Cultivate a child’s sense of wonder

How do you create deeply imaginative work? There’s a method behind the magic. As Rian Johnson (Last Jedi, Looper, Brick) takes us on the journey of joyfully reinventing the murder-mystery, you’ll hear the way he draws on childhood memories (like watching Agatha Christie movies in his grandparents’ rambling old house) to inspire his work. You’ll also hear he rigorously structures his creative process – including when, where and how he writes – in order to be playful and present when he shows up on set. Within this story, you’ll hear tactics (and lots of creative techniques) you can borrow to fuel your own creative journey, whatever your field.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: The first spark

- Chapter One: The first spark, revisited

- Chapter 2: Let’s make a movie – fast

- Chapter 3: A cabin in the woods

- Chapter 4: Zoom in, zoom out

- Chapter 5: Designing a detective

- Chapter 6: A fast start

- Chapter 7: What I knew from the beginning

- Chapter 8: Make it visual

- Chapter 9: We arrive on set

- Chapter 10: A font with nightmares inside

- Chapter 11: The moment of truth

- Chapter 12: Whodunnit

Transcript:

Cultivate a child’s sense of wonder

Director Rian Johnson on the set of Knives Out, whose interiors were filmed in a century-old mansion outside Boston. The script draws on Rian’s childhood memory of another old house, his grandparents’ place in Colorado – where he and his 30 cousins staged epic film shoots every summer. Photo: Claire Folger/Lionsgate

Chapter 1: The first spark

RIAN JOHNSON: God, like third grade. Me and the neighbor, Josh, who was a little older than me, we were planning a movie we were going to make: a Godzilla-type movie about this monster gargantuan. I had my Star Wars figures and we were planning it out and we were playing the shots and the stunts and everything. My dad, who was in the construction business, had gotten some wooden beams, big tar-filled beams, and he had built a massive sandbox. In my memory, it was a massive universe of sand. It was probably like five feet by five feet.

Then one day, I was like, “Come on, man, let’s go.” And Josh had had a rough day at home or something and he was down and I was the annoying little kid saying, “Oh, why don’t we work on this scene?” He goes, “Man, we’re never going to make a movie,” and he kind of walked off. I feel like that almost sounds like a super villain origin story.

“Someday, I will make the movie. I’ll show them all.”

JUNE COHEN: That’s “Last Jedi” director Rian Johnson, and he’s about to tell us the story of writing and directing “Knives Out,” the genre-busting mystery he’s been thinking about ever since that first creative spark in the sandbox. But wait, was that the first spark? Or was the first spark a different moment in Rian’s Childhood?

Chapter One: The first spark, revisited

RIAN JOHNSON: I remember being in my grandparents’ house in Colorado, most beautiful house in the world. Their bedroom upstairs is where the VCR and TV was, and my dad had the VHS copy of “Sleuth” with Michael Caine and Laurence Olivier, written by Anthony Shaffer. It takes place in one house. All my uncles and aunts and little cousins and I, we would all gather around on the couches, and it was a special thing to put on a VHS tape and watch a movie together.

Even more than the movie, I remember the impact that the movie had on the grownups in the room around me when I was watching them, and feeling like, “Wow, this is something that’s holding these people’s attention and really affecting them.” So much of it goes right back to that.

JUNE COHEN: As we move through the making of this beloved film about a family in a mysterious house on a hill – keep your ears peeled for clues on that initial spark that inspired it all.

Rian Johnson is about to tell us the story of writing and directing “Knives Out.” It’s the specific story of joyfully reinventing the murder-mystery genre – on a super-fast timeline. But it’s also a universal story about cultivating a child’s sense of wonder to drive great creative work.

As Rian takes us on the journey of creating “Knives Out,” you’ll hear the way he constantly pulls from childhood memories – and tries to recreate those magical feelings in the film. You’ll also hear how he meticulously builds rigor and structure into his creative process in order to show up on set present and playful. And while Rian’s specific field is film, these are tools you can use in any creative field.

A few things you should know about Rian Johnson: He’s written and directed five feature-length films, including “The Last Jedi.” And as he tells us the story of creating this mystery, you’ll hear him reference Agatha Christie’s iconic fictional detective Poirot, and the “Knives Out” Detective Blanc, played by Daniel Craig.

The original music you hear is our composer Hil Jaeger. And for visuals while you’re listening – go to sparkandfire.com/knivesout.

[THEME SONG]

In 1972’s Sleuth, Laurence Olivier and Michael Caine explore a mystery that’s set within one sprawling old house. As a child, Rian Johnson was amazed at how this movie – with its story by Agatha Christie, and script by Anthony Shaffer — could capture the attention of the adults around him.

Chapter 2: Let’s make a movie – fast

How do you get a quick start on a project? Pick up the idea that you couldn’t let go.

RIAN JOHNSON: We had just finished the Star Wars movie. We had finished “The Last Jedi.”

Ram Bergman, my producer, and I both had the instinct of it would be really great just to make a smaller movie quickly, just to do something right away, as opposed to putting together another huge project or whatever. Let’s make a movie.

Honestly, “Knives Out” because it had been hanging around in my head for so long, it was the thing that was most ready to go. I’ve had ideas that have gone the way of the Dodo that have just not survived that peter out. “Knives Out” stuck around, not because I tended to it or watered it almost becomes this house guest that won’t go away. Didn’t really make it any easier to write.

God, it would be nice if you just tucked it away in the back of your head and it just slowly grew and then you had it fully formed at some point. Not the way it works. The reality is the house doesn’t get built until you buy the lumber and start putting boards together. It wasn’t until I actually sat down and started to work out, “Okay, so how do I actually beat this thing out into a story, into characters?” Unfortunately, that’s no less work after you’ve been thinking about the basic idea for 10 years.

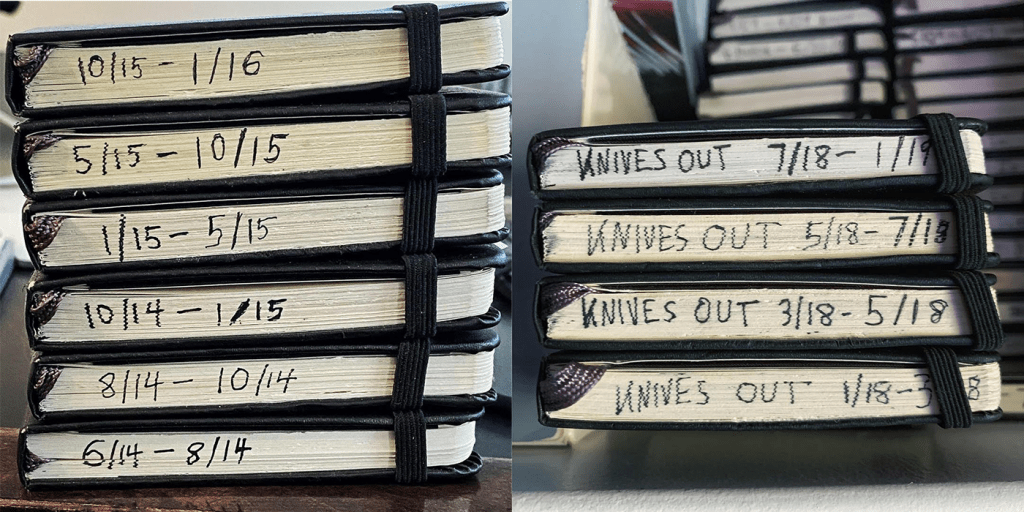

Imagine opening any one of these Moleskine notebooks and a script pops out fully written. Unfortunately, says Rian Johnson, that’s not how it works. He’d been kicking the Knives Out story around for at least 10 years in his notebooks, along with other projects. The stack of Moleskine notebooks on the left? That’s The Last Jedi.

So I sat down and started trying to write it.

There was the initial implanting of the murder mystery forum is the scary adult genre and it’s something that I just loved. The next step was thinking about whodunits and thinking about what works about them and what doesn’t work so well. There’s a little bit of “Okay, we’re gathering more clues. Okay, and they have another murder happen just to keep things going.” But there’s a certain point where you’re just like, “Okay, let’s get to the point where the detective explains it to us because we know we’ll never be able to guess it.” That led to this notion that, “Well, okay, what if I did a whodunit, but I really fabricated the plot in a way that would suit a movie where you can’t just be gathering clues. You have to have a protagonist who is in danger that we worry about and have the mechanics of a thriller.”

So the audience thinks, “Oh, it’s been subverted. And we’re, ‘okay.'” Then you’re along for the ride and still have the payoff at the end that I want of the detective in the library explaining it all to us. And “Oh, ah ha, this and this and this and this.”

A whodunit had been hiding underneath that thriller the whole time. I didn’t even have a story, just that concept was the first thing that got me excited about, “Okay, this could be something worth doing.

Chapter 3: A cabin in the woods

How do you get creative work done? Remove distractions and create rituals that work for you.

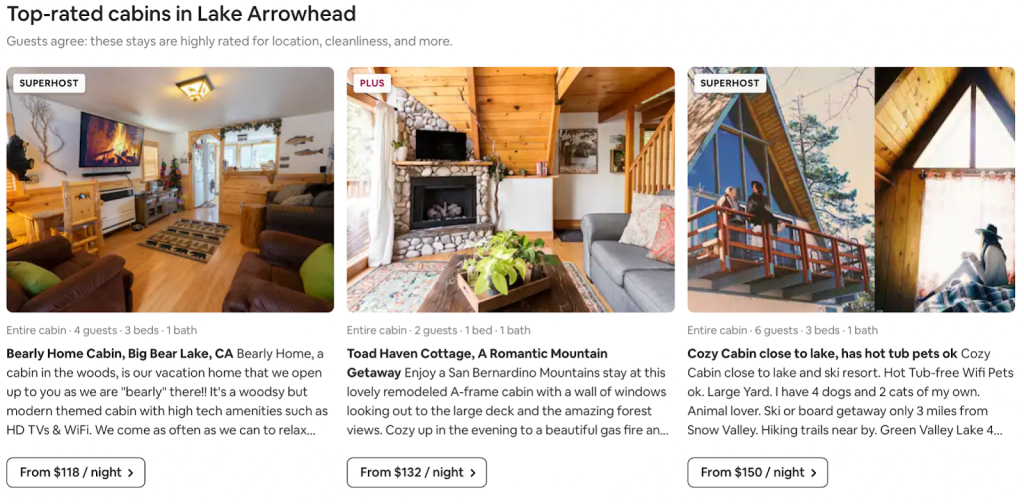

RIAN JOHNSON: I had to get a bunch of pages written. I went up to this cabin in Lake Arrowhead that I’ve been Airbnb’ing for the past 10 years. It’s become the place I go to when I need to just type and get it done, to the point where my brain is hardwired. When I’m in that cabin, I write. It’s this weird, magical thing. My producer loves it. He’s like, “Hey, maybe we should buy that cabin for you.”

Saving you a click, here is the Lake Arrowhead, California, rental page on Airbnb. Pack your Moleskines.

I have all the typical, horrible things that writers have when they’re supposed to be working. We procrastinate and we goof off. At the same time, anytime an external thing comes into our space that threatens the time we’re supposed to be writing, we get very angry at it.

I’m generally not a grumpy, kind of angsty person, but there’s a reason I go to a cabin in the woods to write. No one wants to be around me. It’s a bit like being in a deep sleep and having someone nudge you. It doesn’t feel great.

I usually do listen to music when I’m writing, but that has to be music that I’ve listened to a thousand times so that it can fade into the background.

I listened to LCD Soundsystem’s album, “Sound of Silver,” on a loop eight hours a day. For some reason, that album just became kind of this spell that I had to have going in order to just make my fingers work and write. Once I’m actually locked in, there is a thing where you do get in the zone and kind of the rest of the world sort of goes away.

JUNE COHEN: As Rian describes his writing rituals, did you start to notice the method behind his magic? The specific location, the specific music to create an almost magical spell. And this is the theme you’ll hear again and again in Rian’s story, which you can bring to any creative field. There’s a disciplined process that allows him to play.

In the next chapter, you’ll hear the structure Rian brings to the writing itself. And as he tells you about the story arc he draws in his notebook, keep in mind: It’s an actual visual arc. if you want to see it, go to sparkandfire.com/knivesout and follow the visuals there.

Chapter 4: Zoom in, zoom out

How do you make the best decision on every small detail? You keep your eye on the big picture.

RIAN JOHNSON: I work in these pocket-sized Moleskine notebooks. That’s how I’ve written for years and years and years. I’m a big structure guy when it comes to writing. That’s the way that I can get my head around it. I need to know the limits of the chess board before I can start moving the pieces. I need to be oriented.

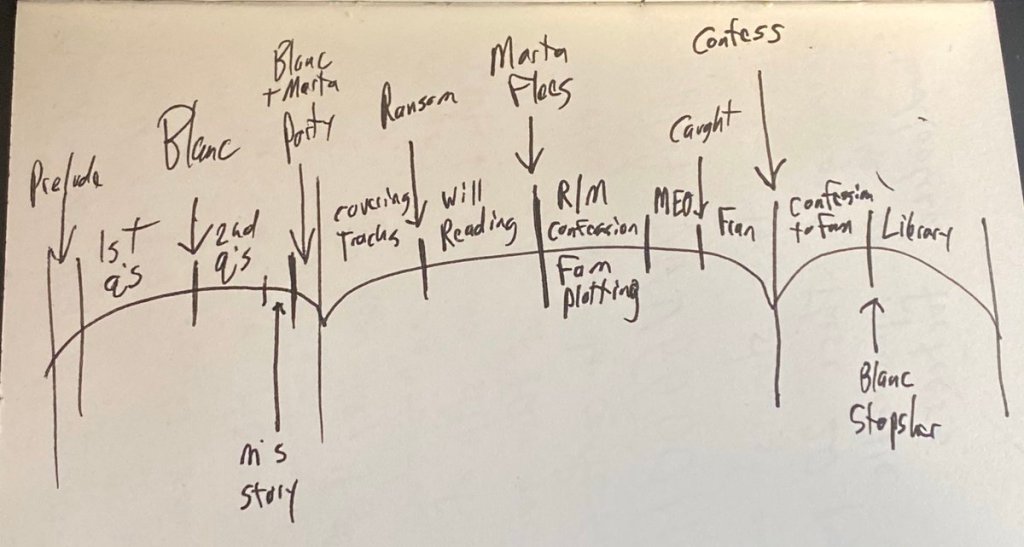

The first 80% of the process is not writing scenes or dialogue or anything. It is just drawing diagrams and outlines and notes, mapping out the story and how it’s going to work. I have to start zooms back and then slowly zoom in bit by bit. And the reason for that is so I can understand first, the purpose of the movie. First, literally, where does the movie start? Where am I trying to get to by the end? This conceit that I have in my head, how does that fit into say three acts, or how does that fit into an arc that I draw on a small piece of paper that is the movie?

There’s not a ton of detail there. The same way you wouldn’t draw every tree on a map. It’s just the path and you can see how it lays out. Then I’ll break out and do one arc for an act so that I can get into more detail about, “Okay, how does this actually flow?”

“This is how I always diagram stuff out before I start writing.” Rian Johnson tweeted this story arc from one of his Moleskines.

And then I zoom into sequences, which to me are like 10 to 12 minute chunks of scenes that there are a couple of in each act. Each thing works in relation to the thing that it’s next to – never thinking about scenes in a vacuum or sequences in a vacuum, but always thinking about them in terms of what’s propelling us into it. If a story feels like it’s working, it should feel like when Tarzan is swinging on vines and the propulsion of one vine launches him into grabbing the next and the arc of the next one. It has to be an active handoff between them.

The idea is to never lose the big picture orientation so that when I get down to the granular details of characters and their motivations and their feelings in their scenes, I can be making those decisions all based on a compass that’s pointed towards the destination of the story. That’s the way that I’ve kind of always done it. That’s kind of the only way that I can, otherwise I’ll get lost in the forest.

Chapter 5: Designing a detective

How do you create a cast of characters? Look for how they fit together.

RIAN JOHNSON: The problem with sitting down and saying, “I want to write an iconic detective,” is that your frame of reference is other iconic detectives. So you’re thinking, “What is it about Poirot that I think of?” Now of course you think of his accent. You think of his weird fussiness. You think of the different people who have played him in their quirks they brought to it. And those are the wrong things. That’s not how you build a character.

For me, I realized I had to throw away the whole notion of eye patches or peglegs or whatever I was going to give him, and just start writing the story and find Blanc’s place in it. Actors are never going to want to work with me after hearing this, but the characters are going to be designed to be gears in this machine. I very rarely come up with characters first. The character for me is something that I come up with according to the needs of the story. Each character does serve a purpose.

You need a broad spectrum of people that we actively dislike, people that we like but then become disappointed in – each of these characters is a fragment of that personality of the movie. If you think about kind if you sat on a shrink’s couch and all the different fragments of yourself, of your own mind regarding a certain issue and all the different ways you feel about it and all the different ways you feel about it that you wish you didn’t feel about it, that you want to work against because you want to be a better person – all of those different things, but all kind of lining up to one coherent personality, those are the characters.

I tend to come up with them in pairs usually, in terms of diametrically opposed attitudes or energies, and then you try and get them in scenes where they play off of each other. Like the character of Richard, who’s played by Don Johnson in the movie, who’s sort of an affable jerk. There’s a way that Richard feels which is in contrast to the other characters to, for instance, Toni Collette’s character, Joni, who is awful in her own way, but has a completely opposite energy of Richard. In a way, those two are the opposite poles. You have to build a character based on their function in the story and their actions that drive that story forward. That’s what defines who they are, is their actions in the story.

Gears in the machine: The extended family of “Knives Out,” assembled in the Ames Mansion. From left to right. Richard (Don Johnson), Linda (Jamie Lee Curtis), Ransom (Chris Evans) Great Nana (K Callan), Marta (Ana de Armas), Harlan Thrombey (Christopher Plummer) Walt (Michael Shannon), Jacob (Jaeden Martell), Donna (Riki Lindholm), Joni (Toni Collette) and Meg (Katherine Langford) in Knives Out Photo Credit: Claire Folger

JUNE COHEN: As Rian describes how he creates characters, did you find yourself projecting his methods into your own work? Even if your field isn’t film, there may be a convention you’re pushing against – the way Rian pushed against Agatha Christie’s Poirot. Or there might be a way you harness opposing forces in your work – Rian does it by pairing characters, for you it might be something else.

After the break: Production starts moving fast, like jump in a speedboat fast.

Chapter 6: A fast start

How can you help a project move at double speed? Don’t second-guess yourself.

RIAN JOHNSON: I was typically a really slow writer. I’ve taken like years to write scripts before. And “Knives Out” was the first one where I honed in and got the thing written in about six months or so, which for me is really, really fast. Because it had been in my head as this mythological thing for so long, you actually get the thing down on paper. And now that it’s real, is it still interesting?

I remember saying to Ram even after I got the first draft done, “Do you think this works? I don’t know. I can’t really tell.” I’ll feel not good and I’ll feel good again. You know how it goes. It’s dah, dah, dah, dah, dah. It’s an endless rubber banding of, “This is the best thing in the world. This is garbage. This is terrific. Oh, I’m ruined.” It’s just that constant zigging and zagging between those two extremes. And yeah, and that’s what we call dancing.

Once I wrote the script, we were like, “I don’t know if we’re going to get anyone in time. Are we even going to be making this movie?” I was on like a week-long vacation with my wife. We were at a beach resort and I got the call from my producer, who said, “I need you to go meet Daniel Craig up in New York tomorrow.” And so I literally got on a speed boat to go catch the first flight out. I felt like James Bond going to meet Daniel.

And then once Daniel said yes, everything happened right away. He had a very specific window before they got into shooting the next James Bond movie. Suddenly we were in Boston and we were scouting and we were casting all the other parts. And it was just this mad rush. In a way though, I think that that’s what helped us get such a great cast. The game of casting is always like, “Are you available eight months from now?” And their agents are always like, “Well, they are available.” But then in the back of their head, they’re thinking, “If a Marvel movie comes up or something, can we get out?” With this, it was, “Can you show up in a few weeks and have fun in Boston making this murder mystery?” Honestly, because this was so much quicker, I guess I just didn’t have the fundamental faith in the script that I usually do.

But the nice thing about it all going so quickly is you don’t have time to worry about that. You don’t have time to be nervous about it. You’re thrown into the pool and you have to swim. And so suddenly you’re dealing with the day to day questions of, “Which glasses? These or those? Which location, this one or that one? Which actor, this or that?” And you kind of just step up to the wheel and start driving.

Talking through a script while on set in Berlin, Mass., director Rian Johnson, at far right, explores a scene with actors Chris Evans, left, in sweater, and Ana de Armas. Photo: Claire Folger/Lionsgate

Chapter 7: What I knew from the beginning

How do you learn what makes something great? Go so deep in the classics that you memorize why they work.

RIAN JOHNSON: One thing that I was always completely confident of is that people will want to see this type of movie. And maybe it goes back to being a kid and sitting on the couch and seeing all the adults in the room react to it. I think more than that though, it just goes back to being a kid and just loving those movies. There’s nothing more fun than “Evil Under the Sun” or “Death On the Nile.” There’s nothing more fun than that kind of movie. These are films that I watched largely as a kid that felt very adult to me at the time. It’s the same with Agatha Christie’s books. It’s a form, it’s a genre. It’s a thing that I don’t know. I think we all have affection for things that we perceived as being incredibly adult when we were much younger.

I have friends who have watched a billion movies, watched every movie in the world. I’ve seen much fewer movies, but I’ve seen them all 30 times. I watched the same movie over and over and over and over again: “Miller’s Crossing,” “Topsy-Turvy.” “Treasure of the Sierra Madre” is one that I just watch over and over. “8 ½” is another movie that I’ve seen so many times.

A movie that Rian Johnson returns to again and again: John Huston’s atmospheric masterpiece Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

I have such a horrible, horrible, horrible memory. I find that repetition kind of necessary to implant things in my brain and to get deeper into something and to really start to parse why it works. The truth is I’m making it sound more academic than it actually is. If there’s something that I’m sitting down and watching over and over, it’s like listening to a piece of music. It’s not like you’re trying to identify something technical in it. It’s just because you enjoy it and there’s a pleasure to it.

The sense of being absorbed in it never goes away no matter how many times I watch it, but what does happen is I begin to memorize it the way that you know a room that you have slept in for 10 years. You begin to memorize sensory details from it and how it feels cutting from one shot to another, how the music feels when it sweeps you through a series of shots. Those begin to become second nature to you in a way that’s similar to when you know a piece of music really well. It’s muscle memory. And I think you get that from watching movies and making them. That’s the only two ways you get that.

Chapter 8: Make it visual

What if there’s something creative you just can’t do? Sometimes, you do it anyway.

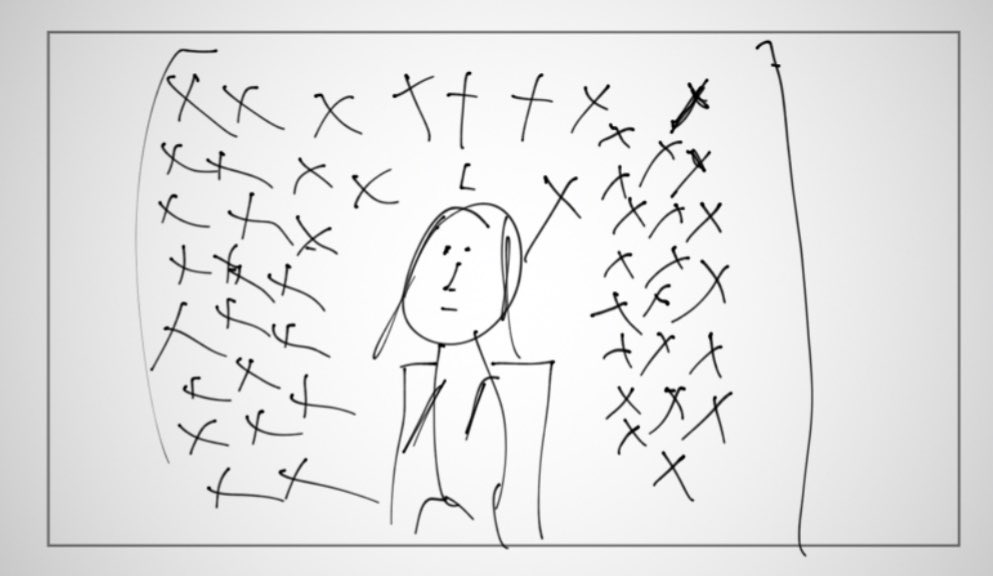

RIAN JOHNSON: I can’t draw. I really wish I could. I do my own storyboards. And so I do a lot of drawing and I keep thinking I should get better at it and I feel like I’m actually getting worse. My drawing is just pathetic stick figures. And it’s more for me to just kind of go through a process where I watch the movie in my head and write it down.

So if I want to think, “Okay, this type of framing, this reflects this thing that’s going to happen later on in the movie,” or, “This shot will call back to that shot,” or, “Okay, we’re developing kind of a visual idea or a motif.” Storyboarding allows me to do that.

And then Steve, my cinematographer, and I will sit down and I’ll take him through the storyboards. Because they’re nearly indecipherable, I’ll have to actually translate them for him. But that’s part of the process. It’s a step because I have to describe to him the intent of each shot. And Steve, actually he’s come to really like the fact that my drawings are horrible because they don’t communicate any extraneous information. They don’t give any lighting, they don’t give any mood. All they give is composition and the intent of the shot. And that’s great because we can then have a conversation about how we can actually achieve the mood and the lighting, and that’s a whole other conversation on set.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how Rian never questions his ability to draw meaningful storyboards – even though he can’t draw? In fact, he embraces his limitation as a tool of empowerment for his team. And this is exactly how kids work when they make art together – before the world convinces them of what they can and can’t do.

Above, Rian Johnson’s actual storyboard; below, what the scene ended up looking like. Ana de Armas and Daniel Craig in “Knives Out.” Photo: Claire Folger/Lionsgate

Chapter 9: We arrive on set

How do you set the right tone when you collaborate? Prepare, prepare, prepare – and then watch for happy accidents.

RIAN JOHNSON: The director does set the tone on set. If the director seems comfortable and chill and creative and open, it just very naturally, leads to a set that feels that way.

Part of the work is doing the work beforehand. Getting to a place where I’m not panicked when I show up on set and I feel like there’s a plan. That lets me be comfortable. So when I show up on set, I can feel that way and I can project that.

Pre-production is something that is not covered in a lot of behind the scenes stuff and it’s not talked about a lot, and it’s where so much in the movie actually gets made. And the majority of pre-production, you’re in a crappy rented office and you’re in boring meetings all day long, going through lists of props and lists of things, and it’s even harder to stay inspired. But that’s part of your job is just stay focused on the story and to be able to look at spreadsheets and look at these presentations from these different department heads and keep your eyes open for moments that you can make work for the movie.

There wasn’t a lot of time for me to get too granular in terms of the props, but it was such an embarrassment of riches in terms of what they found that on the day, it was like a constant game of, “Okay, grab that, then put it there. Let’s get that into frame. Grab that. Oh, we can use this thing for that thing. And we can get that skull in the background of this and it will line up with that.” So things like that, you find on the day and you spot it. And they’re like, “Oh.”

There’s a shot where Harlan is confronting Joni. We kind of dolly around his desk and in the foreground, there’s this little sculpture that they had found, which is a mom with a kid over her knee and she’s about to spank him. And it kind of pivots around on this perfect little sculpture of this kid getting spanked while he’s taking Joni to task.

Enlarge this photo and spend a few minutes marvelling at the brilliant clutter on Harlan Thrombey’s desk in this scene with Ana de Armas and Christopher Plummer. Items from among this clutter – a mug, a baseball, a statue – create their own plot points. Ana de Armas and Christopher Plummer in “Knives Out.” Photo by Claire Folger

It’s being able to strike that balance of being open to finding things on set while at the same time, keeping your hands firmly on the wheel. It’s fine to let go into different tangents and conversations and figure out different stuff, so that can lead to magic as long as you’re making sure that it’s serving the master of what the scene’s basic purpose is.

It started with that first scene, you start with a very dramatic shot of the house. And the next thing is this kind of cheesy birthday gift mug that someone gave Harlan at some point – “My rules, my house, my coffee” – coming down, which lets the audience right away know it’s a contemporary film and also wanting to kind of break the tone a little and indicate to the audience that there’s going to be humor in this movie. You know we’re going to have fun with this here. That mug started there and then it kind of tracked through.

And at some point in pre-production, I was like, “Well, maybe she has the mug at the end. Is that too cheeky? Maybe she has it.” And then it was literally while we were on the day filming it, we were in that closeup of her. She was up on the balcony. I was down the driveway and I shouted, “Take a sip from the mug.” And she brought it up and the words came up into frame, my house, and I was just like, “Ohhhhhhh.”

The iconic final image of Knives Out came together on set as they were shooting the scene. “Take a sip from the mug!” shouted Rian from the ground below the balcony.

You’re fishing every day. With all of the stuff you’re juggling in your head on set and all the demands. Part of your work is to stay creatively present so that you can be inspired by things you see on set in a way where you can find happy accidents like that.

Chapter 10: A font with nightmares inside

RIAN JOHNSON: When I was a kid, I remember being in my grandparents’ house in Colorado and just kind of scanning their bookshelf for something to read and seeing Curtain, this paperback version of Curtain by Agatha Christie, and this particular edition of Curtain has a very scary looking cover. And then it has a painting of Poirot, but he’s a scary version of Poirot, and he has a slightly mysterious expression. There’s something about him and the whole thing that just feels so… It’s like the line in “Spinal Tap:” “It feels like death.” Especially for a kid. I don’t even know how old I was, just kind of looking across the shelf, this thing jumped out, just the word, “curtain.” It really struck me and it felt like it possibly held nightmares inside of it. The cover is completely just black with this very striking font, which I copied for the “Knives Out” title font. Pulling that book off the shelf and reading it was kind of my hook into Agatha Christie and to kind of mythologizing this genre of the murder mystery.

The movie poster for Knives Out lifts the font from this edition of “Curtain,” with its delicious serifs like peaks in an evil meringue. The font works in many alphabets.

Chapter 11: The moment of truth

RIAN JOHNSON: That first test screening, it’s terrifying. There’s nothing scarier than putting it in front of a group of people who are not your friends, and who you don’t know, and everybody who put money behind the movie is sitting there with you staring to see if this thing works or not. Everything about it is terrifying and scary and awful. The opening prelude, there’s not a lot of laughs in there and so you’re kind of holding your breath in that first act when Don Johnson points to Blanc and says, “Well, who the fuck is that?” The audience lost it. You’re still kind of holding your breath for those scores to come back. You still kind of don’t even trust yourself.

And then by the end of the film, in the denouement, when they were still with it and still engaged on that level, I knew that we had them. It was one of those things that until then I had only read about. The lights go down and we had the audience from the opening moments and it was just the most genuinely happy experience I’ve ever had in a theater. We got the test scores and they were insanely good and it just felt bizarrely positive. It almost freaks you out more because you’re like, this is not supposed to go well like that. And we did make changes to it and we made cuts along the way, but it felt good from the very first screening of it.

It feels strange to… I feel more comfortable being in a position of learning from failure, I guess. This happens very rarely. You have to allow yourself to enjoy that when it happens.

It’s strange that after you finish a movie, the place that that movie takes in your head. Every single time I would do a Q and A, and I did a lot of Q and A’s for the movie, and every single time I would get there a little early and I would go in and I would watch the last half hour of the film and genuinely enjoy it. And even movies I’ve made that I’m very, very proud of this was different. This is like, is like oh, you know what? I feel like the thing that I loved as a kid, sitting and watching “Evil Under the Sun” or watching those mysteries with my family. Yeah. All right. Okay, cool. If I can sit down and actually enjoy this in that way, maybe we got a little bit of that on screen and that feels really good.

Chapter 12: Whodunnit

RIAN JOHNSON: I have a huge extended family, a lot of cousins. I’m the oldest of 30 cousins and we’re all really, really close. And we would all have our vacations together. And while we were on these vacations, it became a tradition that we would make a movie. And my cousin, Nathan, who is now my composer, and I would plan out and shoot a movie and use all of our cousins as the actors and the crew basically.

And one of the ones that we did was set in my Nana’s house and the name of the movie was “Pandora’s Box.” And it was these two guys who live in this house and the mysterious stranger shows up and says, “There’s a treasure somewhere in the house and it’s a box and if you knock three times on it, dance on one foot, and say ‘woogah woogah’ the box will open and the treasure will be revealed.” And of course my Nan and Grandad’s house is full of boxes. And so it ends up being this thing where the two guys start looking for it and then it’s kind of like “Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” where they start fighting. And of course at the end they get in a big fight and accidentally blow up the house.

My grandparents house, the house that they’ve had for years, it’s a big house and it’s full of antiques that they got in Europe. And so the whole house has a slightly Gothic feel to it. My memories of the house are literally scary cuckoo clocks on the wall and dark velvet wallpaper and pictures and portraits of old relatives who I didn’t know who they were hanging on the walls all around us. It just kind of has that feeling of, in children’s literature, of the magical mansion the kids are sent away to for the summer. It really does have that in my head.

There was a room upstairs where when all of us were staying there for Christmas, there was a bed that we called the coffin bed because it was a bench that folded open and then there was a bed inside of the bench and it just looked like a coffin. And so in the room upstairs, who’s going to sleep in the coffin? It had so many different layers of that. There was this terrifying antique wooden carousel horse in the living room. Details, details, details, just layered through the house.

Willa Cather has a great quote where she says, “Most of the raw material a writer works with they accumulate before they’re 15.” And I think there’s real truth to that. I mean, I’m realizing now of course, kind of the insight, I guess, the house in “Knives Out” is probably – of course it is – it’s my grandparents’ house. There you go.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Rian for sharing the story of this creative journey with us – all the way up to the final reveal. And I want to thank each of you for listening. I hope you found things in the story that you can bring into your own work or practice.

Whether it’s the way Rian mines his childhood memories for inspiration in his work or the way he turns his own creative limitations – his distraction, his stick figures, his memory – into a playful springboard for his creativity.

Or it might be the method behind his magic: The way he meticulously sticks to a creative process that works for him – in order to cultivate that sense of wonder.

“The magical mansion that kids are sent away to for the summer.” The Ames Mansion in Massachusetts, where Knives Out interiors were filmed, has a fascinating story in its own right. As the interior set for Knives Out, it became a detail-packed mystery box, a locus for characters to connect and the truth to emerge. From left: LaKeith Stanfield, Noah Segan and Daniel Craig in “Knives Out.” Photo by Claire Folger