Transcript

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

5 strategies for starting something new

CHRIS McLEOD: That was novelist Ann Patchett, teasing her strategy for getting started on a new creative project — which you’ll hear in full a bit later. In this episode, you’ll hear from five different creatives in five different fields offering five different strategies for how to start something new.

Every creative endeavor starts with a spark. We hear about these moments of inspiration in every episode of Spark & Fire. But truth be told, that’s the easy part. All you have to do is be inspired. But then there’s an intimidating blank page or blinking cursor staring you down. Sometimes, actually starting is the hardest part.

Well, today on Spark & Fire, we’ll be a fly on the wall as creative icons look that blank page in the eye, and get moving.

I’m Chris McLeod, Executive Producer of Spark & Fire. I spend most of my days inside the stories of our guests, and I’ll be the host for today’s episode.

So I guess there’s nothing left to do but start! Here are 5 strategies for starting something new.

Our first strategy takes on the only real enemy there is when you’re having trouble getting started: your own mind. With an adversary like this, you’ve gotta get sneaky. Novelist Ann Patchett knows how to trick herself into getting out of her own head so that she can actually start.

Strategy 1: Sneak up on your work

ANN PATCHETT: I’m a very, very bad starter. I’m strong in the middle, and I’m a fantastic finisher, but I’m a terrible starter.

Who wants to sit down one morning and say, “Today, I am writing the opening sentence of a project I will be on for, I don’t know, two years or something”? I have an idea; I have the book all plotted out. But then when I actually start to write it, I think, I have no idea what I’m doing. I don’t know how to transfer idea into writing, that’s always where I get stuck. And then I sit down one day and say, “Okay, well, this isn’t going to count, but write a paragraph. Go ahead, just write a paragraph. Just throw it away tomorrow. This isn’t the real start.” And that’s how it starts. I’m sneaking up on my novel. I’m coming in very quietly sideways.

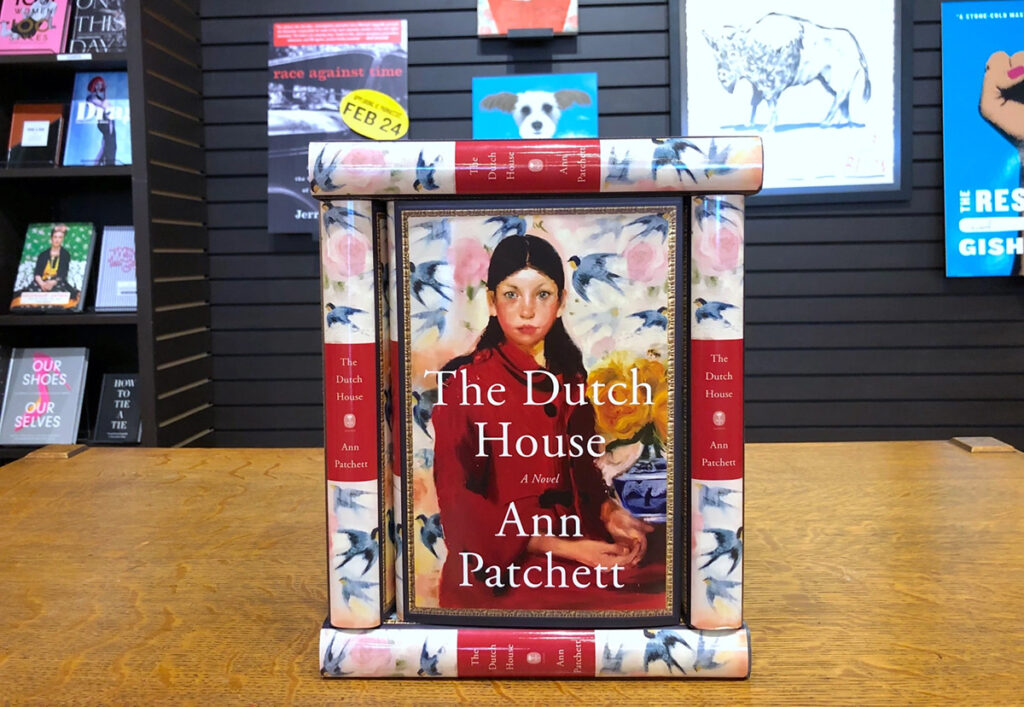

The Dutch House stands on a table at Parnassus Books, the bookstore Ann Patchett co-owns in Nashville.

CHRIS McLEOD: My favorite thing about this strategy is how un-precious Ann is with her beginnings. If you heard Ann’s full episode, then you know how many times she rewrote her novel The Dutch House because she was terrified of anyone reading a bad book. But Ann understands that being precious isn’t the way to get started.

Our next strategy also concerns the elusive mind, but it’s about when to simply turn it off. It comes from Pixar director Domee Shi. Domee had been working at Pixar for years as an animator and storyboard artist. After she was given the chance to turn a really weird idea about a mom and a dumpling into a Pixar short, she got an even bigger opportunity.

Strategy 2: Don’t think. Just draw

DOMEE SHI: The president of Pixar, Jim Morris, invited me into his office. First, he said, “Congrats on the short. It’s amazing and weird and cool, and we want to see more from you. Would you want to pitch some ideas for a feature film?” And I said, “Yes.” I was like, “Thank you, thank you. Thank you for the opportunity.” And then I calmly walked out, and then I speed-walked to Rosie Sullivan’s office, who’s my good friend, closed the door. And then I freaked out in front of her, and I was like, “Oh my gosh, they just asked me to pitch an idea for a feature. Ahhh!!!!” And I rolled on the ground freaking out, and she freaked out with me. And she also got on the ground like, “Oh my God.” And both of us are just like, “Ahhh!!!!”

I didn’t even have any feature film ideas. Sometimes I just try to draw my way out of getting stuck. And it’s better for me than just sitting and thinking. I’ll just start drawing who I think the main character could look like. I’m figuring it out as my hand is moving. I have something tangible to work with.

So I was sitting on my busted Ikea couch with wobbly legs drawing in my sketchbook. My boyfriend, Darren, was sitting next to me, and I was, like, sketching. I would show him. I was like, “What do you think of this?”

It was a drawing of a girl. And she had this giant backpack on, that was crammed full of textbooks and school supplies. And she had her flute case under one arm and a tennis racket under the other. And then I would sketch this red panda design that came from this magical amulet that her mom gave her for her birthday, and that was weighing down on her neck as well. And she looked really, really stressed out, like the weight of the world was on her shoulders. And maybe I was feeling that too a little bit at the time, or always, I don’t know.

And I turned into the story about a tween girl named Mei-lin Lee, who thinks she has her life completely under control when suddenly, boom, magical puberty hits one day, and she turns into a giant red panda anytime she gets emotional, angry, and worked up. And her mom wants to quickly get rid of this red panda so that her daughter can stay her perfect little girl.

A grab from Domee Shi’s sketchbook, where she experiments with styles and moods. See the whole page on Domee’s Instagram.

CHRIS McLEOD: Truth be told, drawing is not my personal strong suit, and maybe it’s not yours either. But this strategy of not thinking, and just creating, can thankfully be applied to any field. For me, I’ll sit down at a piano or pick up a guitar and just play.

Our next strategy is about seeing the big picture before you begin. It comes from legendary Broadway composer Stephen Schwartz. When Stephen was writing the musical “Wicked” with his collaborator Winnie Holzman, even before he started on a song, he had a strong idea of how it would serve the greater story. Stephen looked at his outline and saw a moment at the end of the first act that needed a song. He knew exactly how to begin.

Strategy 3: Start with the title

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: I always like to start with the title of the song, to define for myself: how does that title embody a moment in the story?

From my very first outline: “At the end of the first act, she flies.” Once Winnie had written script pages for it, the first thing I did was make a list of possible titles,

And I called Winnie. I read her a list of six titles; one of the titles was “Defying Gravity.” And Winnie said, “I think I like that one.” And I said, “Good, because that’s my favorite.”

Long before I knew it was time actually to write songs, I started jotting down little fragments of melody, or chord patterns, and then I would just put them away. About a year and a half later, I went back to look at these little scraps of paper with shards of melody or chords. I discovered things like this: [piano plays]

I also had a melody that was like [piano plays]. I think I also had that big jump. That’s all that was there.

Once I had the title, and I kind of had this tune, I was able to write it really quite quickly.

The only thing that changed was when we cast Idina Menzel as the Wicked Witch. When I was teaching her the song and I got to the last verse, which is when she flies, the original tune was the same tune as the first two verses. It was [singing] “So if you care to find me, look to the Western sky,” and Idina said, “I’m flying at that point. Can I just stay up on a high note?” And I just said, “Well, you have to sing it eight times a week.” And she’s like, “Oh, that’s all right.” And so it turned into [singing] “So if you care to find me, look to the Western sky.”

Composer Stephen Schwartz learned when to put his inner editor back in the cupboard. Photo: Nathan Johnson

CHRIS McLEOD: Hearing how the song “Defying Gravity” came together is almost as magical as the song itself. It’s amazing how Stephen can approach each individual piece as a tiny creative journey, yet stay zoomed out enough to know how it’s fitting into his grand vision for the project. It’s like building a long yellow road, brick by brick.

Our next strategy for how to start something new is about generating great ideas. When you’re just starting out, there are endless possibilities, but that’s actually the problem. Endless is way too many.

Designer Thomas Heatherwick was given the task of creating a sculpture for new development in Manhattan. Thomas and his team didn’t know yet what they’d be making, but they knew it wouldn’t be a sculpture at all.

Strategy 4: Decide what not to do

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: When my team and I sit down at the beginning of a project, and I know this maybe is going to sound bad, but we start by deciding what we don’t want to do. And I know there’s this view of creativity as a beautiful, smiling, positive thing. Often, you have no idea what you are going to do or what you might want to do, but you can be clear what you really feel is the wrong thing to do. And that jumps you forward. That negativity is phenomenally positive.

We were on the 19th floor of one of the towers at Columbus Circle, meeting the founder and the client team for the Hudson Yards project. I don’t like the feeling of meeting boardroom table things. So I try to do everything I can to not sit face to face across tables like that.

And you’re just there thinking, oh really, am I going to say this thing? I don’t even know this person, and I’m about to kind of put a spanner in the logic.

“Right, we’ve got a space. What should we do with this space? Oh, what’s been successful before?”

“Did you see what they did in Chicago?”

“Oh, well, in Chicago, there are some incredible monumental works. Where the Millennium Park was created was very successful. There are a couple of really amazing works of art there. “

I initiated a line of conversation and questioning saying, “Are you sure you want to do what I think you’re asking for? Because isn’t that actually a very familiar format?

So many cities copy the formulas of other cities in the belief, Well, that is successful so it would probably be successful here.

Whereas my belief is, the most successful things say, “Bravo, fantastic. I love what you did, right? How do we do something with a similar level of ambition here, but not the similar formula? If I was you, I wouldn’t do a freestanding thing you walk around and sort of admire.”

And I was almost trying to get myself out of the door.

That conversation grew from something which originally might’ve felt like “this is something to wriggle out of,” but the positive response from the team it related of saying, “well, yeah,” and real recognition, a sort of spark in the eye and a response that was so encouraging that made us feel that there was space for something that could maybe be extraordinary – not for extraordinary sake, but for the public’s sake.

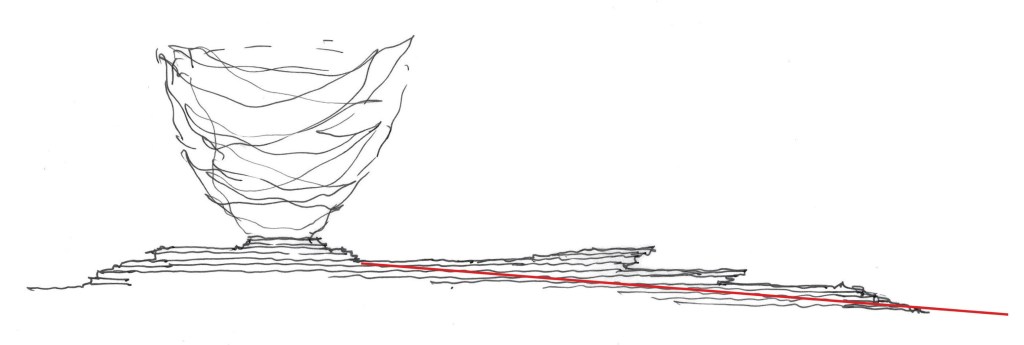

An early sketch of “The Vessel,” showing its placement on the sloping site of Hudson Yards, which tips gently down toward the Hudson River. Image: Heatherwick Studios.

CHRIS McLEOD: I love how Thomas has zero interest in doing anything that’s been done before. Not to diminish anyone else’s work, but he can look around at what’s already out there, and say “no thanks.” This strategy of deciding what not to do was a doorway for Thomas. It led him and his team to an idea unlike any other.

If you heard Thomas’ episode, you know they ultimately ended up creating an iconic piece of New York architecture called “The Vessel,” which is not only a piece of public art but an elaborate structure made of spiral staircases.

Our fifth and final strategy is probably the easiest way to get started I’ve ever heard. It comes from salsa legend Rubén Blades. Rubén discovered this simple method from his friend – the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Gabriel García Márquez, who he calls Gabo. When Gabo gave Rubén this tip, it ensured he would always have a surefire way to start something new.

Strategy 5: Buy a paper

RUBÉN BLADES: Gabo once told me, “There’s no such thing as writer’s block.” And I said, “Well, what do you do when you’re staring at a page?” He told me a story that you can actually go to the classified ads of a newspaper and see what people are selling. For instance, a bird cage for sale. And then you think, what happened to the bird? What kind of bird was it? Did the bird fly away? Did it die? What did he die of? Was he killed? Was he eaten by a cat? What’s the cat’s name?

All of a sudden you can write a whole story about what happened to that bird [laughs]. Yeah it’s like, you can just go on, and on, and on. Like Mort Sahl, the comedian, he went to a club, got the paper, opened it, and began to riff. That was it! So if you all of a sudden run out of ideas, buy a paper.

We have material all around us, so there’s really no reason why we should say, “oh I don’t know what to write about.”

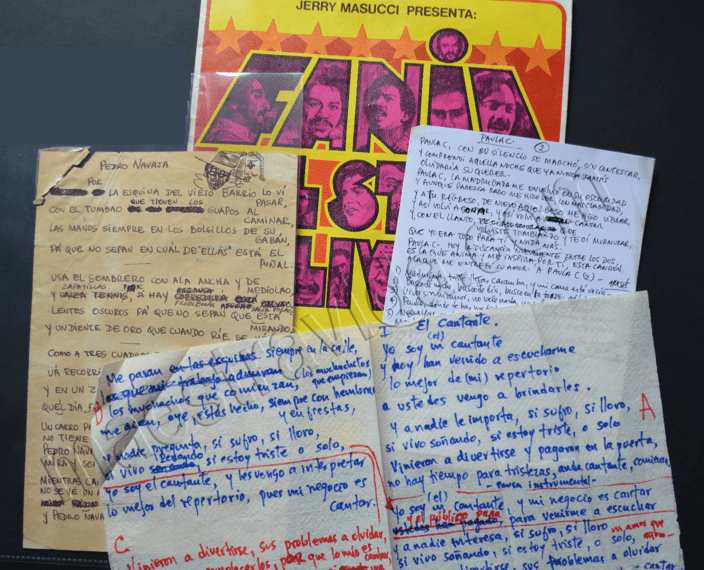

At the Ruben Blades Archives at Harvard, among the many feet of archival material, is a collection of handwritten song lyrics – including the first “Pedro Navaja.”

CHRIS McLEOD: Well, now I’m dying to find out what happened to that poor bird. Rubén’s advice to buy a paper shows that great ideas for a new project are truly everywhere.

We hope you enjoyed this episode of Spark & Fire, and found some things you can bring into your own creative practice.

Maybe it’s Ann Patchett’s mind trick of sneaking up on your project. Or how Domee Shi gets her own brain out of the way. We heard how Stephen Schwartz starts with the title. And Thomas Heatherwick’s method of first deciding what not to do. Or maybe what you’ll take away is the simple advice to buy a paper, like Rubén Blades.

Whatever you took from this episode, we hope it becomes a regular part of your own creative practice. To unlock your creativity, and start something new.

About the Creators and Host