Turn memory into art

How do you write the stories of your life? Any time, any place, any order. Isabel Allende was 39, and a refugee from her native Chile, when she started writing a letter to her dying grandfather – recounting the family stories he’d told her – of love, loss, memory, magic. This letter evolved into her first novel, the beloved epic “The House of the Spirits.” With her trademark warmth and wit, Isabel shares how she found the time and space to write as she rebuilt her life – and how her 500-page typed manuscript, heavy with correction fluid and coffee stains, found its way to the agent in Madrid who made it an instant international sensation. Throughout the story – told entirely in Isabel’s brilliantly chosen words – you’ll hear never-before-told details about her creative process and journey, including ideas on story structure and writing rituals; first readers and family politics – all of which can fuel your own story-telling.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: A broken life

- Chapter 2: The phone rings

- Chapter 3: The letter becomes a book

- Chapter 4: The history I was trying to capture

- Chapter 5: 500 pages

- Chapter 6: The first readers

- Chapter 7: Turning memory into characters

- Chapter 8: Nobody wants to read this thing

- Chapter 9: How you train to be a writer

- Chapter 10: The things I carry

Transcript:

Turn memory into art

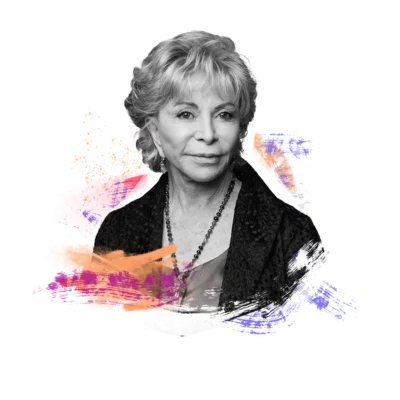

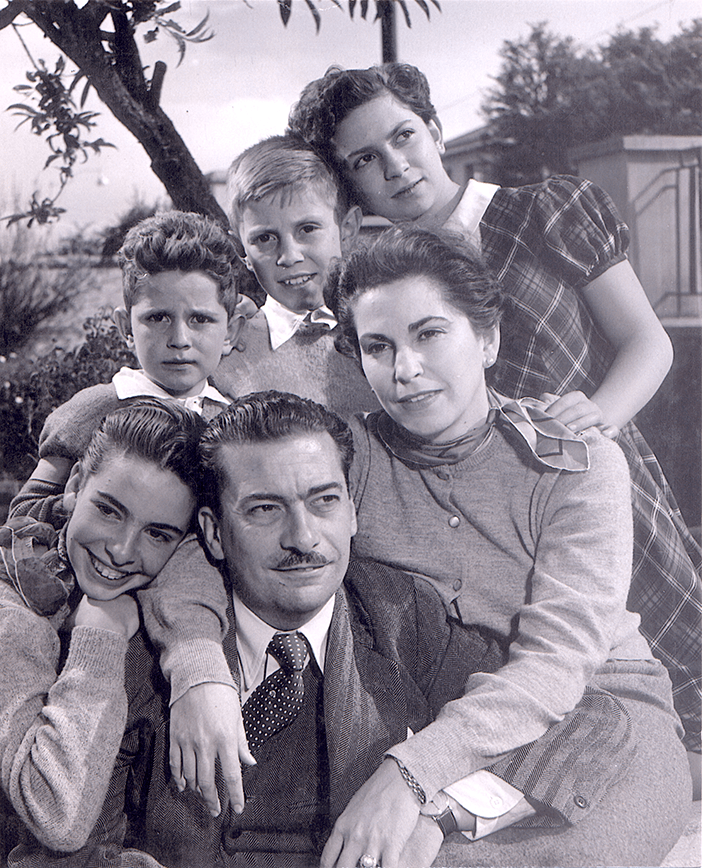

At age 39, journalist Isabel Allende found herself uprooted, in a strange country, full of family stories to tell. All images courtesy Isabel Allende except as marked.

Chapter 1: A broken life

ISABEL ALLENDE: The difference between being a refugee and being an immigrant – and I have been both – is that a refugee has been forced to leave and is always looking back, looking at the past. An immigrant is someone who has left on their own volition, and they want to create a life somewhere else. They don’t look at the past, but at the future. My relationship to Chile was always this love-hate affair, this nostalgic anxious desire to understand and to go back to recover what I had lost.

The first spark to write The House of the Spirits wasn’t even in my mind, it was a feeling. It was a feeling of loneliness, of nostalgia, of being 39 years old with no purpose for the future and with a broken life.

JUNE COHEN: That’s novelist Isabel Allende, and she’s about to tell us the story of writing The House of The Spirits. It was the first book she published, and it was an immediate international sensation. A bestseller first in Spanish, and then English. But like many works of great art, it was born from great loss. Isabel was forced to leave Chile in 1973, after the coup that brought Pinochet to power.

She was living in exile in Venezuela when she started writing The House of the Spirits.

So it’s a very specific story about a writer capturing the stories and the style of her family in Latin America, during tumultuous political times. But the themes are universal, for anyone in any field who hopes to keep memories alive.

As Isabel begins writing, you’ll hear her channel ancestors to help her tell the story. And you’ll hear her wrestle with relatives who weren’t thrilled about what she told. You’ll hear her focus on human truth when she didn’t have all the facts. And you’ll hear the specific rituals she builds around her writing, to create momentum for herself. They’re ideas you can use in any field.

Here’s what you need to know about Isabel Allende. She’s written more than 25 books that have sold more than 75 million copies. But it all began with The House of the Spirits. And this book began as a letter to her dying grandfather – home in Chile while she was exiled in Venezuela.

As she wrote, the letter evolved into the sprawling epic we know, which tracks a fictional family through four generations – before and after a coup in a country that’s never named.

Isabel started writing The House of the Spirits on January 8th, 1981 – almost exactly 40 years before we released this version of her story. You’ll hear details here that have never been shared before.

The piano you’ll hear in the episode is our composer Hil Jaeger, who’s playing along with this story.

[Theme music]

Chapter 2: The phone rings

ISABEL ALLENDE: My mother got the call. She lived three floors above us, and she came down. My mother was crying, and she said, “Papa is dying.”

I never got to talk to him. He hated the phone, absolutely hated the phone, and I couldn’t go back to Chile to bid him farewell, but I would write to him frequently. So I said, “Okay, I’m going to write to my grandfather.” But my mother said, “He won’t receive the letter, he’s dying.”

It was late. On January 8th. We had eaten, and the kids were watching TV. I went to the kitchen, there was no other space to write in the house. And on the kitchen counter, I started the letter for my grandfather in a small Underwood typewriter that I had at the time.

I had been raised the first few years of my life in his house. We were very, very close. To the last day that I left Chile, I visited him every single day to have a cup of tea with him. So we talked about what? We talked about the past, about stories. He was a man that would never gossip about other people. So if I would come with a story about a neighbor or somebody, he would say, “If you are not sure, don’t repeat that.” That was for him a point of honor, so we couldn’t gossip.

We never touched politics because we knew that that was something that would be a fight. He was very conservative, but he was a democratic man. Feminism was another thing that we couldn’t discuss. He was just the maximum patriarch, but a good one.

We also talked about the telenovela because we were both watching something terrorific, that dark nights … I don’t remember the name, but it was just vampires and zombies, and we talked about that a lot. And the stories of the family, that was our ongoing conversation for a lifetime. He was a great storyteller.

And in that letter, I want to tell my grandfather that I remembered everything he had told me, that he would go in peace because I was the guardian of his legacy. I remember the first sentence, that didn’t mean anything in a letter for a dying man. The first sentence is, “Barabbas came to us by sea.” Barrabas was a dog we had at home, that he had. A huge dog that looked like a horse, was a Grand Dane. Why did I start like that? What did I want to tell him about Barrabas? I have no idea. I think that that book was just dictated to me, probably by my grandmother. So I started that letter without knowing that it would grow, like an octopus with tentacles, and become something else.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how Isabel reflects on how she wrote? She believes it was dictated to her by her grandmother. And of course that’s beautifully consistent with the book’s magical style. But maybe there’s something we can all take from that idea. Maybe one of the keys for turning memory into art is imagining an ancestor by your side.

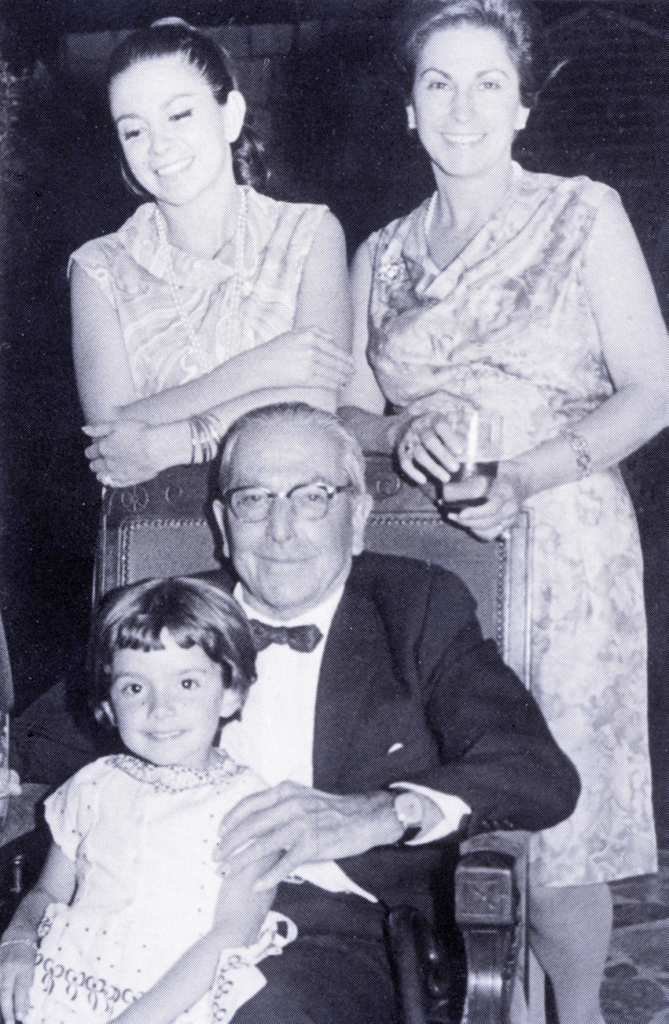

Four generations of family, with Isabel Allende at upper left, her own mother, Panchita, at right, and her grandfather holding Isabel’s daughter, Paula.

Chapter 3: The letter becomes a book

What do you do if you don’t know all the facts? Focus on the human truth.

ISABEL ALLENDE: All these stories would come to me like waves, and I had to put them down immediately. I wrote, like, in a trance, without organizing it in my mind, without a structure, without a plan.

I started with the first story that he ever told me, which was the story of my great aunt Rosa, that was my grandfather’s first fiancee. And she was supposed to have been very beautiful. And she died poisoned before they would get married. The circumstances of that event are not clear in the family. I never knew if it was an accident, if she committed suicide, if somebody on purpose poisoned her, we don’t know. I don’t know, but it doesn’t matter because the storyteller doesn’t need to know the facts. The storyteller needs to know that human motivations, the feelings, the consequences of some action.

There was no structure. There was no plan. I wanted to write all these stories, but they were not glued in my head in some kind of order. I would make mistakes all the time. So I used a lot of Tipp-Ex. Tipp-Ex was a white liquid that we used to correct, because there was no computers. So you would put the page in the roller of the typewriter. And if you made a mistake with this liquid, you erased the word and then you had to wait until it dried completely. And you would type on top of it.

Before digital composition tools, this was Ctrl-Z: a bottle of Tipp-Ex, Wite-Out, Liquid Paper, brushed on with a tiny applicator. Once applied, you must wave your hand over it until it dries completely, or your corrected papers will get stuck together. If you are a certain age you can smell this picture. (File image.)

Suddenly I would want to explain more about something that I had written many pages before. So a lot of cut and paste because the only way you could insert a paragraph by cutting a piece of paper and taping it there. So before you wrote anything, you had to think, it was one take. That created a tension that was extraordinary.

So the manuscript – it was a mess, plus I was writing in the kitchen. So often it had some tomato paste or coffee. I mean, I cleaned as much as I could, but sometimes things happen.

500 pages with a lot of Tipp-Ex has some volume. So I carried this back and forth in a canvas bag. That bag was precious to me because there were no copies, absolutely no copies. I never let go of the canvas bag. I would go to the office with my bag because I didn’t want to lose it. I remember that once I left it in the hairdresser, and I almost died because it was a Saturday afternoon, and it was closed. And I had to wait until Monday to see if it had appeared.

I would write at night, and I would write on the weekends. I don’t remember what my family thought I was doing. They never asked because I was always writing letters. They had seen me writing, sitting at the typewriter all their lives. So for my children to see me again sitting at the typewriter didn’t mean anything. I don’t think they even noticed.

I didn’t realize at the time, but I was doing it – that by writing about the micro universe of the family, I was creating the macro universe of the country, as what was happening to the family was happening to the country. At the end, both things, like, matched, but I didn’t plan it.

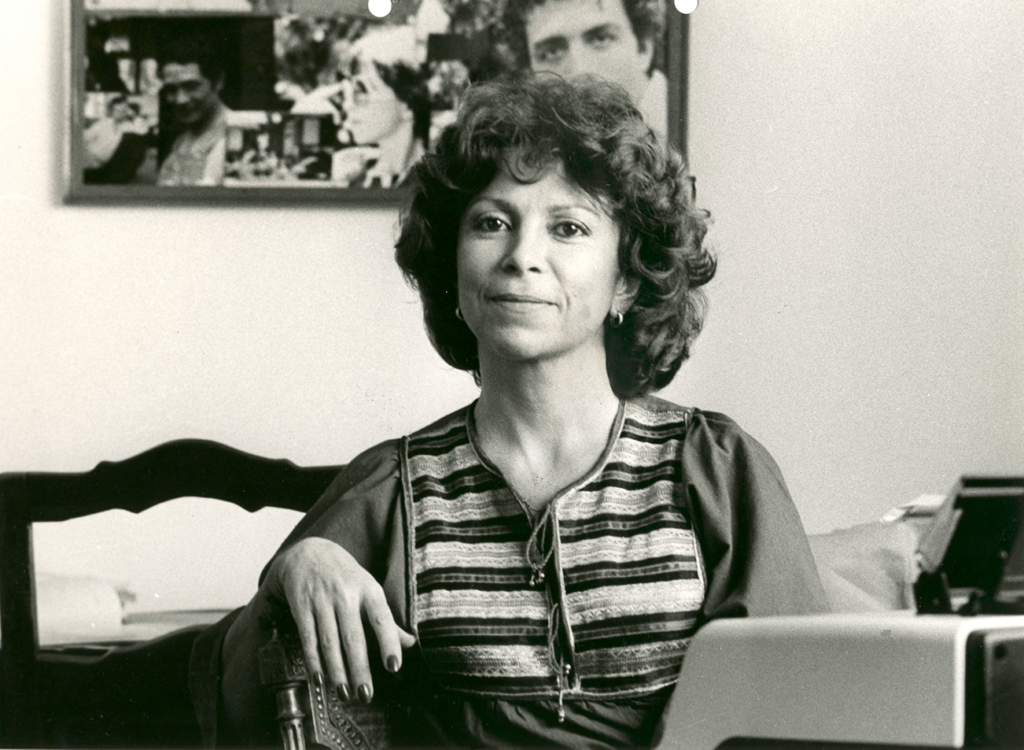

Isabel Allende at her typewriter.

Chapter 4: The history I was trying to capture

ISABEL ALLENDE: As a young woman in Chile, I had two kids in a tiny house, two dogs. I worked in a women’s magazine. I owned my life. That’s what I thought. And that changed in 24 hours.

I got up as I usually did, very early in the morning. Got my kids ready for school, and I took my car and went to my office. And I noticed that the streets were empty. There were some people stranded waiting for buses that never came and a lot of military vehicles in the streets. The feeling of emptiness of something in the air.

In 1960s Chile, Isabel Allende was an established journalist working at magazines and on TV.

I arrived at the office, and the office was closed. The guy that was at the door said, “Go home, go home. This is a military coup.” And I said, “What? What’s a military coup?” “Go home.” I went to a friend’s house to use the phone, and she was desperate because her husband, who was a teacher, had left very early in the morning and had not come back. I knew where the school was, and that was downtown Santiago, very close to the presidential palace. And I said, “I’ll go and pick him up.” When I got to the school, I found him in one of the classrooms, listening to the radio and crying. He was listening to the last words of Allende. He told the people that he would only leave the palace dead.

Salvador Allende was a first cousin of my father. He was a very charismatic, strong, courageous man. His idea was to have a change to socialist without a revolution, which had never been done before. So the eyes of the world were looking at him.

And then very shortly after, we saw the airplanes, and they were bombing the palace. The presidential palace was an icon of democracy in Chile – it still is today. And then we had curfew for three days. People were hanging on rumors because there were no news. On television, it was only orders from the military, the generals. When we started to hear what was going on and we could get out, then we saw how scary it really was.

We had seen people disappear. I had gotten people to find asylum in embassies. I had been smuggling information, I had been hiding people at home. I was warned that I was on a list, and I better get out. And so I got out thinking, okay, I’ll come back in a couple of months. But then my husband started finding out that, no, I couldn’t go back. So then he left with the kids, and we reunited in Venezuela.

I remember those years as the worst. We didn’t have any money, we didn’t have documents. And then the struggle started, the struggle to make a living, to make a family, to adapt, always without unpacking, mentally, always with the idea that we would go back soon. So what’s the point of doing anything permanent in Venezuela if we are going back? The dictatorship lasted 17 years, and that’s a generation.

A glimpse of the life she left behind: In 1960s Chile, Isabel Allende wrote for Mampato Magazine, a children’s magazine; she also wrote for and appeared on television, interviewing authors and other notable people. “I was always typing,” she says.

Chapter 5: 500 pages

How do you keep your memories from fading? You write, and you write, and you write.

ISABEL ALLENDE: I felt that I was forgetting. I was forgetting – not only people and my country – but the stories were becoming more blurred. So I could remember the plot, but I couldn’t remember the music of it, the tone, the intention, the irony, the inflection of the voice. That was gone.

At the beginning, a letter. And then I didn’t know, maybe it was some kind of memoir, like trying to remember. But there was a point when I knew I was writing fiction because everything that I was writing was based on members of my family or anecdotes from my family. But they were fictionalized.

I can’t remember in which moment I thought, “I’m writing a book.” I don’t remember, but there must have been a point when I did. The process took a year. No one read a page, no one knew what I was doing until it was done.

There’s a sentence in one of Bertolt Brecht’s plays in which the character more or less says, “I am that man that goes around with a brick to show the world how his house was.”

When I finished the book, I felt relieved. I felt that I had, finally, everything down. It was not going to be erased by oblivion. I could go around showing to myself or whoever wanted to know what my house, my country, my past, my memories, my family had been. And I felt that those 500 pages were my brick.

JUNE COHEN: Did you find yourself picturing Isabel with that brick of a manuscript – stained with tomato sauce and heavy with Typex? And did you also find yourself wondering: If Brecht had his plays and Isabel has her book, what is my brick?

After the break, Isabel shares the mistake she made – that you can still find in the first edition.

The memory of her family, centered on her grandfather, drove Isabel Allende to “write and write and write.”

Chapter 6: The first readers

When should you show your work? When you’re ready to change it.

ISABEL ALLENDE: My mother read it. And then my two children, and those were my readers.

First comment, my mother didn’t even say, I like it or I don’t like it. She said, “How could you give the name of your father to the villain?” I said, “Mother, he’s called de Bilber.” She said, “Yeah, your father’s second surname was de Bilber. His mother was de Bilber.” And I said, “Well, I must have heard it when I was a child. But frankly, I don’t recall knowing this.” And my mother said, “This is so insulting.” And I said, “First of all, he abandoned the family. So who cares? But if this is important for you, I’ll change it.”

Now try to change a name when you don’t have a computer, and you can’t say “find and replace.” You have to go, you sit your two children at the dining room table, and you go page by page with a ruler, very fast. And if the name appeared, they would give me the page. I would be sitting at the typewriter with Tipp-Ex, type the new name, which had to be one letter shorter than the first one, because it had to fit in the space, so we did that with 560 pages. But we skipped one, so the first edition of The House of the Spirits has a de Bilber floating there that nobody knows who the heck this character is. That was corrected later.

Paula was a very good reader, my daughter, because she had been in a nun-school, and for her, grammar and spelling was like the structure of life. So she was very, very serious about that.

My son, who was a teenager, read it. My son said, “Mom, here you have characters that are 18 years old in page 20. And in page 240, they’re still 18. And several years have gone by.” He has an engineer mentality, like his father. And so he created a chart. First, he started on a board, on a blackboard, and then it was too complicated. He ended up mapping it on a large piece of paper with pencil so that we could move things around and erase and then write it again.

As I was correcting the book, he would change the things in the map that he had made. Or I would, for example, talk about an earthquake. And Nicolas would say, “Which year was the earthquake?” I said, “Nico, there are no years in the book, it doesn’t matter.” He said, “No, but it matters because it relates to the election. So how much time happened between those two events?” That’s the kind of thing that my son would notice immediately. And there was a moment when he looked at it, I couldn’t even see it, but he will look at it and say, “Now it makes sense,” he would say.

He has done the same chart for each one of my books because I tend to write without thinking. And he says, “Mom, look, that day there was not a full moon.” And I say, “Who cares?” “I care,” he says, “and there will be one reader that cares. So why don’t you change the moon, what’s the problem? Change the moon.”

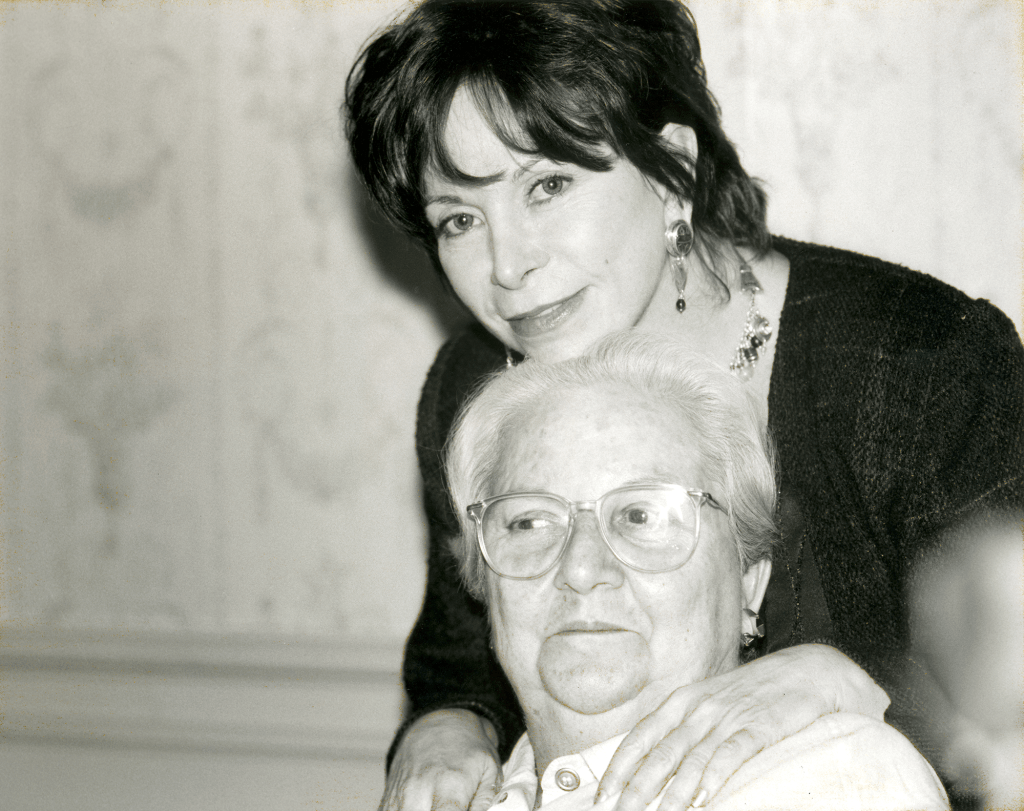

Isabel’s first reader was her mother, Panchita, who lived three floors above her in Venezuela. Her first reaction: “How could you give the name of your father to the villain?”

Chapter 7: Turning memory into characters

How can you preserve the people you’ve loved? Capture their luminous qualities – and invent the rest.

ISABEL ALLENDE: It didn’t occur to me that I could pick up a character and just drop it and forget it. I decided, “What would happen with that person? I have to finish the story.”

I was filling-in information, paragraphs. I was cutting what was extra, things that didn’t contribute to the story, and things that I couldn’t pick up later and make them have meaning.

At the beginning I kept the names of members of my family, and then I changed the names because I thought, wow, they might get angry. And actually, even when the names changed, they did get angry at the end. But some of them didn’t speak to me for like 20 years.

I kept the names of Luis and other people in the book, Aunt Rose, Tia Rosa. I kept her name. My grandmother was called Isabel, like me. She was clairvoyant in the book. I didn’t think of her name. I thought, “Ah, I don’t want my name in this,” and so I decided to change it. Then I started thinking, “How do I remember my grandmother?” And I remembered her like this luminous being that was almost not human because she was so special. She’s Clara in the book. In Spanish, Clara means light. It was like the natural name.

I have so many theses of students about The House of the Spirits, and one of the thesis’ is about the names. And the poor guy spent a year analyzing the names to discover that all the names in The House of the Spirits mean something about the character. Esteban in Spanish means rod, and the main character, the patriarch, is a rod. Pedro means rock. Clara means light, so all the names mean something, and he said, “Except Jaime.” And he said, “Why Jaime doesn’t mean anything?” And I didn’t have an explanation because I didn’t think of the other names. I chose the names at random, completely at random. It just happened that way.

Isabel Allende and her children, who (as teenagers) were among her first readers – and editors. They helped her tame the manuscript, replacing character names and Tipp-Ex-ing phrases as the manuscript grew and grew.

Chapter 8: Nobody wants to read this thing

What do you do when you can’t find your way? You let yourself be discovered.

ISABEL ALLENDE: Now, I didn’t have any hope that it would ever be published. My mother thought that it was a book, and she said, “Okay, I don’t know if this is a good book or not, but let’s try.” She sent it to several publishers. Nobody answered.

The only person who answered was the secretary of one of the publishing houses in Venezuela. She was called Virginia. Virginia called, and she said, “Look, nobody’s going to read this. I’m telling you, nobody knows you, it’s too long, you’re a woman. You need an agent.” I didn’t know that agents existed for literature. She said, “The best agents are in Spain.”

Carmen Balcells, who was this larger-than-life woman, visionary, generous to the extreme, tough as nails, was a literary agent at the time of Franco in Spain, when censorship was rampant. For 40 years, publishers would prefer to publish books that somehow were not controversial, that would not bring any anger from the government.

Carmen realized that there was a bunch of extraordinary writers writing in Spanish and didn’t have to go through the censorship. They were in Latin America. So she convinced the publishing houses in Barcelona, mostly, to start publishing them. And if they couldn’t be distributed in Spain, so be it; they would be distributed in the rest of the world.

We found the address. We went to the post office – the manuscript was too heavy. They said, “No, we have to cut it in half, and send two envelopes,” so we did. I wrote a first page of introduction, in one or two paragraphs what the book was about and who I was, and I sent both together, but only the second part arrived. She didn’t pay much attention to it. She liked the writing but she didn’t know what this was. It didn’t make sense; it started in the middle of nowhere.

I had lost hope. I thought, “Nobody wants to read this thing.” A month and a half later, the other part came. After she put both parts together, she called me.

She was so respected and feared. If she said to me, “I’m going to have this book published,” it’s because she was sure she could do it. She was sure she could do anything, and she would never promise something she could not deliver, never.

I was so thrilled that it was going to be published. Oh, that was incredible, that there was a publisher that was willing to invest in this manuscript. I was grateful for every detail, every new thing. I wasn’t expecting anything.

She invited me for the launching of the book. I didn’t know that books were launched at all. I arrived in Barcelona with a huge, old suitcase, and my husband.

She was throwing out a party for me as if I was a celebrity. She invited the critics, the inteligencia of Madrid and Barcelona. This is the only time in my life I have seen a bowl of caviar served with a ladle.

She was beginning to serve dinner, and she was going to make a toast, and in that moment: No electricity, the lights went off. It was pitch dark and Carmen, without missing a beat, she said, “These are the spirits that have come to toast with us for this book.” That’s the woman she was – full of magic.

She would read my astrological chart, and she said, “You’re a genius according to the stars.” And I said, “Carmen, let’s prove it here, in this world first.”

She would say to me, “We are not friends. I am your agent, and you’re my client.” But she would cry if something bad happened to me. She was not my friend? Give me a break; she was my best friend.

Isabel Allende with her agent, Carmen Balcells, who first championed the book. “Carmen Balcells … was this larger-than-life woman, visionary, generous to the extreme, tough as nails.”

Chapter 9: How you train to be a writer

What’s the secret that makes creativity flow? You make a full commitment.

ISABEL ALLENDE: I was in Spain for only a few days, went back to Venezuela to my old life. And the idea of making money with writing never crossed my mind. And the truth is that I couldn’t quit my job, for financial reasons. I kept on working in the school and forgot about it. I did not forget what Carmen had said, that I needed to prove myself with a second book.

And by January 8th I started another book, the same date I had started the previous one.

A book is a full commitment, for me it is. It’s like falling in love, like getting married. You invest in it everything you are, all your time, all your energy, your creativity, everything. So to make that commitment is scary. And unless you are passionate about something, a theme or an event or something that you want to tell, why would you do something like that?

So let’s say that I have an idea that I want to write: a memoir about being a feminist and being a woman. Usually, I have finished the previous book two or three months before, and I have some time to research.

I start reading feminists. And then the memory of what happened, why did I become a feminist? I start calling my friends from then. I started remembering how it began.

I get all my documentation ready. And by January 7th, I clean up the attic where I write. So I take out everything that had to do with the previous book, and it’s organized and clean because it’s very small. I burn some sage because I want to get rid of the bad energy. Then on January 8th, I get up really early, I do some meditation, I light my candle, and I, as I would say, I open a vein. I just start, whatever will come.

Having a day to start forces me to find that passion inside somehow. And I know because I have the experience that it will take weeks before the book really starts, but I show up every single day. And I write, even if I know that everything will be deleted the next morning. Doesn’t matter. It’s part of the process. And I never give up. I have never left a book unfinished.

I always think of it like training for sport. You train and train and train to create the muscle. And, nobody cares how much you have trained and how much effort and suffering. The only thing that matters is the performance to get up there and play the game. So it’s the same with a book. You train and train and train, and delete and delete, merciless, and then suddenly, it picks up. Once you get the tone, you get the narrative voice, there is a moment, a magical moment when you know it’s coming. Slowly the characters will come out of the shadows.

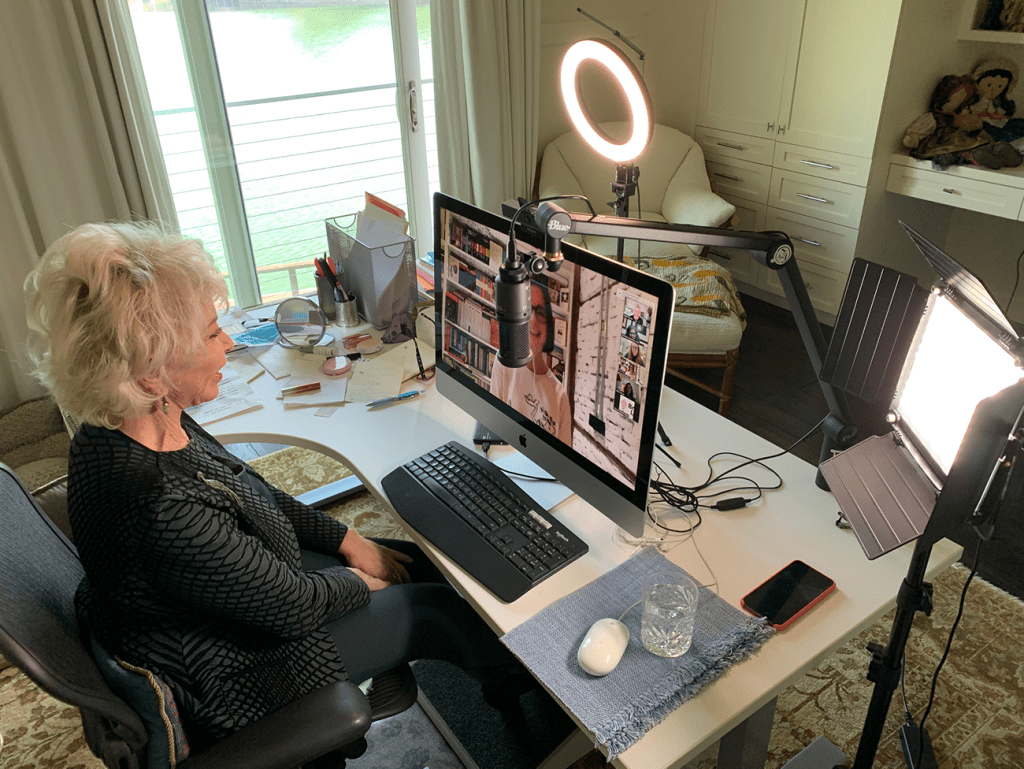

Isabel Allende sits at her typewriter in this vintage image. Throughout a life marked by change, this has been her constant.

Chapter 10: The things I carry

ISABEL ALLENDE: I am really, really, very close to my son. And after my daughter died, we became even closer because we are the family. There’s no more family. And he always was worried by the fact that I exaggerate. I lie. I tell complicated stories, that I remember what never happened. And there was a point and not very long ago that he said to his wife, he said, “Finally, I understand that my mother has a different brain. She thinks in spirals, in circles. She can’t think straight.” And I have no sense of hierarchy, no sense of straight lines, of angles.

For me, everything moves, is flowy, constantly, constantly changing. Nico understood it at one point, and he stopped bugging me about that. And so now I understand that he thinks in a very different way, and I totally admire and respect it, and he tolerates me.

I used to explain The House of the Spirits like a crazy attempt to recover all that I had lost. And I think I did. In a way, it’s all there, in those pages. It’s a wonderful gift. Something that the spirits of the universe gave me. It paved the way for all my other books. It gave me a voice. It changed my life. It created millions of readers that have been so loyal to me. All that, The House of the Spirits did. But most of all: It’s the brick that I carry around to show the world who I was and what my house was like.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Isabel for sharing the story of her creative journey. It meant so much to us to capture it. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you found things in Isabel’s story that you can bring into your own work.

Whether it’s the way Isabel identified that feeling that she was forgetting – and turned her family memories into art. Or the way she’s created a ritual around writing to ensure she keeps momentum, year after year.

It might be the way Isabel’s creative journey blends the family she’s lost with the family around her – channeling her grandparents as she writes, and her children as she edits. Or it might be the way she focuses on human truth more than the facts. But she’s always willing to change the moon.

Isabel Allende in 2020, speaking to an audience on Zoom. It’s been almost exactly forty years since she sat down to write a letter to her grandfather that turned into her beloved book.