essential thing for anybody who’s going to pursue a creative path. If you were to turn away at any of the points offered to you to get off the path, you will. But then when you get so close and you’ve also invested so much of yourself in that process, it’s very hard to let go of that and walk away.

The only way to do it is if you can’t not do it, because if you can not do it, eventually you will not do it. But if it’s like breathing or sex, and you just have to do it, as part of living, you need that element of perseverance. When you find a good story, you are going to get this thing made or die trying.

CHRIS McLEOD: My favorite moment in this story is when Allan decided to turn down a director himself because he didn’t want to spend two months in the Danish countryside. He was even willing to admit failure if the opportunity wasn’t right for him. He knew he could keep persevering until every piece was in place.

Our final strategy is for the times when we assign failure to ourselves, because we think our work wasn’t good enough.

It comes from singer/songwriter Ben Folds. After his band, Ben Folds Five, released their 1997 breakout album Whatever and Ever, Amen, Ben was his own worst critic.

Strategy 5: Feel the failure, and give it time

Ben Folds wanted to create a great, crunching, emotional, honest rock record on a Steinway piano. With the Ben Folds Five’s second album, he got that chance.

BEN FOLDS: It was a disappointment. The album wasn’t as good as I thought it should have been. It didn’t sound as good as I had wanted it to. I was really aware of the times where I choked the life out of it. It wasn’t nearly as successful as it should have been. All the metrics of the music business constantly put you just a few inches behind the carrot. It just keeps dragging along.

It’s like, “Wow, you guys have had the first radio success with a ballad on modern rock.” Really, we have? “Yeah, except this week, there’s one that looks like it’s going to probably overtake you.” Oh really? What’s that? “It’s this band, they’ve got a song called ‘Bittersweet Symphony.’ It seems to be doing pretty well. It’s in a Nike commercial.” Really? Is it beating us? Next week, no one had heard of us anymore. Everyone had heard of that.

So it seemed like the album had failed. So emotionally, I found it a complete rollercoaster. Yeah, I was rocking and rolling. There were a few years I had a hard time.

No one wants to hear the woes of someone who’s gotten what they asked for and what they want when everyone else would like, which is some success in something. But your mind is not set up for it. If you’re a thoughtful person, I think, it especially makes it tough.

So I was definitely a glass-has-not-got-any-water-in-it-at-all guy.

When I look back on it now, I’m like, “It’s a good record. It sounds good.”

CHRIS McLEOD: Anyone with high expectations on their work can relate to this one. How funny to look back at another era and think about what you thought you wanted. I’d guess Ben doesn’t lose much sleep about not getting a Nike commercial 25 years ago. I love how Ben has been able to shift his perspective over the years. It shows that sometimes, to overcome the feeling of failure, you just need to give it a little time.

We hope you enjoyed this episode of Spark & Fire. Maybe what you take with you is how Randall Park used his failure as fuel.

Ann Patchett shared her brilliant metaphor to help us throw it out, and start over, as if you burnt a cake.

Maybe the strategy that you take away is to find the collaborators who will make the project even better, like Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez.

From Allan Scott and William Horberg, we learned to be patient and persevere. Or, like Ben Folds, sometimes to overcome failure, you just need to change your perspective, and give it some time.

Whatever you took away from this episode, we hope that the next time you experience a moment of failure in your own creative practice, it will bring you some insight to help you overcome it.

About the Creators and Host