How to recover your creative voice

What do you do when you fear you’ve lost touch with your creative voice? You let yourself feel it, and then open yourself up to inspiration. When comedian Patton Oswalt suddenly lost his wife, he also feared he would lose himself. As he processes his grief, Patton takes us on the journey of finding his voice again, through the making of two very different comedy specials: “Annihilation” and “I Love Everything.” You’ll hear how grief can give way to creativity — and creativity can forge a path through grief. With grace and humor, Patton recovers his voice by, first, opening his eyes to the world around him, and then, making himself available for the inspiration to come to him.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Something I didn’t know.

- Chapter 2: Shipwreck.

- Chapter 3: Exactly what I needed to hear.

- Chapter 4: How I got back on stage.

- Chapter 5: Relearning the craft.

- Chapter 6: Taping the comedy special Annihilation.

- Chapter 7: Ending a comedy show with Zen philosophy and porn.

- Chapter 8: Let’s see where it goes.

- Chapter 9: Let the muses find you.

- Chapter 10: Finding the bits for I Love Everything, at Denny’s.

- Chapter 11: What’s funny about being happy?

- Chapter 12: Taping the comedy special I Love Everything.

- Chapter 13: What I learned.

- Chapter 14: My advice to you.

Transcript:

How to recover your creative voice

Patton Oswalt in his 2020 standup special “I Love Everything.” Image: Netflix

Chapter 1: Something I didn’t know

PATTON OSWALT: Annihilation is almost like a — I don’t want to get all pretentious about this — but it’s a nice little document that shows that I can adapt to, and adjust to, and survive more than I thought that I could, because there were weeks and months after Michelle passed where I would’ve been very happy to have been annihilated, and not exist anymore. It wasn’t even a desire for death. It was absolute indifference to whether or not I lived or died. It’s really scary to have to face that. So, being able to make jokes about that was a … I don’t know. It really felt like, oh, you found out something about yourself that you didn’t know.

JUNE COHEN: That’s comedian Patton Oswalt. And he’s about to tell us the story of making two comedy specials: Annihilation and I Love Everything.

It’s Patton’s personal story of rediscovering his comedic voice after his wife’s sudden death — and channeling it into two very different hours of comedy. But it’s also a universal story on how grief can give way to creativity, and creativity can forge a path through grief, if you open yourself up, and allow others to carry you forward.

As Patton takes us on the journey of developing these two works, you’ll hear how — in the depths of his own despair — he found inspiration in other funny people. You’ll hear how friends and family, cast and crew, all helped him get back on his comedic feet and build creative momentum. Patton will also share some universal advice on what to do when your creativity just won’t flow — and how to start completely fresh on a new project and a new era.

And here’s what you need to know about Patton and his two stand-up specials. The first special, Annihilation, was released in 2017. It was the first hour of comedy Patton recorded after the sudden death of his wife, Michelle McNamara.

The second special is Annihilation’s polar opposite, which you can probably tell by its title: I Love Everything. This hour is about falling in love again, with his second wife, Meredith Salenger, and also the trivial things that give life texture — like the Denny’s restaurant franchise.

Patton has been a stand-up comedian since the ’90s, coming up in the alt-comedy scene. He’s starred in feature films and a bunch of beloved TV shows. Young children know him by his voice, as Remy the Rat in Ratatouille, and you might know him from an epic, eight-minute, completely improvised rant about Star Wars on the show Parks and Recreation.

But stand-up is the art form Patton always comes back to. So imagine his terror when he thought that chapter of his life was over.

I’m your host June Cohen, and on this episode, you’ll hear original music composed for piano and viola. For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com.

[Theme music]

While standup is his first love, Patton Oswalt is also a genre-spanning actor. He’s played a buddy role in the classic sitcom “King of Queens,” made a memorable cameo in the film “Magnolia,” personified evil in the dark satire “Veep,” voiced Remy in Pixar’s “Ratatouille,” and anchored the administration as Principal Durbin in the sitcom “AP Bio.”

Chapter 2: Shipwreck

PATTON OSWALT: April 21st, 2016. That’s the day my wife passed away. I had a new special coming out on Netflix the day before the tour that I was about to go on. The tour, everything had to be shut down because I was just in complete shipwreck and worrying about my daughter and worrying about her family. And I was trying to deflect all the terror that I was feeling.

I had these really surreal days where I was wondering, “Am I the one who died? Am I dead right now, and I can’t deal with the horror of myself dying, so I’ve created this scenario where it’s Michelle that’s dead, and I’m protecting our daughter?” I mean, I literally had these real psychotic episodes. I thought I had actually gotten to a higher level, because I wasn’t experiencing sadness. I also wasn’t experiencing anger or joy or fear. I wasn’t experiencing.

I said, “I’m just going to merely exist. I am going to wake up every morning, give my daughter breakfast, take her to school, park outside her school, wait until school is over, pick her up, bring her home, help her with her homework, make her dinner, go to bed.” That’s all I was doing.

I was like, “I’m done being a comedian. I’m never going to be a comedian again.”

Chapter 3: Exactly what I needed to hear

PATTON OSWALT: At that point, I’d been doing stand-up for almost 30 years. It was all I knew how to do. It’s been my main life force.

And if I can’t do the thing that brings me the most joy in life, then what kind of father am I going to be to Alice? What kind of friend will I be to my friends? What kind of brother will I be to my brother? I wanted to be able to function and live my best life for the people around me in the world. What do I matter in the world if this doesn’t work for me anymore?

A friend of mine, Michael Penn, gave me C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed. And I was going to a grief group and talking to other widows.

Then a friend of mine’s husband passed away and another friend of mine’s sister passed away. And I went into this dumb, egotistical self-spiral of: Have I become this avatar of death? Do I bring death to everyone I know?

I was shooting a TV series called Those Who Can’t. And the scene was with Susie Essman from Curb Your Enthusiasm. And I was telling her how I was feeling, and she just listened. And then she just went, “You’re not that important, honey.” And it was so funny, but it was, also, so exactly what I needed to hear. It kicked me out of it. It’s like, “oh wait a minute. Yeah, that’s right, life is so much more gigantic.” It was so freeing. And it also brought me back to what my wife always said, my late wife always said, which is: “It’s chaos, be kind.”

Michelle McNamara’s phrase “It’s chaos, be kind” has inspired hundreds of tattoos, from heartfelt scrawls to intricate flash art. From left to right: Andrew Bower; Josh Url and Inbox Tattoos; Serenity Body Arts; Matthew Limbers Tattoo.

She hated the phrase, “You know, things happen for a reason.” She’s like, “No, they don’t. No, they don’t.” It’s all random. We have no control over it. There’s no bigger latticework to it. And the only sanity and order you can bring to life is by being nice to people. And that’s it. That’s the only power we have.

This is getting into Oprah territory, but it felt like it was Michelle speaking to me through Susie at that moment, just going, “Hey. You make people laugh. All right. That’s fine. You’re doing your part. You don’t have the elixir to heal the world. You make fun of your dick on stage to drunks, and they’re happy for an hour. That’s actually pretty good. Go tell jokes.”

Chapter 4: How I got back on stage

How do you find hope if the pain won’t let you start? Find someone who’s a good hang.

PATTON OSWALT: It was literally not a spark of inspiration or creativity that led me to it. It was just trying to push against this death vibe that I was living with.

I remember reading Stephen King’s On Writing after he had that horrific accident. He couldn’t write for a while, and writing was something he did every day of his life. And the first couple times writing wasn’t about what he was writing. It was about, “Can I sit here again at the keyboard and hit the keyboard and make words come out?” I even think he says, “I can’t even remember what I wrote or what I was writing.” It was like, “Can I just sit here and write it again? Despite all the pain and all the disruption and the upheaval that I’ve gone through, can I still do this?”

There wasn’t some inspirational moment. And it had nothing to do with me doing material. I just wanted to go on stage and see if I could talk and exist. Like, can I get out of my house and go on stage? It was that crucial, and it was also that simple. It was that crucial, and it was that simple.

The first show I did that night was at the UCB Theatre. I feel like I want to say that I was nervous, but it would not surprise me if what actually happened was I didn’t feel a single thing. It was that automatic: I just want to go on stage and try to just get through this. It was really, really rough. I just cannot remember what I talked about. God, I couldn’t even tell you. God damn. I just went up and tried my best.

I remember a comedian named Emily Heller was on the show. She’s this young comedian coming up at the time. Oh my God, she was so hilarious. And then from there going to the Palace, which is this Chinese restaurant, and upstairs there was like a room that they would do stand-up in, and I saw Emily Heller at that show too. She was doing different stuff than she had done earlier that evening. I was like, “Oh, that’s what it’s like when you’re in that mode, when you’re a young comedian, and you just find your voice. The jokes are just flowing, and you just want to get on as many stages…” And I told her, I was like, “My God! The stuff you did earlier, you had all new stuff right now. That’s got to feel so great.” That made me feel like, this is awesome, comedy’s not dead.

Then I started going up a little more and a little more. What got me back on the road to being a human was not me doing sets. It was the hang. Hanging out with other comedians and watching them work on stuff and be creative and come up with angles on things that you hadn’t thought of gets you fired up and gets you happy again. Getting to have that back in my life made me hopeful again. It made me hopeful.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how Patton turned his attention outward? He got through his grief and back on stage by opening himself to other comedians, and allowing them to carry him forward.

Chapter 5: Relearning the craft

How do you find humor when you’re deep in grief? Look for the absurdity.

PATTON OSWALT: I was getting my comedy legs back. Stuff that I used to be able to recognize immediately as being great comedy fodder, because it was still so tied up with my grief and my pain, took me a few more days.

It’s hard for me to sit and write the comedy out before I do it. I jot down ideas, stuff that I want to talk about and explore, because a lot of times, ideas will come to me while I’m zipping around, I’m traveling, I’m acting in something, I’m running errands, doing daddy-daughter stuff. So you’ve got to be able to be very open about: “Can I get a pen and a piece of paper? Anyone have anything?” or just “Give me a second,” and then text something to yourself. Don’t be embarrassed about that. Grab it.

My wife died on a Thursday. I had to tell Alice on a Friday. One of the first things she said once she had stopped crying for a second was, “I want to go to school on Monday.” In other words, even if it’s fake, I want to bring some kind of normalcy to my life. I had to take her to school on Monday, and that was after a weekend of not sleeping and freaking out at the kids asking me questions. It took me a couple days after that, that I realized how absurd that was — me having to become more and more aware of what was happening around me that was absurd. And then I found a way to start talking about my grief that was funny in a way that could connect with people. And also connect with the bigger, the cosmic. Turn the mundane into the cosmic.

I had done this whole trip to Chicago at Christmas to see all of her cousins. We had blocked out all the horribleness, and I’ve given her nothing but fun and adventure and tried to keep it upbeat. Then getting to the airport, and we’re about to make a clean getaway and get back to LA, and then this woman waylays us and tells us about the horrors of losing a parent. “Oh, when I was young, my mother died. My father never got over it.” I remember at the gate, I was horrified, and then we got on the plane. We’re crying. Then it took a couple days to go, “Wait a second. That was nuts.”

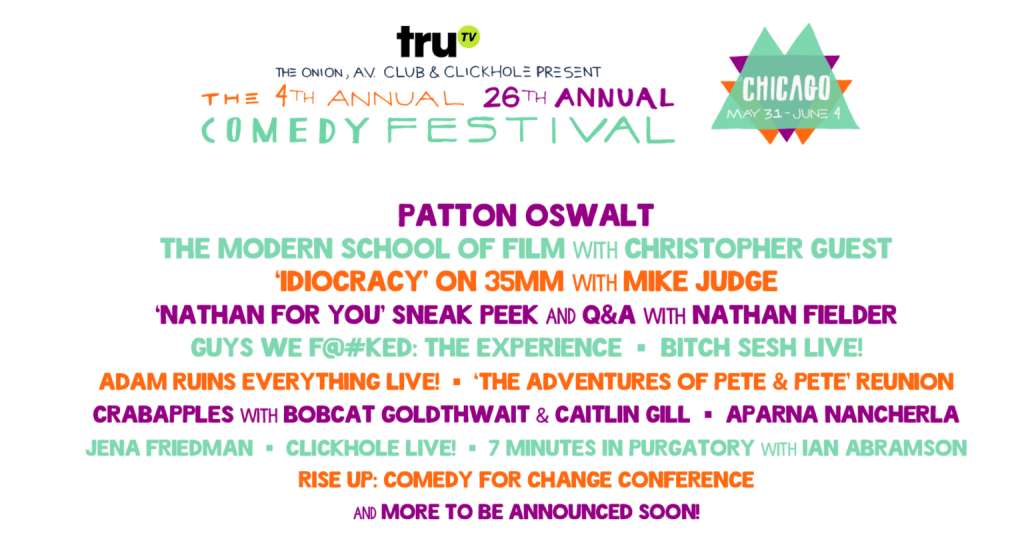

The bill for the comedy festival where Patton Oswalt taped “Annihilation.” (The playbill also features a set from the show’s director. Bobcat Goldthwait.)

Chapter 6: Taping the comedy special Annihilation

PATTON OSWALT: I had been doing shows leading up to it everywhere that I could. Show, show, show, show, show. It was so much automatic-pilot and subconscious old reflexes coming back that I wasn’t aware of because I was too aware of still trying to survive every day.

When the hour began to gel, I had this whole other level of anxiety of, “Should I even be doing this?” It felt like I was so trivializing it and making it petty by doing it as an hour of jokes.

There were a couple of times preparing for that show where I toyed with the idea where I did an hour where I never talked about my wife dying, or the fact that I had become a widow or any of that stuff, and never acknowledging that. I did it in a couple of shows that I was doing down at Irvine, and that was even weirder for the audience. It was like, “We all know what happened to you.” That option was gone. I knew that option was gone, and I had to talk about it somehow.

The day before was torture. June 1st, when I get to Chicago, I was so tense. Despite the fact that the set had been doing well on the road, there was a thing in the back of my mind of: I was going to get out there, and because of what I was talking about, it was just going to get nothing, get no laughs. Everything was: “Okay. We got to work out the camera angles and the sound check” and all this. I was just like, “Just let me get on stage and start. If I can just start, all this anxiety will go away, but can you just let me fucking start?”

Friday the 2nd of June. I’m just standing offstage with my head pointed at the ground, just trying to block out what’s happening. I don’t want to think about anything else. Have the person say my name, and let me go out.

Patton Oswalt stands backstage, about to go onstage for “Annihilation.” Image from the Netflix official trailer.

The first five minutes was terror. Just me doing jokes about life and blah, blah, blah, and talking to the audience and fun, fun, fun. I’m like, “Oh, this is going to be a huge mistake. Any second, the whole audience and me are going to go, ‘No. No, this is a bad idea. No, no, no, no, no.’” The whole thing’s going to shut down. But luckily that didn’t happen.

It wasn’t until I got to pushing through, talking about my wife passing away and then doing the bit about the Polish woman at the airport. “Oh, when I was young, my mother died. My father never got over it.”

Once I was able to acknowledge what was happening, I felt like, oh, okay.

Chapter 7: Ending a comedy show with Zen philosophy and porn

PATTON OSWALT: The last two bits in my deep searching hour about grief: one is about me pitching a movie. When you pitch movies, you reference other works. I just thought it would be so hilarious to pitch a children’s film, like a Hallmark Christmas-y film, but all of your plot and character beats, you reference the most horrific hardcore porn movies. As if everyone in the room was like, “Oh, yeah. The scene in Yank My Doodle It’s a Dandy when she pulls the train on the softball team in the hotel room. Yeah, that’ll be the same moment of decision when the kid decides to take over his father’s candy store.”

I buttoned that with her saying, like, “She would’ve laughed her ass off at that stupid bit that I just did, because she loved how absolutely dirty — and it has nothing to do about the human condition. It’s just like, we’re going to be filthy and hilarious because we’re humans. We get to do that.”

When Michelle had started off writing movies and writing TV series, ever since she heard that bit, she was like, “Whenever I would go in and pitch things, in the back of my head, I’m like, ‘I so want to just reference a porn movie right now.’” So I did that for her.

I was able to bring it back around to just this quiet thing that she said four little words, two sentences: “It’s chaos. Be kind.” It is all random. It’s as random as the set that I just did. Yes, I was talking about grief. Yes, I was talking about the world, but I’m also just talking about porno flicks and trying to make a joke out of that. That is what life is. It is that absolutely random and meaningless, and the only meaning you’re going to get out of it is by being kind to people.

The things that I think really end up piloting your life and improving you and changing you for the better are the most absolute simple things. It was Harold Ramis always going — his whole Zen philosophy was “Don’t be a dick,” and again, four words. Yes, it is flippant and funny, but there’s so much frigging truth to that.

To bring all of the complexity of my grief in that whole hour, and then one of the filthiest bits I’ve ever done, that felt like the life force reasserting itself, going, “Okay, now you got to move on.” You’re able to experience everything again, the good and the bad, but I’m going to be alive.

Chapter 8: Let’s see where it goes

How do you change artistic gears? Start with a blank page.

PATTON OSWALT: Up until that point, everything was so fraught and weighted and heavy and important.

I told my manager and everyone there in Chicago that the day after I do the special, I’m going to sleep until I wake up. Don’t book an early flight. I just need a day. I just was like, “I got that out. It’s done. You didn’t think you could do it, but you did it. Now I got to move on.” Then I went through notebooks and wrote 2017 at the top of a blank page and said, “Let me start writing new stuff now. Let’s go into it with no expectations or judgment. Let’s see what’s next.”

Patton Oswalt on the roof. This image was grabbed by the blog What I’m Watching, who writes: “Patton Oswalt looks out on the city from the roof of the Athenaeum theatre in Chicago, Illinois. This Golden Hour shot is the reward for watching all the credits, and it reminds me of the movie Birdman.”

One of the things that got me through a lot of my grief was pure absurdity, stuff like Eric Andre, and Tim and Eric, and just the dumbest shit I could find was what was reaffirming that, “Oh, yeah, that’s what you get to do when you’re alive.” I’m like, “I got into this to be a frigging goofball. When do I get to be a goofball again?”

I just started living life again, which was nice to have again. Well, now I get to just go onstage like I always do and start writing jokes, which was just, “Okay. I’m going to go onstage, and ‘hey, this thing. Let’s see where this goes,’” because it has to come out of me and sound conversational. It has to sound like it’s actually coming out of a human skull, like it’s coming to me as I do it. It was simply, “Oh, now I’m doing jokes again. Here I go.”

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how much lighter Patton’s voice got as he describes turning the page? Sometimes it’s turning an actual page in an actual notebook. Sometimes the page-turning is metaphorical. But it opens up the space for grief to give way to creativity.

Chapter 9: Let the muses find you

What do you do when an idea eludes you? Don’t beg for it. Play hard-to-get.

PATTON OSWALT: I get stuck all the time. Sometimes the hours I carve out to try to write or create something new, a big chunk of that is spent not doing anything. It’s spent staring into space and waiting for the inspiration to hit. Sometimes my strategy is to push through. Sometimes my strategy is to fake it. I put a placeholder idea there in the writing, in the screenplay, in the joke, and hope that it will fill in later, in context, if I just keep writing. Sometimes you have to play hard-to-get with these things, not be anxiously hanging out there, hat in hand, hoping that you’ll get inspired, or it will inspire you. The idea that’s in your head, if you are begging it and being needy about it coming forward, the idea won’t come forward. Sometimes you have to walk away and then let it chase after you.

So if you go, “I’m going to go for a walk. I’m going to watch a movie. I got other stuff I got to do,” then the idea will be like, “Wait a minute.” Then it will come after you. It’s, you play hard-to-get with yourself. There’s things I like to do every day, keeping the house clean and little rituals. But if I’m off doing those, the muses look at me like, “Well, he’s occupied, and we’ll go find someone else.” You have to sort of sit still, so the muses can find you because the muses are circling all over the place.

I try to meditate twice a day for 20 minutes each session, and I try my best to have a 20-minute block where I do not have any thoughts. It gives me the breathing space to be creative and to not get anxious and self-conscious of all the mundane things. “Oh, well, I’ve got to return that email. I’ve got to get some new shoes.” It’s just, “I’m showing up.”

It’s a struggle. Some days, I don’t manage to do it, but on the days that I do, I sit, and I let the muses go, “Okay, he’s not going anywhere. Let’s sit down.” I’m literally anthropomorphizing creativity, but it helps me to get to where I got to go. That’s a crude way to say it, but you got to get yourself there, and whatever way it takes to get yourself there, it’s okay.

Chapter 10: Finding the bits for I Love Everything, at Denny’s

PATTON OSWALT: It’s very easy to point out, “Well, this thing is stupid. I hate this.” But it’s way harder to go, “This thing that I thought was lame is actually kind of amazing, and I will find what’s funny in how much I love it.”

It’s my Mel Brooks theory of comedy. His best films — The Producers, 12 Chairs, Blazing Saddles, Young Frankenstein — was him looking at things that he really, really loved, but you can’t help but see the weirdest, damaged, messed-up things about them. That’s where the best comedy comes from. If you’re just pointing out that something’s stupid, well, that’s kind of easy to do, and the joke ends there. But it’s way better to go, “Here’s a thing I love, but why does this thing have all these messed-up things about it?”

Denny’s was such an easy go-to for me, too, for comedians in the ’80s, like, “Oh, we’ll go to Denny’s.” But then I was like, “But there’s something beautiful about Denny’s.”

I was there with my daughter one day, and I’m looking at these characters. They’re a little pancake and sausage, and what kid doesn’t want to have adventures with a sausage? And in a weird way they’re kind of the least friendly kid characters. There’s something in the eyes that looks kind of tired and broken and the kind of characters that truckers would like to hang out with, is a fried egg and a piece of bacon. I don’t know. There was just something so sweet.

I love the idea that Denny’s has now kind of embraced the fact that it’s a place to go to kind of sit and brood. It’s not, “Hey, upbeat family fun.” It’s not a place to be depressed, but it’s like, “The food here is solid. You’re not going to get a great meal, but you will get a good meal.” But you’re taking the question of, “Am I going to get a crappy meal?” That’s checked off, and you can sit and do the other things you need to do. That’s what Denny’s is there for, and I think it’s beautiful.

In a way, Denny’s is almost pointing the way to where America needs to go in the next 20 years. Britain used to rule the world. And it was a miserable place to live. Now they’ve fallen to three or four, and they’re a charming tourist destination for the most part. Maybe, maybe, maybe we need to fall to number two or three. Let someone else run things. We’ll still be fine. I think it’s this anxiety of having to be number one all the time that’s causing all of this despair and anger.

So Denny’s is kind of saying, “We’re not the best restaurant in the world, but we got locations everywhere, and we’re doing fine. What’s the problem? Come in and get a goddam cup of coffee. What aren’t we doing?”

That Denny’s bit was such an evolution for me when I was on the road, working on the special. That used to be in the middle of the set. It just kept getting bigger and bigger.

Then when they realized I’m ending my whole hour on, “this is the final statement I’m making, and it’s all about Denny’s,” there’s that anticipation of, “Where is he going to go with it? Is this going to be his final statement?” And that response was just fantastic to get to see.

The Grand Slams, from Denny’s, have a YouTube channel, of course.

Chapter 11: What’s funny about being happy?

What do you do if your art grew out of your pain, but then you’re blindsided by joy? You run toward it.

PATTON OSWALT: Sometimes when you’re on stage talking, a phrase will just fall together in your head and then fall out. If you leave yourself open to it, and you’re not afraid of being vulnerable, you can get in touch with some really cool stuff.

I really truly head-over-heels fell in love again, not thinking that I would. I was 49 when I got remarried, she was 47, and every marriage has problems in it, but when you’re younger, I think you look at relationship problems like, “Well, this is the end of the relationship. That’s it.” But when you get older, you get to that point where you’re like, “Yes, this is a bad fight, we’re both pissed at each other, but this isn’t fatal.”

So I’m able to talk about, in a way, way more intense things about love and relationships, but with way more of a wink and a smile to it. Like, “Come on guys, this is not the end of the world.”

Especially when you get to a certain age in life where you’re like, “Come on, you’ve been through enough shit. That’s love. You’re old enough to recognize it. Go enjoy it.”

Because I was getting loose and comfortable again on stage, and I was able to talk in those terms of “here’s how I feel,” both the positive and the negative, but able to do it honestly and with some confidence. So I was able to come up with, “yeah, when you see love, you run towards it. When you see love, you run towards it.”

Chapter 12: Taping the comedy special I Love Everything

PATTON OSWALT: I Love Everything is like a check-in and a response to the last special. I was in a dark place. I’m further away from a dark place now.

Annihilation was everybody tiptoeing around me backstage, and “leave him alone, and let him do this, and this is a very important night, and blah, blah, blah.” Feeling overly protected and kind of coddled, and like I’m this fragile, frail flower. Annihilation felt like, “Let’s see if this baby giraffe can walk for the first time.” I Love Everything felt more like the old days where friends are there. We’re all talking. I’m chatting with people literally as I’m walking up on stage. It was way looser, way more fun. It was night and day. It felt like being back in the world that I knew.

And because there wasn’t anything heavy attached to this shit, I was really able to just relax, and I even left in some moments when I was trying to do some transitions, and I start cracking up because I mess up the transition, and then I go, “I want this left in, because I’m not going to make these poor guys cut around this. Let’s just show me trying to do this.” Then that ended up getting a laugh.

I Love Everything is me just re-embracing the fact, oh, wait, I get to do comedy. I know that there’s a lot of angst about comedy right now. Comedians are suddenly acting like they hold the elixir that will cure the world, and how dare you silence me? It’s like, no, you get to do comedy. You are here to help mitigate the stress and terror of other people. You don’t need to add to their stress and terror. It’s Susie Essman going, “You’re not that important, kid.” It’s: you get to do comedy. Don’t you know how fucking lucky you are to get to do that? But it’s a reminder to me because I was getting very self-important and wrapped up in all my bullshit after Annihilation, and that was a nice little … a gentle little, “hey dude, calm down. Okay?”

Chapter 13: What I learned

PATTON OSWALT: If you are deep in grief, let yourself be deep in grief and take care of yourself first. Your creativity, your art should be a function of your life. Your life should not be a function of your art. That idea that the show must go on no matter what, I think that’s a terrible, terrible philosophy. Sometimes the show doesn’t go on because the person is wounded and needs to fix themselves. If you force yourself out there when you’re broken or you’re too vulnerable, then you’ll do work that you will hate and that you might get stuck in and that you might never recover from creatively. So go take care of your head; art will wait for you.

Chapter 14: My advice to you

PATTON OSWALT: Everyone wants to be good at something. There are a lot of accountants that actually should be ballerinas, but there are also a lot of ballerinas that should be accountants, that would be, actually, be living a happier life. And a lot of people aren’t given the chance to really, really figure out exactly what they want to do that will make them happy. And I think that’s where a lot of the pain and tragedy from life comes from, is that there are people out there that you can see how they comport themselves, and the trouble they cause is because they’re in so much pain because they are not doing what they were put here to do.

If you doubt that you have found the thing that you should be doing and like, “Oh, I should try something else,” the first thing you have got to, got to, got to get out of your head is, there is no such thing as too late in the creative arts. There is no such thing as, “Well, I’m in my 50s now, it’s too late.” It’s not. Raymond Chandler wrote his first novel when he was 51 years old, and he changed detective fiction. You don’t know. Just go out there and start. You have no idea what’s too late or what’s too early. There’s such a thing as too early, I think. Maybe you waited the right amount of time and figured out really who you are, and you’re going to do something really extraordinary. Don’t do that sunk-cost fallacy of, “Well, I put 15 years into real estate. I can’t suddenly change.” Of course you can. Of course you can. You can pivot if it’s not nourishing you. Yes, it’s paying the bills. But if it’s eating away at who you feel like you are and who you want to be, then you can’t let that happen. Just start. Start, start, start. There are people out there waiting. You just don’t know that they’re out there yet.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Patton Oswalt for sharing the story of this creative journey with us. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you found things in it you can bring into your own work.

Maybe it’s the way Patton first put himself back onstage, and found himself revived not by performing himself, but by “the hang” — and the way his fellow comedians gave him energy. Or maybe it was the way Patton gave himself — and you — permission to deal with his grief and to let the show not go on.

You might have been struck by the advice he collected from others. Like the comedian Susie Essman, when she told him: “Honey, you’re not that important.” Or the writer Stephen King, writing a little bit each day just to remind himself how to do it. And then there’s his epic advice to all of us to “Start, start, start.”