Sweat the details

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: The secret room in the attic

- Chapter 2: The first spark

- Chapter 3: Creating my first immersive performance

- Chapter 4: How I found my format

- Chapter 5: I enter a competition

- Chapter 6: I find my people

- Chapter 7: The first production of Sleep No More

- Chapter 8: From London to New York

- Chapter 9: The actors enter the building

- Chapter 10: What the audience experiences

- Chapter 11: Opening night in New York City

- Chapter 12: What Sleep No More means to me now

Transcript:

Sweat the details

Chapter 1: The secret room in the attic

FELIX BARRETT: My dad used to be a magician, and he was a magician until there was a crash. He was fine, but the tricks all got muddled, and he never did a magic trick again. And all the remnants of those tricks are in the attic.

In this attic, there was a collection of artifacts from lost years: furniture, there was probably some taxidermy, my mother’s mug collection.

There’s these magic tricks — vanishing mystery boxes where you can drop a coin in, and because of the mirrors, it evaporates.

The attic was always seeded with this absolute air of mystery. So the deeper you delve into it, the more you uncover.

A young Felix Barrett with his father, a magician. Image courtesy Punchdrunk

I remember once with my good friend, Alex Cardell from six doors down the road, we were probably about 13. We told my mom we were going to tidy the attic. She couldn’t believe it. She was like, “Oh, boys, I’m so touched.” We didn’t really mean it that way.

We took everything out of the attic, absolutely everything, installed a base, put secret passages in, and then put back the junk on top, so it looked exactly the same, as messy as it was before.

And mom was horrified when she’d come back and find the attic trashed. And she said, “But you haven’t done anything at all.” And we said, “But aha, we have. Look at this.” I peeled a cardboard box to the side and revealed a dark foreboding entrance, a labyrinth with tunnels, and dead ends, and blind corners, and a sense of threat. You could slide across bits of timber or old bits of furniture, a tabletop, and block pathways. It was almost like an impossible cipher, and you’re trying to find the secret room, which is the end goal, where my friend and I would go and have our snacks and feel pleased with ourselves for having arrived there, knowing that no younger sibling could ever find it. But we knew the way to the very heart of it.

Felix Barrett as a child. popping up from a hiding place behind the couch. Image courtesy Punchdrunk

JUNE COHEN: That’s Felix Barrett, and he’s about to tell us the story of creating Sleep No More, the immersive theater experience that’s run for more than 10 years in New York City. It’s Felix’s personal story of inventing an entirely new, experimental form of theater. But the takeaway is universal: When you focus on the tiniest details — again and again — you have the biggest impact on your audience.

As Felix takes us on the journey of developing Sleep No More, you’ll hear how he builds entire mysterious worlds by getting one finicky detail at a time just right. You’ll hear what qualities he hunts for in a new location — one that will transport an audience and cultivate a sense of magic. And you’ll learn his secret tricks for energizing a cast and crew about a new project.

And here’s what you need to know about Felix and Sleep No More. Felix is the artistic director of Punchdrunk, a British theater company that specializes in immersive storytelling. Sleep No More is Punchdrunk’s most famous and longest-running show. And let me describe it for those who haven’t been. It’s an immersive theater experience that takes place over the course of 3 hours inside a building that looks and feels like an old hotel. The performance itself is the story of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, but almost no words are spoken. It’s told entirely through movement. And it’s a non-linear telling, with the scenes from the play unfolding simultaneously all throughout the building.

When you first enter the performance space, you’re given a white plastic face mask (picture a theatrical mask, not a COVID mask). You wait briefly at a stylish bar before being led into a dark labyrinth of a building. You wander freely through rooms with antiquated decor. You may stumble into the bathroom, with Lady Macbeth lounging in a bathtub. And all the time you’re surrounded by the actors and by other mask-wearing guests.

“SNM,” by Michael Banani, on Flickr.

Sleep No More was first produced in 2003 in London. It was then remounted in Boston in 2009. In 2011, the show arrived in New York City, where it became a hit, and as of 2022, continues today after a 2-year pandemic break.

[THEME MUSIC]

Chapter 2: The first spark

FELIX BARRETT: I was 15. It was probably a Wednesday. In the morning we had a class with an absolutely inspirational teacher. He was teaching us about atmosphere. We read some texts from The Cherry Orchard, the Chekhov play, in our classroom with the lights on. As you’d imagine, everyone’s bored, tired, dreary. He said, “Okay. So that’s one way of interpreting the text. We’re going to do it again.” Then he made us switch all the lights off. We went underneath the table, and we lit a candle, and we read the same text by candlelight. And suddenly it’s hushed. It’s gentle. It’s secretive. It was whispered. And the torrent of atmosphere washed over us. He said, “Right, with that in mind, now we’re going to go and see this work by Robert Wilson.”

Incredible American director Robert Wilson. Around the mid-’90s he created a piece called H.G., based on H.G. Wells, in the Clink prison underneath London Bridge. It blew my mind. I’d never to this point seen anything like it. It was the most sparse design. It was almost 90% darkness, an astonishing atmosphere. It was essentially just an art installation shrouded with infinite obsidian gloom. It was the first time I realized: Wow, this could be considered art. It wasn’t a painting that you see in a gallery, it was something that made you feel something, was an artwork. There probably wasn’t anyone there. It was probably just us and the magic of being in a vast space, but being alone is very precious.

An excerpt from a film about H.G., by Robert Wilson & Hans Peter Kuhn. Filmmaker Mike Figgis captured these images from the subterranean Clink Prison.

The class came out, but I was missing. My schoolteacher, he had to go back in and find me. I was just lost in the moment in absolute admiration of this creation.

The next weekend, I said, “I have to take my family,” took them, but by this point, its magnificence had caught on around London. There were queues around the block. And when we got in, what had been this empty sort of barren wasteland was suddenly full of audience. And I was so cross with all of them. Like, how dare they come in and spoil the atmosphere? I thought, how can you create work that is thick with atmosphere, but will remove the audience from the picture?

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how different Felix’s story felt the moment his school teacher had them read by candlelight?

That one detail transformed the entire reading for young Felix. And that technique — of finding the tiny detail that has the biggest impact on the experience — that’s the formula you’ll hear him come back to over and over.

Chapter 3: Creating my first immersive performance

FELIX BARRETT: I went to every single hairdresser in Exeter and asked to collect their hair cuttings. There’s a scene where a lowly paid soldier is cutting the hair of his senior officer. So I had a mountain of human hair for that final module of my drama degree where you took over a site that wasn’t a theater space; you direct in found space.

The rule set of conventional theater: picking up your tickets, going to your chair, sitting down, the lights coming down — that creates a veil of safety, which in turn switches off most of your brain activity. If you change that rule set so an audience doesn’t quite understand how to engage with it, suddenly you’re switching on all of that brain power, and they’re physically active. Every single individual will have their own moments of, like, “Oh, I got it. I found this. I did that.”

Did a production of Woyzeck, found a disused territorial army barracks, incredible space. Nature had totally reclaimed it, and ivy had encapsulated the entire building. Lit it with candles, because I had no money. Borrowed a snare drum from the music department. And I had fireworks that make big bangs to create sonic moments, just to destabilize the audience.

The idea of theatrical danger, an audience not knowing if it was safe or not. How can you protect them so that it’s a safe space to be frightened? They’re flooded with adrenaline. To then story-tell — whether they enjoy it or not, you certainly feel alive.

I scattered the play across the building, letting them explore. The audience cohabited the space with the performers.

But there was one thing that was bugging me: How would you know who was the audience and who were the performers?

I didn’t know what to do. It wasn’t going to work. I remember being in bed on a weekday morning and having a genuine eureka moment, “Oh, my gosh. We put the audience in masks.”

Mask-wearing has always been about witnessing it on the stage. It’s a device to actually enable actors to be more expressive. But if you have an audience who are exploring, why not let them become characters? Take the masks off the stage, giving them to the audience. That’ll make the show work.

So I quickly went and got some masks. I pressed them myself in the art block of university, cut out the eye holes and everything myself, and then a few days later did the show.

My mom, again, bless her, came after the show and said, “Oh, Felix I’m so, so sorry. I’ve really ruined it for you. I don’t know what came over me. I had the mask on, and I ended up sitting on the knee of a performer. I behaved like it wasn’t me.”

I hadn’t anticipated the extent to which it would be transformative and empowering for an audience. It enabled a sort of freedom and allowed them to be more adventurous and break free of their adult shell.

And I thought that was going to be it. That I was going to move on to something else. And it literally wasn’t until one of my classmates said, “Wow, there’s something in this. You should do one of these again.” And that’s the first point I thought, “Oh, maybe I should.”

Chapter 4: How I found my format

FELIX BARRETT: We were such a tiny little thing, totally fringe. We did all manner of projects for no money at all. None of us got paid. The form was almost right, I could tell there was something there, but it just didn’t deliver.

We did The Tempest. So you’d explore this incredible old warehouse. This cavernous, moist, desolate building. You’d take 20 minutes to navigate it. You’d finally see Prospero in the distance, the famous old wizard. And then he would just do a monologue. And it was absolutely underwhelming. You’re so pumped, and then it’s anticlimactic to get some text.

So if I could remove the language, so it didn’t matter what your native tongue was, but you can understand someone’s physicality, that’s universal. And suddenly it would soar.

I heard along the grapevine of a show that was happening outside of a theatrical space by a dance company.

So I rang up and said, “Oh, my gosh, are you doing a site-based show?” And they’re like, “Yes, we are.” And I said, “Oh, can I come and see it?” The lady, who was very nice, said, “I can’t get you in. We’re totally sold out.” So I never saw the show. She said, “But, if you’re interested, and you make this sort of work, we’re running a competition. Why don’t you submit an idea?”

Chapter 5: I enter a competition

FELIX BARRETT: She said, “The deadline’s in three days.” So in my frenzy, I said, “Film noir, well, Macbeth has got a film noir protagonist. You got the femme fatale as Lady Macbeth, and it’s a dance company.” So in a spontaneous moment, I just said, “We’ll do Macbeth as a film noir thriller, and we’ll transpose all of Shakespeare’s language into a gestural, contemporary dance language. Not a word will be spoken. It will all be physicalized.”

At that point, I never even met a choreographer. The language of choreography and contemporary dance, I didn’t speak it at all. I knew nothing about it.

So the proposal, they just wanted an email. How do I make them hear my idea? And how do I convey the atmosphere I wanted to bring.

I had a suitcase. The suitcase was from that same attic that I spoke about earlier, amazing ochre tan leather falling to bits, a broken clasp, like a forgotten object, but inherently magical because it’s so antiquated.

So rather than just submit it on email, I typed it out on my old typewriter with all the terrible spellings that you would imagine, folded it, put it in an old envelope, put it in one of my old grandfather’s dusty breast pockets of a suit. Put that suit, old pair of shoes, tie, whiskey bottle, put it in the suitcase. And I delivered the suitcase by hand to their office.

There’s a lapse of a couple of days where I was thinking, Was that an idiotic thing to do? Should I have just emailed it like everyone else? Thinking, Oh, why did you take it too far? And I get a phone call, and they say, “You’ve won. We are going to produce this show for you.”

The suitcase in which Felix submitted the original pitch for what became “Sleep No More.” Image courtesy Punchdrunk

JUNE COHEN: As Felix described his winning proposal, did you find yourself imagining what it would be like to receive it? Turning from your computer, unbuckling the worn, leather suitcase to reveal a folded suit with the proposal in the pocket.

It’s Felix’s attention to detail — even in his pitch — that made all the difference. If he’d sent the same proposal through email — as he’d been instructed — he may never have found the people who propelled him on the next phase of his journey.

Chapter 6: I find my people

How do you break through as a newcomer? Find a like-minded sparring partner.

FELIX BARRETT: I’d found my people. I suppose it was what I’ve been craving. It’s like, you want to meet like-minded individuals who share the same vision, and you can share a language, and you can develop a shorthand.

We had a shared view on the world and a belief that together, we could create something that was greater than the sum of its parts.

Colin Marsh, who was our first executive producer, applied for some substantial money for us. It suddenly professionalized what I was doing, enabled us to pay the performers and things that I couldn’t have imagined possible before.

I said in my proposal, “here’s the show,” but I said, “I need to be paired with a choreographer.”

Colin said, “I know just the perfect person for your choreographer.”

He introduced me to Maxine Doyle. And I remember that first meeting with her. The meeting was in a cafe in a part of London that I hadn’t been to for a long time. It was so alien that I almost had that sense of out of body, of being a stranger in my own town. She’s a bit older and was more experienced and more of a track record. I was just this young newcomer. When she turned up, looked me up and down, she said something like, “Colin says you’ve got an interesting idea. What is it?” And I felt like I had to sort of pitch it to her.

She got it immediately. And what was incredible was that most of our instincts are the same. Even though she came from a different performative form, we had a common vocabulary and that was really exciting.

It was almost 20 years later. You don’t realize at the time how seismic those meetings are when you meet someone who will change the face of your life, and who are the yin to your yang. Maxine Doyle, now my almost 20-year-long creative sparring partner and the co-director and co-creator of Sleep No More.

Chapter 7: The first production of Sleep No More

FELIX BARRETT: It was around Christmas. Found an old Victorian boys’ school in South London, and I think it’d been closed for at least 20 years. It was a derelict building, it had no heating. So we were all in full winter gear, full scarves. The poor performers with their ‘30s slips, but actually, goose-pimpled and shivering.

We only auditioned 16 people, and 10 of them were in the show. With our design budget, maybe 3,000 pounds, like $4,000. It was tiny. And at the time it felt huge. We probably spent most of it, if not all of it, on trees, which were real trees. We’ve got a real forestry department to cut them down, and we filled the entirety of this space. So the smell was absolutely thick and pungent with snowy pine. It was utterly intoxicating.

It was very, very, very dark. I was doing the lighting; I’d bought a lot of the cheapest fairy lights, Christmas decorations. And I think we only had four lights, and I was operating them on a slider up and down.

So when I wrote the idea right down on the piece of paper in the suitcase, I loved it so much. On that opening night, it was the absolute opposite. I actually kind of hated the show. I was so embarrassed that people were coming to see it; it felt like we failed. It could have been so good. I doubted so much that I avoided everyone, and I hid amongst the pine trees in the forest.

I’d operated the lighting, and I didn’t go into the bar afterwards to see everyone. I can’t bear to see people because we haven’t got it perfect. And it was only the next day when people said, “Hey, it was okay. People didn’t hate it.”

It was the first time that the form clicked together. We had an audience that came back time and time again.

Rather than doing a run of one or two nights, we were doing two weeks. On the last night, a hundred people came to see it and we couldn’t believe so many people wanted to come. It blew our minds.

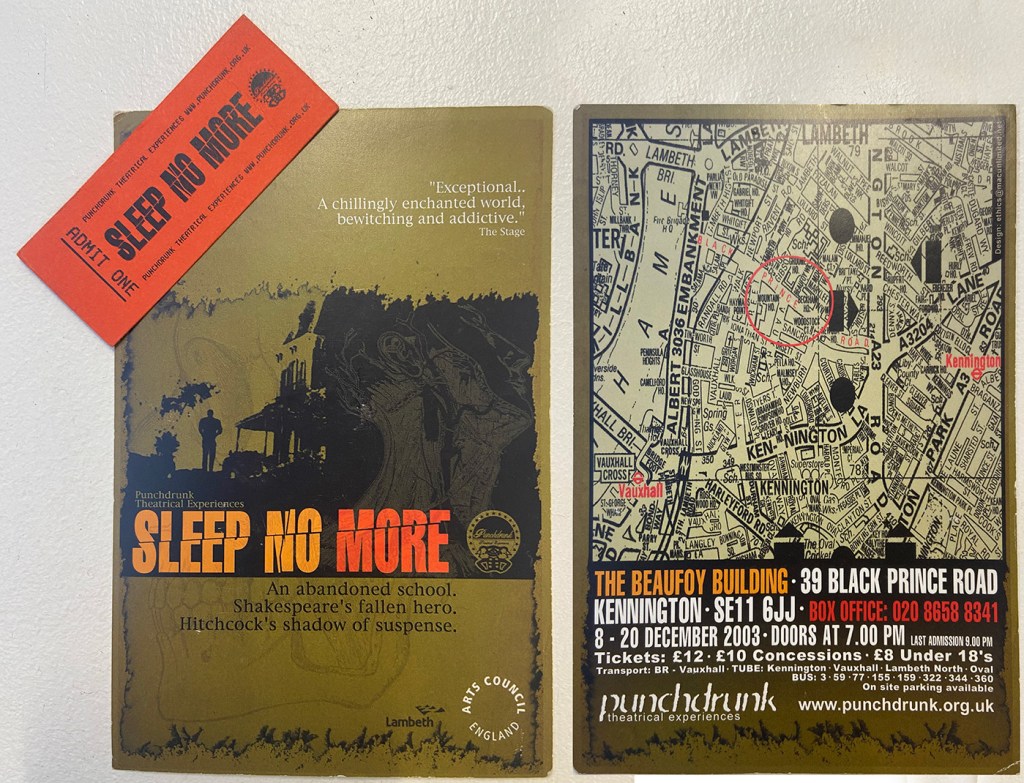

“An abandoned school. Shakespeare’s fallen hero. Hitchcock’s shadow of suspense.” Ticket and publicity material from the first production of Sleep No More, on Black Prince Street in London. Image courtesy Punchdrunk

Chapter 8: From London to New York

How do you read the emotional blueprint of a space? Listen to every creak, crackle, and whisper.

FELIX BARRETT: You can only experience things truthfully once, because the second time you experience something, you have a set of preconceptions, and you’ve already got the baggage of the first time.

7, 8, 9 shows in London. We got an audience who were coming back and knew what to do.

I really wanted to go to a new city where people had never seen it before. And I knew I wanted to get it to New York because it’s the theater capital of the world.

We started talking to producers. We were introduced to Randy Weiner. We’re looking at buildings in Sunset Park and all over deepest, darkest Brooklyn. I love being off the beaten track because you want an audience to have to work hard to discover it. If it’s too easy, they won’t appreciate it.

I was a bit skeptical about Manhattan. I was like, “You sure? I feel it’s a bit too central.” Randy made us get off at a certain subway station. The whole street was derelict, and he walked me around the longest way possible. So I thought I was going further, really to the middle of nowhere. And actually it was super accessible, very smart.

It was multiple warehouses knocked together. It had had so many different uses that it had almost forgotten its identity. Most recently it had been Club Bed, like a rooftop bar that you got tucked up into bed, and someone brought you a cocktail. But then there’d been an altercation on the top floor, someone had been pushed against the doors of the elevator, and they’d opened, and someone had sadly lost their lives. So when we got there, there was still police tape because it was literally a crime scene. I was like, “Well, this is just perfect for Macbeth.” The literal ghosts of the past are in there.

This video from coolhunting.com explores the built environment of the McKittrick Hotel.

If you were to come on that first walk around a building, I would be listening to every single creak and crackle and whisper of the space, following my nose and letting the architectural, emotional blueprint of that environment lead me around. And I log: where’s the safest room in the building, and where’s the most threatening?

The ballroom, because it had been used to be a nightclub, had that sense of euphoria and shared experience. It felt safe. The top floors close to this incident were thick with threat. There’s one door we actually had to nail shut. It was quite intimidating.

You could feel the specters of its past stories haunting it. The space was so thick and pregnant with presence.

It wasn’t even a very long tour, maybe like an hour and a half. And I remember saying to Randy, “Yeah, it’s absolutely perfect.”

Chapter 9: The actors enter the building

How do you connect your team to a new space? Create an indelible memory that they can draw on.

FELIX BARRETT: The first time the cast are allowed to see the building, we play a game of hide-and-seek. Myself and the team lay out tasks in every single room, and then the cast go in one by one.

One task that has been in every single hide-and-seek ever since my finals, 20 years ago, is: Tell a fairy tale to the little boy in the corner. Be very careful, as he’s quite distressed. But it’s just an empty room.

Some people can spend half an hour in that room. Talk this imaginary child down, calm him, calm him, calm him and wait till he’s asleep and then leave. Others will be quick in and out. They’ll describe, they leave, and they can hear his cries.

Other things are practical, like: Count back down from 10 and turn around. Others are physical, like: Be still, listen to the sound of the space, and try and build a solo to it.

It’s all to create a set of memories that can be utilized, so that there’s a real emotional connection to this room. Ultimately it’s hide-and-seek. It’s a playful thing, so they get that childlike sense of exploration that we as adults have drummed out of us. It’s sad that actually you can’t be completely carefree because you have responsibilities. If you can remove that, and for a few hours let them just be completely instinctual, really surprising discoveries are made.

It lasted maybe 4 or 5 hours. They just got lost in the world of it. And what’s so incredible is just to listen to their tales told back to you at the end of that session. We shut the building down, and they tell the story of what happened. The adventures they had, the things they saw, indelible prints they left on the walls, memories they made. They end up spooking themselves. The building haunts them, so they’ve got such an incredible toolkit of emotional responses from which to then build the show on top of.

I wanted to enable the cast to experience it as themselves, but also through the lens of the play and through the lens of the feelings that we’re going to want to imbue in the audience.

JUNE COHEN: As Felix describes this game of hide-and-seek, did you imagine yourself discovering each corner of the building — as if for the first time? Did you see that frightened boy in the corner in your mind’s eye?

Felix’s belief in the power of first impressions is what drives his approach to theater-making. His observation about how a first experience imprints on each performer — and therefore on each performance, and each audience member — is another example of how tiny details matter, not just in the final product, but in the process that brings it to life. And it’s a ritual you can adapt to any team in any field.

Chapter 10: What the audience experiences

FELIX BARRETT: When audience members arrive, they’re stumbling across a forgotten grandam of the McKittrick Hotel, in its heyday in the ’30s. It’s like a segue from normal New York life of cocktails and meeting friends and loved ones into someone else’s dream.

The audience enters in small waves, sometimes by themselves, sometimes small groups. And then once they’re inside the hotel, they can go anywhere they want, and any floor, explore anything. It’s a gradual descent into the maelstrom. Forgotten hotel bar and then into a hotel elevator. Receive your mask and be pulled into the fever dream of the play.

Inside the hotel, the story of Macbeth is taking place. Every single scene is happening but in real time and across every single floor simultaneously, as though it were real life. But it’s all transposed to a contemporary dance language, so it’s all gestural, but every single beat of the play is there.

You need to experience it alone. No two audience members will have the same experience unless they’re literally holding hands. And if they are holding hands, we will find a way to separate the two of you.

The audience get to choose which characters they follow, which order, which route, whether they stick with one, whether they hop around.

There’s no right or wrong way to do it. Anything that takes your fancy, whether it’s the performer whose story you want to find, whether it’s the music that leads you around a corridor, whether it’s the detail of a letter that’s been dropped on the floor underneath a table, whether it be led by the architecture of the space or by the narrative.

You might well discover Macbeth quite early on. You might not find Macbeth for half an hour, but that’s totally fine. If you’d follow him suddenly you will get a linear version of the story, but it’s almost as though you, as audience, are voyeurs; you are witnesses to the action. But you’re also almost like a floating Steadicam watching the action in real time, watching a living movie.

The building swells, ebbs and flows, as big scenes pull everyone together for parties or for banquets. That also dissipates. For an audience to navigate the space and choose whether to ride on the coattails of a witch or to follow Lady Macbeth as she descends into madness, the choice is theirs.

Chapter 11: Opening night in New York City

FELIX BARRETT: There are so many things that go wrong. There’s never enough time to rehearse these things with a live audience. Because there’s no backstage, there’s no green room, the cast are on display for 3 hours, and it’s absolute scrutiny. The tiniest error will be picked up. In previews, cast members go to the wrong floor. The audience are all there, there’s no scene, or someone would come in for a moment of a key narrative hook, but there’s no one to perform to. So they have to, they really do have to improvise.

I was so nervous that — very similar to London where I wasn’t in the building — this time we’d scaled to a place where I was no longer operating the lighting. I went over the road to our neighborhood pizzeria.

It was the most weird thing, knowing that it was happening inside over the road. But I was terrified to see. And I waited until after the show had come down and tentatively walked back in, and I asked the stage manager, “How’d it go?” And she said, “It was great.” And the sense of relief, of just like, “Ohhh.”

It was incredible, the New York audience, because there was such an excitement. The British are quite reserved and would politely stand back and watch a scene. Whereas the New York audience were glorious, and they just wanted to get in as close as they could, knowing that they could go through the set and actually rifle through the drawers and everything. And it was ransacked. And ever since then, we actually need to bring in a team to restore and fix things. It was New York exuberance, and we loved it.

It had taken such a long time to get to New York. The show had evolved so much from the kernel of an idea that was in London, to the full stature, full bells and whistles, extra characters, extra design, extra budget, to have finally achieved the endpoint of that sense of a journey having been completed. That adventure was incredible, and we celebrated into the night.

Chapter 12: What Sleep No More means to me now

FELIX BARRETT: Sleep No More, now, is just … it feels a bit like a love letter to New York. It gave me that relationship with the city, and it’s also been a throughline to my career, being young and trying to break a new form through to the first long-running show we’ve ever had. So I feel I owe everything to it. We only put it on sale for 6 weeks. So, from six weeks to 10 years is astonishing.

We feel we need to keep it fresh for audiences and for ourselves, so that we are inspired by it, so that it still has the residual danger, by the meticulous rehearsing and the attention to details, so that you can’t be slapdash. You can’t say, “oh, it’s loosely this.” It’s like a sharpened diamond.

There are probably about 16 secret locked moments behind hidden doors that you can only access if a performer’s eyes alight on you, and they unlock it for you. And some of those have changed over the years, so that you never quite know what you’re going to get and what that secret might be. It keeps the tension up, and it keeps everyone on their toes, and it keeps it fresh. And no matter how many times people have been, I’d wager there’s a room they haven’t been in. Every time, you see something new.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Felix Barrett for sharing the story of this creative journey with us. And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you found things in it you can bring into your own work.

Maybe what will stay with you is that story of Felix reading Chekhov under a table, by candlelight. The small, impactful detail that started it all. Maybe it was Felix’s first proposal for Sleep No More — submitted by suitcase, instead of email — or his “eureka moment” when he realized that each audience member could be transformed through the single detail of wearing a mask.

Maybe it was all the intricate details in the set of Sleep No More, or the game of hide and seek he had each cast member play in the space. But each of these story details add up to one big takeaway: To create something larger than life, you have to pay attention to the tiny details; you have to sweat the small stuff.

About the Creator and Host