Find the people who see your dream

In the 1990s, Aasif Mandvi was a struggling actor looking for roles that didn’t seem to exist. So he wrote Sakina’s Restaurant — a solo show about an Indian immigrant family who owns a restaurant in New York City. When Sakina’s Restaurant premiered off-Broadway in 1998, there was really nothing like it. In this episode, Aasif tells the story of writing and starring in this pioneering one-person play. Perhaps more than any other medium, a one-person show appears to be the work of only one person. But Aasif’s story shows it takes a number of people — who share your dream — to bring it to life. In order to break new ground, you need to find allies who see your dream.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Your dream is their dream

- Chapter 2: My first performance

- Chapter 3: I can do that

- Chapter 4: Writing the characters

- Chapter 5: The big-time acting teacher

- Chapter 6: The audition — and everything after

- Chapter 7: A chance encounter

- Chapter 8: Performing Sakina’s Restaurant

- Chapter 9: Finding the money

- Chapter 10: A tempting offer

- Chapter 11: 20 years later

- Chapter 12: What Sakina’s Restaurant means to me now

Transcript:

Find the people who see your dream

Aasif Mandvi, playing one of six characters, in the revival of Sakina’s Restaurant in 2018. Photo Lisa Berg

Chapter 1: Your dream is their dream

AASIF MANDVI: You’ve got this thing, let’s say it’s a pen. It’s a perfectly good pen. And you’re like, “Hey, invest in my pen.” Now, not everybody needs a pen. They don’t use pens and that’s okay and that’s just what it is. But eventually, you’re going to find that person who’s like, “Oh yeah, I love pens.” That’s the person that you will ultimately collaborate with.

The people who were my allies were the people who understood theater. They were like, oh we know what theater is. We know how these stories can be transformative and important to the cultural tapestry of this country and of the world. It’s really about finding the person that sees your dream in the way that you see it. Your dream is their dream.

JUNE COHEN: That’s Aasif Mandvi. And he’s about to tell us the story of writing and starring in the one-person play Sakina’s Restaurant.

It’s the specific story of Aasif’s Off-Broadway play — which was trailblazing for its spotlight on an immigrant Indian family. But the takeaway is universal: To break new ground, first find the allies who share your dream.

As Aasif takes us through the challenges and triumphs of bringing Sakina’s Restaurant to life, you’ll hear how to embrace the allies right in front of you — even if they’re not who you’d expect. And you’ll learn the right collaborators can understand your dream with a clarity you don’t even have yourself.

And here’s what you need to know about Aasif and Sakina’s Restaurant. Aasif was born in Mumbai, and lived in the UK until he was 16. His father owned a corner shop. You may know Aasif from his decade-long stint as a comedic correspondent on The Daily Show. Or for his lead role in the Broadway production of Disgraced, a Pulitzer Prize-winning play. There are also his supporting roles in TV shows like ER and The Sopranos.

But back in the late 1990s, Aasif was a struggling actor looking for roles that didn’t seem to exist. So he wrote Sakina’s Restaurant, a one-person show about an Indian immigrant family who owns a restaurant in New York City. Aasif performs monologues as all six characters in the play, who were inspired by people in his own life.

When Sakina’s Restaurant premiered off-Broadway in 1998, there was really nothing like it. It ran for 7 months and won an Obie Award that year. Twenty years later, in 2018, the play returned to the stage. And in 2019, it was released as an Audible Original audiobook.

I’m your host June Cohen, and on this episode, you’ll hear original music composed for piano and metallophones. For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com.

[THEME MUSIC]

Chapter 2: My first performance

AASIF MANDVI: It was the first time that I performed. I was in England in kindergarten. It was about these three brownies. In English folklore, brownies are sort of like pixies or impish creatures that do chores and stuff. They’re little brown people that do chores for white English people. And they’re called brownies.

Meet the Brownies, characters made popular by artist Palmer Cox in the 1800s, and then indelibly portrayed by a young Aasif Mandvi In his first performance.

The other kids had just regular brown tights. My mom didn’t have tights, so we went and got tights and I put them on and they were completely see-through. So I got black tights and put them underneath the brown tights. I remember just being, “Oh, this is weird. I look different.”

They had taken all the desks out in one of the classrooms and they’d built a little stage. It was like folding chairs. And at that age, other kids would just come on and forget their lines and pee their pants instead. I was clearly very invested and I was very present in the moment and I knew all my lines. Everyone came up to my mom afterwards and was like, “Oh, he was really good.” It was clear to my mother and everybody in the audience that performing was something that I took to like a fish to water.

We were immigrants to this. There was no idea that you could make a career out of being an actor. My mother’s fear was that if this is the thing he’s good at, and he’s clearly not good at science and math, then we have a long road.

More Brownies, drawn by Palmer Cox.

Chapter 3: I can do that

How do you break the cycle when you can’t find a way to create? Find someone else with a dream like yours.

AASIF MANDVI: There wasn’t any work. There weren’t a lot of brown actors in New York at the time, because there were no parts outside of maybe just doing Shakespeare in regional theater or something.

I started doing stand-up when I first got to New York. In my standup, I started doing a character with my father’s voice, imitating my dad and his accent. John Leguizamo was doing this one-man show called Mambo Mouth. And he was doing these characters which are more fleshed out with a story. I’ve never seen that before. There was never a story about brown people. It didn’t exist in the theater. It didn’t exist! I was like, I can do that. If I’m going to break this cycle of where I am, I want to write the kind of parts that I want to play.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice the sense of wonder in Aasif’s voice as he talks about John’s one-person play? He’d never seen anything like it before. And seeing John’s work — the work of someone with a dream kind of like his — was exactly what he needed to jumpstart his own dream.

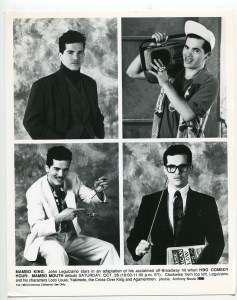

John Leguizamo’s work in Mambo Mouth showed Aasif Mandvi that a solo show could tell stories no one else was telling. Images HBO/Anthony Neste

Chapter 4: Writing the characters

AASIF MANDVI: It came from inside of me. These characters are all people that I knew, because they were all people that I had grown up with. I mean I used to think, “Oh, I’m writing this character that’s based on my dad or based on my mom,” and they are. But at the end of the day I think they really are all facets of myself.

I was that wide-eyed high school kid who showed up in Tampa, Florida, at 16 years old thinking: I’m in America, where else would you want to be? And then the realization of what that meant, and that America is not just an episode of Flipper.

I thought when I showed up in Florida, I was like, “Oh, my life will be great. I’ll be friends with a dolphin and Miss Teen USA will be my girlfriend.” That’s what I thought. It’ll just be like the movies. That’s Azgi. The 16-year-old Indian kid who came to America with that kind of wide-eyed innocence, that he shows up thinking it’s all going to work out. And then realizes, “Oh, I need to find something authentic in myself, and America can’t really give it to me.”

Farida, the character of the mom, is me dealing with a kind of disillusionment with what her life was supposed to be versus what it is. Sakina is me sitting on that fence between cultures. Samir, the little kid, is me when I was a little boy going back to India and having to give his toys away. They’re all expressions of me.

Chapter 5: The big-time acting teacher

AASIF MANDVI: I was working for a woman. She baked pies and cookies and cakes, and then sold them at intermission at Off-Broadway theaters. And so she sent me to the American Place Theatre. And Wynn Handman walks by and then she said, “He’s a big-time acting teacher.”

Leguizamo had been in his class when he developed Mambo Mouth. And I was like, “That’s what I want to do.” And then she said, “You have to be really good to get into his class. You have to be really professional. You probably won’t get in.” And I was like, “Uh-huh. Okay.” Then I found out that my girlfriend was auditioning for his class. And I said, “Well, I want to audition for his class.”

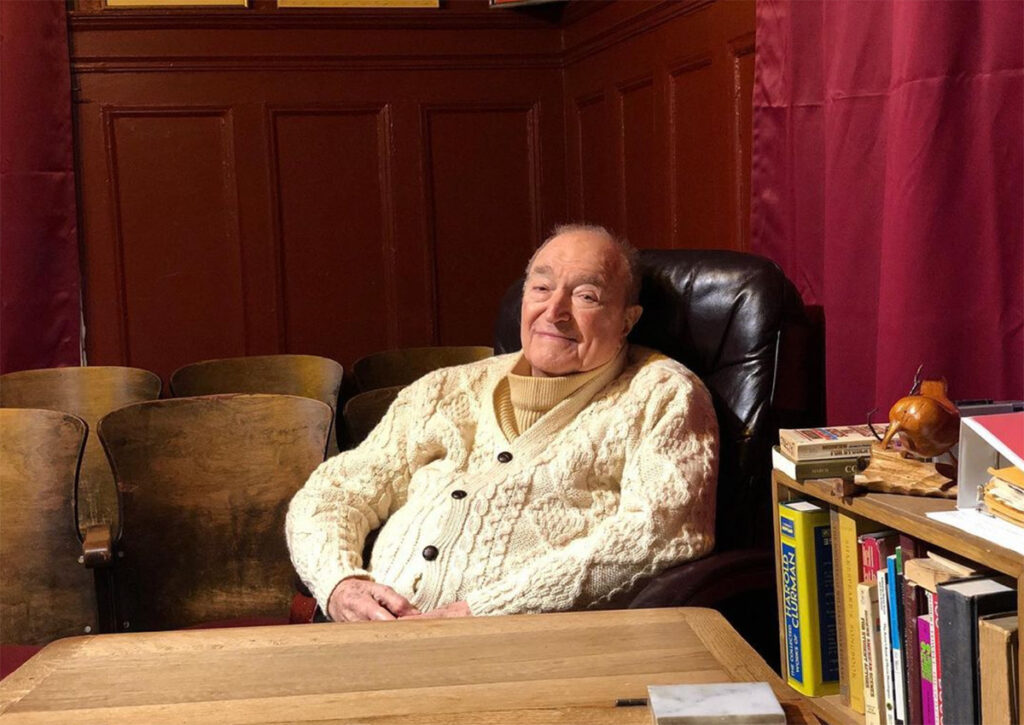

A portrait of acting teacher Wynn Handman, from the Instagram account for the Wynn Handman Studio. The quote accompanying this post is worth a click through.

Chapter 6: The audition — and everything after

How can you bring your dream to life? Get up from your computer, and find a human laboratory.

AASIF MANDVI: I went to the audition for Wynn Handman’s class and I took a monologue that I had written and performed it for him. I didn’t know if it was going to be any good. Like other people were doing Chekhov and Ibsen and Shakespeare and Shaw and stuff, and I was just working on Mandvi. And he let me into his class.

Twice a week, I would go bringing in these original pieces, and performing them, just get the feedback of the class. It’s much better than sitting at a computer or a typewriter. I had this really wonderful laboratory that I got to work in.

I took a monologue that I had written about this Indian man talking to his daughter. The father, Hakim, was the proprietor of the restaurant and the patriarch of the family. The daughter, Sakina, she’s a teenager. She’s been betrothed to an Indian boy. I was literally stealing stuff from what I had heard my dad say over the years, like “You think that you’re going to wear all this makeup and dress like an American girl.” Wynn said to me, “Where is he?” And I said, “Well, he’s probably in this restaurant that he works in.” And he said, “What if the phone keeps ringing, and he keeps getting interrupted?”

Now you had a man who was trying to have this conversation and, at the same time, being pulled in different directions.

I would do the monologue and then Wynn would go, “And the phone’s ringing. The phone’s ringing. Go get it, go get the phone,” because he’s got to talk to his customer. He doesn’t want to be rude to his customer. And I’d be like, “Oh my God. Hello. Hi, Sakina’s Restaurant. Good, good to see you.” And you have to make small talk and sort of be like, “Well, you know” and he’s laughing. His daughter’s leaving and he’s in the middle of trying to explain to her the things about life that he wants to tell her: “You think they’ll accept you. You think you’ll become one of them. You’ll always be a brown girl. This will always be your life. You’ll never be one of them.” She’s walking out of the room and he’s got to get her back. And then he’s clapping his hands or he’s covering the phone and saying, “Come back here.” And then he would go back, “Hi, yes, of course. Yes, table for three. Yes. Yes.”

And it just clicked.

The piece became alive. It had tension and it had stakes. Then I just started building on that.

n a scene from the 2018 revival, Aasif Mandvi works the phone in Sakina’s restaurant while silmultaneously parenting a rebellious daughter. Photo Lisa Berg

JUNE COHEN: When Aasif took Wynn’s suggestion — and included the ringing phone — did you marvel at the way everything just clicked? How it breathed new life into the play? This is the power of a trusted mentor who shares your dream — they open doors you can’t see.

Chapter 7: A chance encounter

AASIF MANDVI: I didn’t know anybody who could direct it. I was working as a cater-waiter and that was how I made money back then. All the other people wearing tuxedos and walking around with trays were just trying to get an agent. They were just trying to get a job.

Kim was a woman that I was cater-waitering with. She wanted to be a director; she directed a couple of things, I think, small things here and there. We were just talking and I said, “I’ve written these characters.” And she said, “I’m a theater director.” And I said, “Great, you want to direct my show?”

She was working in an office, that was her day job. And we’d go there and go in the conference room and we would just work on these characters. We were sitting there and we were kinda stuck and Kim said to me, “Have you written anything else? Have you just got anything else that you’ve been tooling around with?” And I said, “Well, I got these little parables or something. I don’t know what they are.”

I had read Khalil Gibran a while earlier and I think I just had it in my subconscious. I started writing these Khalil Gibran-ish-type poems, little stories. I was trying to write something that had a spirituality to it, or a kind of meditation to it. They were like little doodles, and they didn’t really mean anything. And I didn’t know what I was going to use them for. Just let my mind just wander on its own and just come up with stuff that didn’t feel related to the thing that I was working on.

And it wasn’t until Kim, my director, told me: “These things, they’re related.” That’s how the parables that Azgi tells ended up in the play. Those parables become Azgi processing who he is, weaving through the other stories. The play had more texture after that.

Chapter 8: Performing Sakina’s Restaurant

Why does a performance become better over time? Because the brain can take risks and invent things it could never invent before.

AASIF MANDVI: We did the first performance of it in a very rudimentary form at the West Bank Downstairs Theater on 42nd Street. It was very bare-bones. It was like a folding table and some props in the corner and a hat stand. That was the set.

I just thought it was just going to be random people just coming, and I would just get to do it anonymously. Nobody knew who I was. I didn’t know who they were. Kim came backstage and she was like, “Martha Plimpton’s in the audience.” And I just remember being like, “Oh my god.”

And then she came back and she said, “Wynn Handman’s in the audience.” And then I was like, “Oh shit, I’m really terrified now.” But then we got up and I did it and it was good. He came up to me and he said, “Good job.”

But that was about it. There was a kind of performative aspect of it. We just kept doing it around town. You don’t have the confidence to take risks initially, because you’re still just trying to navigate the show itself.

And then at some point, it became true. It’s one of the beauties of theater, as opposed to doing TV or movies. Your body just knows the choreography of it so well. The brain is no longer thinking, “Well, I have to say this now and I have to do here and I have to go there and I have to be this and I have to pick up the glass and I have to talk when I take a sip.” You’re not doing that anymore. That’s when you can suddenly take off. The brain can then take risks, then invent things that it could never invent before.

The New York Theatre Workshop was having a night of solo performances. Somebody dropped out. And they called me and they were like, “If you want to do a night where you do Sakina’s Restaurant, we’d be happy to give you the stage.” Wynn came again to see it. He came up to me afterwards and he said, “I think it’s ready now. I’ll give you the stage and I’ll give you the space. We should do it at the American Place Theatre.” Also, Wynn was like, “I’m a not-for-profit theater. We need to go get money to do the show.”

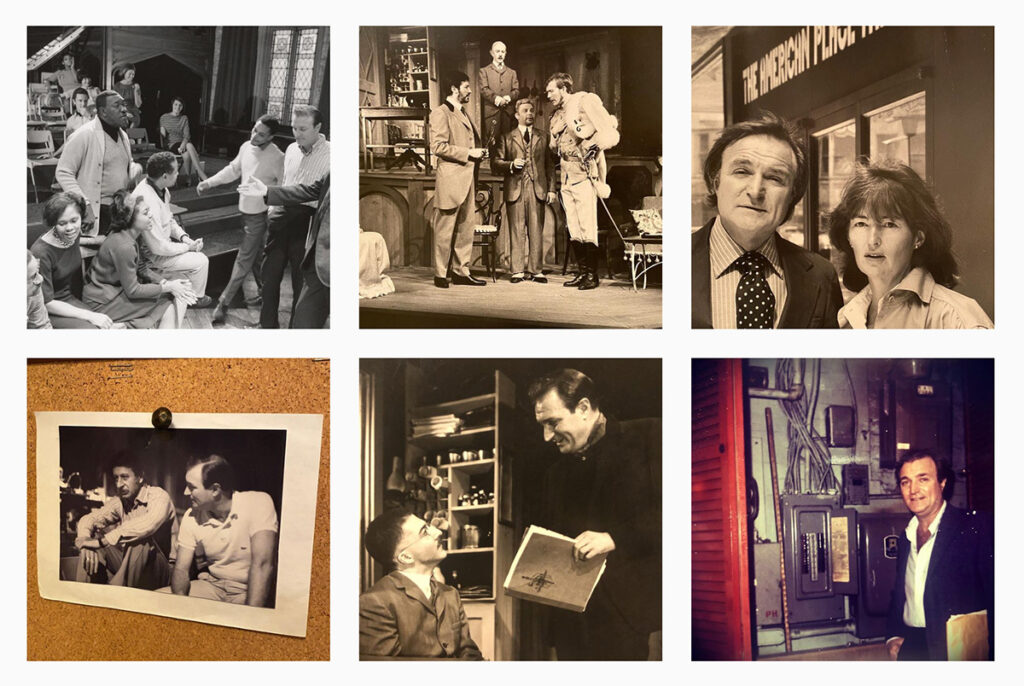

“We should do it at the American Place Theatre.” The site of many groundbreaking performances, this theater was legendary as a launch pad for talent. Collage from the American Place Theatre Insta.

Chapter 9: Finding the money

How do you find people to champion your dream? Embrace the allies right in front of you — even if they’re not who you’d expect.

AASIF MANDVI: We needed $50,000 or something to do the show. We thought, “Oh, well, we’ll go to the South Asian community. They will support this show, and they will give money to let us put it on.” Wynn and myself were out wining and dining rich Indian people to try to get them to give us money. We were like, “Well, could you just give us $5,000 here, $5,000 there?” We’d get a check for a hundred bucks. Be like, “Good luck to you, kid.”

People just didn’t understand what I was doing. They were like, “What do you mean you’re going to do a one-man show? It should be a Bollywood musical. It should be three hours and music and song and dance, and then it’s something. What is this? One person for an hour and a half? What are you going to do?”

These Indian people, as wealthy as they were and as cultured and educated as they were, they weren’t really going to theater because the theater was not for them. There was never a story about Indians, about the Indian immigrant experience, the South Asian immigrant experience. It didn’t exist.

Ironically, they were not my allies. The people who were my allies were the people who understood theater. They were the people that were going to Broadway shows. The theater spoke to them. It was part of their experience. So they gave us money because they were like: We know what theater is. We know how these stories can be transformative and important to the cultural tapestry of this country and of the world.

We cobbled together the money. There were some theater patrons of the American Place Theater and then some of Kim’s friends. And we did a run. The Times came to see it. And we got a love letter in the New York Times. Nobody had ever seen a show like this. That happened, and suddenly the ticket sales, boom, we were sold out. The play was only supposed to run for four weeks. Wynn said, “Well, we’re going to extend for six weeks.” Okay, and then we sold out and then we were going to extend for eight weeks. And we were still selling out.

“We got a love letter in the New York Times,” says Aasif. Reviewer Anita Gates called it “funny and endearing” and a “wonderful one-man show.”

JUNE COHEN: Did you hear the confusion in Aasif’s voice when he realized his expected allies weren’t rallying behind his dream? At least not yet … At this early stage, he needs a different kind of ally — people who already see what he sees.

Chapter 10: A tempting offer

AASIF MANDVI: I got offered a play by Terrence McNally called Corpus Christi, which was being done at the Manhattan Theatre Club. It was all about Jesus. It was about a gay Jesus. It was getting a lot of attention and protests. And I got offered to be one of the disciples in the play. My agents were telling me, you got to go do it because it’s going to be huge. It’s on the cover of Time Magazine. You got the great review in the New York Times, now just go capitalize on that and go do this other play.

And I remember I called Wynn Handman and I said, “Wynn, my agents really want me to go do this play. And they want me to leave and close Sakina’s Restaurant and go do Corpus Christi.” And Wynn said to me, he said, “Why on earth would you close your own show to go be in an ensemble with eight other guys?” And I was like, “Well, because they’re saying it’s going to get a lot of attention and da, da, da.” And Wynn said to me, he said, “I know that play. And I think Terrence McNally is a terrific writer, but that play’s going to close in two weeks.”

“I think you’d be making a huge mistake if you go do that. Here’s the deal I’ll make you. If you stay with Sakina’s Restaurant and don’t go do that play, I will keep you open till January of next year, even if I’m losing money.” So he was giving me five months to keep doing the play. It’s rare for a producer to say to you, “I will do this even if I lose money.” And so I didn’t go do Corpus Christi. Corpus Christi did close in two weeks, and we ran for six months.

I actually get emotional thinking about this. Wynn was dedicated to something that was bigger than just making money. I can only assume he did that because he believed in me and he believed that if we kept it open, it would eventually find the audience.

By the time we got to the fall, there were buses of South Asians coming in from New Jersey and Long Island and stuff, because they’d heard about this play and they were like, “Who is this kid doing this one-man show Off-Broadway in New York?”

When they saw it, it did speak to them. And then they got it and they were like, “Oh, this is what you’re doing.” Then it became, “Oh my God, you’ve got to see this play…”

JUNE COHEN: Can you imagine being in Aasif’s shoes, having to decide between this prestige project and the show he’d put his heart and soul into? Aasif’s agents want him to succeed. But they don’t necessarily share his dream. Wynn is the single voice giving Aasif the confidence to keep going — right when he needs it most.

Chapter 11: 20 years later

AASIF MANDVI: I often joke that in 1998, Sakina’s Restaurant was a comedy. In 2018, it was a tragedy.

The Audible people produced the live stage production in 2018, before it went on to become an audiobook. When the folks at Audible came to me, initially I was like, “It’s a dated piece now, it’s an America that we don’t even live in anymore.” They were like, “Let’s just keep it set in the time period that it was written,” which is like the mid to late ’90s. And so it had a kind of, almost like a period piece. It was like, oh right, I remember this, the Great Depression.

That whole story just had a kind of weight to it that it hadn’t had before. “Oh, this is who we used to be as a country. Azgi loves America. America is the land of opportunity and where he wants to be.” And suddenly here we were seeing the demonization of immigrants, the criminalization of people coming across the border. Because of that, the immigrant story was way more potent.

In 1998, I had the Orthodox Jews and Armenians and Greeks and all kinds of people come up to me and say “This is my family. Oh my God, I see my own parents.” But non-immigrants, quote unquote like WASPY white people would come up and be like, “It’s such an interesting window into this world I never thought about, or never knew about.”

In 2018, those same people were coming up to me and going, “I’m so sad that America is not this place anymore.”

“It surprised me that, in some ways, it felt more resonant today than when we did it 20 years ago,” says Aasif Mandvi in a short video for Audible’s revival of Sakina’s Restaurant. Click through to watch the video clip.

Chapter 12: What Sakina’s Restaurant means to me now

AASIF MANDVI: Sakina’s Restaurant. It’s a home for me. It feels like the way you feel about your family. It just is part of me. It was something that I needed to express.

So much of my career, especially as a brown actor in Hollywood, was always about trying to fit into a version of brown people or Muslims or Indians. They were writing characters that were so stereotypical and whatever, and Sakina’s Restaurant was in response to a lot of that. It was so rare at that time to even get to see these particular type of characters told truthfully.

Before Sakina’s Restaurant, Indian people did not go to the theater to see themselves. They went to the theater because they were like, “Well, it’s a really important play. It’s by George Bernard Shaw,” or “It’s by Tennessee Williams.” They had no reference for, like, “What do you mean there’s a play about me and my experience? I’ve never seen that before.”

There’s something always spiritual and magical about it when I’ve performed it. It just felt like it came out of a completely truthful expression of my creativity.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Aasif Mandvi for sharing this creative journey with us. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you heard things in it you can bring into your own work.

Maybe it’s the way Aasif’s mentor, Wynn, shared his dream and championed it — even when Aasif himself wavered. Maybe it’s the way Aasif found different allies at different stages of his journey, who shared his dream for different reasons. Or maybe it’s the specific way a ringing telephone raises the stakes — and brings a scene to life.