The best person for the project

How do you create an authentic character? Start with your authentic self. When Kemp Powers joined the writers’ room at Pixar, he found a story waiting to be told … anchored within his own story. Spark & Fire follows Kemp on his own hero’s journey of co-writing and co-directing Soul, Pixar’s first film with a Black protagonist, from his first trip to the Pixar campus to his development of the main character – and his passionate pitch for the beloved barbershop scene that nearly got cut from the film. Hear Kemp tell the story in his own frank and funny words, with creative insights for anyone trying to choose the projects that will matter most.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: The best person to tell the story

- Chapter 2: I get the call

- Chapter 3: The scene in the barber shop

- Chapter 4: Writing is different at Pixar

- Chapter 5: The setback

- Chapter 6: This is actually my second try

- Chapter 7: Going where no one’s gone before

- Chapter 8: When it’s all spliced together

- Chapter 9: The First Screening

- Chapter 10: The stories I want to tell now

Transcript:

The best person for the project

A Soul brain trust meeting at Pixar, with director Pete Docter, co-director Kemp Powers, animator Trevor Jimenez and writer Mike Jones. They met at Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, Calif, in July 2019. Photo by Deborah Coleman / Pixar.

Chapter 1: The best person to tell the story

KEMP POWERS: The main character was a Black man who seemed to be middle-aged, and the journey that he was trying to go on felt very familiar to me. Someone who’s relatively content in their job, but they’ve been pursuing some other passion on nights and weekends, most of their lives. You finally get to this point in your life where people around you are telling you it’s time to give up on that dream and settle into what you know you can do and be happy with that. That’s kind of the crossroads at which this character was in the beginning of the movie, and I related to that.

If a story doesn’t speak to me on a personal level, then honestly, I’m wasting the time of the people who want to hire me, because I don’t believe the most talented person is the best person to tell every story. I think the person who has the most passion for that story might be the best person to tell the story

JUNE COHEN: That’s Kemp Powers, and he’s about to tell us the story of co-writing and co-directing the Pixar film, Soul, which won both the Oscar and Golden Globe for best animated film.

It’s a specific story about a writer bringing a character to life. But it’s also a universal story about holding out for the creative work that’s uniquely right for you. And for bringing authentic details from your own life into your work.

As Kemp takes us on his creative journey into Pixar, you’ll hear how you create your best work when you’re the best person for the project.

And here’s what you need to know about Kemp Powers. He spent 17 years as a journalist before making the leap to theater and film. And in 2021, he captured two Oscar nominations — one for Soul, and the other for One Night in Miami, a screenplay he adopted from the play he wrote.

For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com/soul.

[Theme music]

In this carefully observed scene from Soul, Dez the barber is cutting Joe Gardner’s hair in a Queens barbershop full of memorabilia. “The barber sequence might be one of the two or three most reworked and rewritten scenes in the entire film,” Kemp says. “I rewrote it so, so many times.” At the far right of this image, barely within the frame, is a poster with great meaning for Kemp – read on as to why. Image courtesy Disney/Pixar

Chapter 2: I get the call

What do you do when the wrong project comes knocking? Wait for the right one.

KEMP POWERS: I tend to really listen to people who I respect, and they’ve always told me about the power of saying no. You’re afraid that when you say no to things that no opportunity is going to come up again, and I just haven’t been.. I just feel…. So I tended to say no a lot.

When Pixar first called me, I was kind of having one of those moments where I wondered if I’d just made a huge mistake. There was an offer that was put out to me, to work on a television show, and I declined it.

I’d look at the stuff and go, “That’s really interesting, but I’m not the guy.”

My manager was just … livid might be a stretch, but he was baffled about why I would say no to guaranteed money, considering I had nothing else going on. So I was having one of those moments where it was like, “Oh, man, Maybe I should’ve listened to him. And then I got a call.

I asked what was the project, for details about it, and my agent knew nothing. Apparently he was like, “Pixar are so cloak and dagger that they won’t even tell me what the project is.

A car with a driver came and picked me up from my home here in Los Angeles, took me to the airport at LAX. I flew up to Oakland, where there was another driver waiting for me. That driver took me to the Pixar campus in Emeryville.

They just marched me into a screening room and screened what was a very early rough version of what would become the movie Soul. What I saw that day, it wasn’t a Pixar movie yet. It was missing a lot of stuff. But I also saw the incredible potential.

I was like, “Oh man.” I feel like I could really help make this into something special.

Pete Docter and Dana Murray, the director and producer came out, and I gave my honest notes.

Within just a few weeks, I was trying to find a place to live in Emeryville and commute between cities for a couple of years.

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice the way Kemp’s manager had a hard time understanding why Kemp would turn down a project, when he wasn’t so busy? That’s a reaction you can expect to hear, if you take Kemp’s advice of holding out for the projects where you’re truly the best person. But it pays off. And that’s the theme you’ll hear throughout his story.

From left, co-director Kemp Powers talks with director Pete Docter and producer Dana Murray in early March 2020 in a room filled with planning calendars at Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, Calif. Photo by Deborah Coleman / Pixar

Chapter 3: The scene in the barber shop

How do you bring an authentic story to life? Start with your authentic self.

KEMP POWERS: When I started on the film, despite the main character being Black, the only Black characters I saw in the reel were him and his mother. So I had questions about, “Does this guy have any friends? Does he have any kind of relationships at all? Is he the world’s loneliest man?”

One of the big questions that I had was, when is this film supposed to take place? We were having these discussions, and it felt to me maybe this took place in the 1970s or something like that. A lot of that came from a lack of specificity around the character of Joe. But once I found out that it was supposed to be modern and that Joe was exactly my age, I could fill in a lot of the blanks. Things that he would know, the places he might go, the nature of some of his relationships with friends. And I was able to really mine my own life experiences.

To give you a great example, this was in the reels when I saw them. There’s a point in the story where Joe has this opportunity to play the gig of his life, but he has to get ready, and that involves getting a new suit. And one of the first things I brought up was like, “and he also needs a haircut.” And Pete’s like, “What do you mean?” I was like, “No, you don’t understand. That haircut is as important to Joe as the suit.” There was a bit of debate. It’s like, “Well, a haircut’s not as important as a suit.” And I said, “If I couldn’t fit in a haircut with my barber, I wouldn’t have flown up to Pixar for the interview.”

That’s how important … if Joe cares about presentation and in the character’s design, his hair was just kind of bushy. I was like, “There’s no way he’s going to waste his time getting an incredible new suit and not fix that hair. Get it lined up, whatever. That became the genesis of a sequence that took place in the barbershop.

The scene begins with the sound of the clippers and Black hair falling gently down to the floor. That was the first thing I wrote. And no matter how many times I rewrote that scene that stayed.

It was a scene that was populated with all Black people, which really excited me.

The scene has to be dressed. So the question comes up, what’s on the walls? Because Joe lives in Queens and the barber would be Queens-centric. The music albums that were on the wall and making sure that it was just Queens rap artists. It was like a Queens only wall.

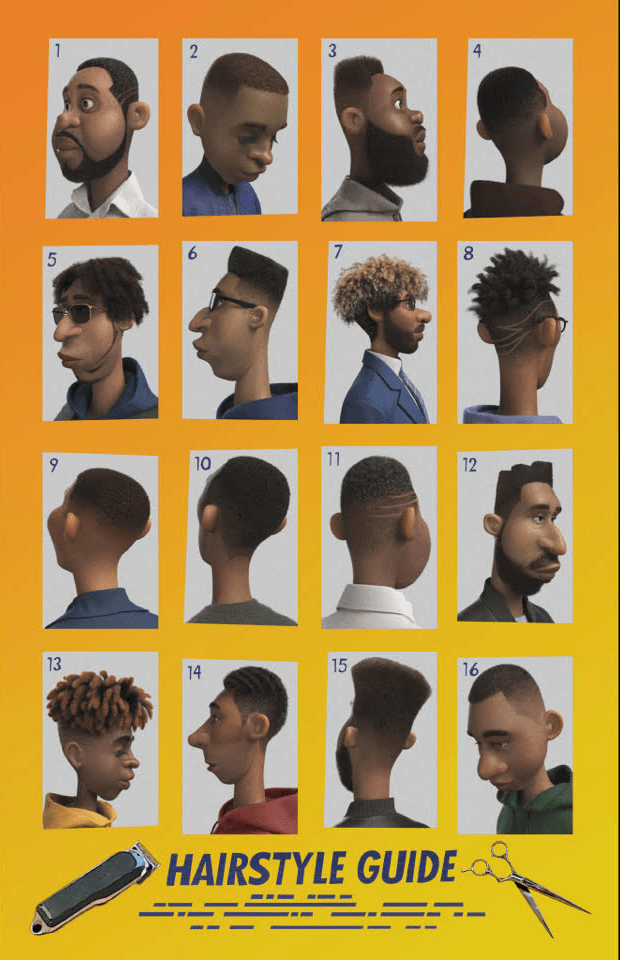

Every barbershop has these Black men’s hairstyle posters, and it’s got 16 or 20 different photos of Black men with their various Black hairstyles. The production folks were like, “Okay, great. So what should the hairstyles be?” And I remember how fun it was to write up a list of all these different Black men’s haircuts. In many cases, even I had to think or ask friends what certain styles were called. And then just made a long list of them, waves, fade with lines, twist curls with fade, flat top with stairsteps, blow out Afro, tapered fro, frohawk.

It’s a detail that you’ll see for less than a second on the screen.

But the production folks went and created each one of those hairstyles on the head of a character and created this very authentic looking Black men’s hairstyle poster. And I loved it so much that I got that poster and I blew it up and framed it and put it on the wall in my house.

JUNE COHEN: Could you hear the smile in Kemp’s voice when he described the haircuts in the poster? That’s the sound of someone whose passion makes them the best person for the project. And from the haircut poster in the barbershop to the fact the barbershop scene existed at all – it’s so clear the way Kemp brought his authentic life into the project, for the betterment of both. And the question for you is: What lights you up that way?

Kemp Powers: “I remember how fun it was to write up a list of all these different Black men’s haircuts: waves, fade with lines, twist curls with fade, flattop with stairsteps, blowout Afro, tapered fro, frohawk. It’s a detail that you’ll see for less than a second on the screen.” “Hairstyle Guide” poster from Soul. Courtesy Disney/Pixar

Chapter 4: Writing is different at Pixar

How do you make creativity a team sport? You learn to play your position.

KEMP POWERS: Screenwriting is usually a solitary pursuit. You write a treatment. That treatment becomes an outline or a beat sheet. Once that beat sheet is approved, you go away for 12 weeks or so, and you come back with a script. That is not what we do. That is not what we do at all.

Writing is something that happens almost every day and it’s happening even as the film is in animation. You’re just writing and writing and writing. You’re sitting in the edit and you have your laptop because you make a discovery and edit and very quickly rewrite lines based on what you’re seeing. And you quickly get a scratch voice actor to go into a booth, re-record those lines and then we throw it up and edit a few hours later.

Soul would be broken down into what we call sequences. The closest equivalence is a scene. I might be writing in the second sequence, the 10th sequence, the 17th, and the 35th at the same time. And so your brain is constantly trying to remember what came before and what comes after the thing that you’re working on. And hoping that when you plug in this new thing, it fits.

Ideas can come from anywhere, honestly, anyone on the team. It’s really a group sport. It’s the ultimate form of collaboration, but as the writer, it’s your responsibility to process those ideas and actually write the script.

Each scene, or sequence, is storyboarded by a concept artist (this sequence comes from artist Tony Rosenast). But the process of pulling the film together does not end there. Kemp finds himself “writing and writing and writing” as the story begins to coalesce. Courtesy Disney/Pixar.

Chapter 5: The setback

How can you turn criticism into creative inspiration? Look for the note behind the note.

KEMP POWERS: The barber sequence might be one of the two or three most reworked and rewritten scenes in the entire film. I rewrote it so, so, many times. It was easy to make it incredibly entertaining. It was easy to make it really, really culturally specific, but then there would just be more and more questions about whether it belonged there.

I really was committed to like, “Oh man, this guy, he needs to pass through authentically Black spaces,” as I call them. And there’s no more authentically Black space in the black community than the barbershop. It was really important that we try to represent that in the film. It was important to me.

We had to figure it out.

People would say that they weren’t sure why, but the barber scene felt like a double beat. It felt like what we were learning about Joe or what Joe was learning about himself in that moment, it felt like he should know that already. This scene has to accomplish those goals better than anywhere else in the entire film.

There’s this expression called the note behind the note. Sometimes people will give you a note and the note doesn’t really make sense. they aren’t able to articulate specifically what the problem is. The fact that it’s bumping for them means that there’s something that needs to be addressed, so it’s up to you to find the note behind the note that they’re giving you.

That made us have to go back through and look at earlier parts of the film.

There was a scene earlier in the film, Joe had a downstairs neighbor, Natalia, she spoke almost no English whatsoever. But Joe had a bit of a relationship with her.

They realized that in Natalia’s early days she was actually a circus performer and that she trained bears with her husband. It was this really sweet reveal that this little old lady had this whole glorious life that Joe knew nothing about. That was the source of the double beat note. The barbershop was replicating a different version of that beat – that ultimately ended up being cut.

The thing about the Natalia beat that seemed to not be as strong as the Dez, the Barber beat was that Joe would’ve never called Natalia his friend.

The thing about a barbershop is often the relationship you have with your barber is going to be the longest relationship you have with anyone in your life, other than your wife or children, sometimes longer than either. I figured here’s a guy who would know the main character. In fact, here’s a guy who might know things about the main character that the main character doesn’t know about himself.

He had never so much as asked his supposed friend a single thing about his personal life in probably 15 years. To me, that was a way more profound discovery for Joe to make, and it would spark a greater turn in Joe as a character.

JUNE COHEN: If you’ve ever received feedback on your work that mystified you – you can probably relate to Kemp’s journey here. And also: put his tools to work. This idea – of looking for the “note behind the note” – is powerful. Because when you’re truly the best person for a project, you’re also the best person to interpret feedback – and find the kernel that rings true for you.

After the break, Kemp shares the bit of Pixar magic that made his jaw drop….

Chapter 6: This is actually my second try

How can you get back in the game after a failure? Remember what you’ve learned, then take a leap of faith.

KEMP POWERS: It was in 2002, I got awarded a Knight Fellowship in journalism at University of Michigan. It gave me an opportunity to take a sabbatical year off.

I wanted to take creative non-fiction, and the only one available was screenwriting. At the end of the semester, the professor, he said, “you did a really good job.” Apparently he got like 14 romcoms and then my dark, brooding drama. He was like, “It was just refreshing to see something different.” He said, “You show some real promise in doing this. You should pursue it.”

So I quit my journalism job and decided to just throw my hat into screenwriting. I was still in my twenties. I was like, “I can write anything.”

I can’t tell you how demoralizing it was. I would write these spec scripts and someone would say, “Oh, man, that script you wrote was one of the best things I’d ever read. It’ll never get produced.” So after a few years of doing this, I had this moment where I just said, “I don’t want to do this anymore.” So I went back to a full-time journalism career for the next decade. I thought that that was my brush with Hollywood, beginning, middle, end, over.

A decade has gone by, I was closing in on my 40th birthday, well past what should have been my sell-by date by most people’s guesstimations. I don’t want to say I was dragged kicking and screaming back into Hollywood, but it was close to dragged kicking and screaming. So it seemed like an absurd thing to go take a leap of faith on.

I don’t have as much leeway to make bad decisions as someone who’s 22 years old. It’s like I can’t write crappy scripts for 10 years and work on projects that I just, I’m not interested in or just to get a check because I feel like I’m too old.

My being burned the first time basically made me be honest, not just with myself, but with others in a way that I think enabled me to have success the second time around.

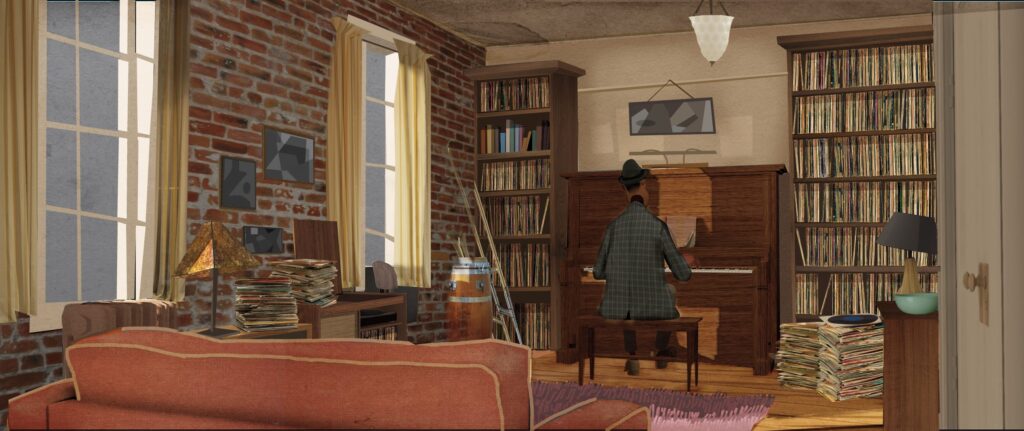

This concept art by Bryn Imagire shows Joe, a music teacher with big dreams, at the piano in his apartment in Queens. The music for Soul came from bandleader Jon Batiste. Image courtesy Disney/Pixar.

Kemp Powers: “Often the relationship you have with your barber is going to be the longest relationship you have with anyone in your life.”

Chapter 7: Going where no one’s gone before

How can you innovate on your craft? Assemble a team of trail-blazers

KEMP POWERS: I was a fan of Pixar from the very first Toy Story. I remember there have been times when even knowing how good Pixar movies have been your jaw drops. I remember seeing Finding Nemo, and the water in Finding Nemo, the way they modeled it. I was just like, wow, this is incredible.

One specific thing was Monsters Inc. There’s a scene where the Sully character gets banished to the North Pole. He’s laying in the snow and his fur is blowing. The way they animated the fur, I mean, my jaw dropped in the movie theater.

And so, I told Pete Docter, I said, “Pete, oh man, the opportunity to see Black hair,” something that is rarely dealt with in animation at all. And when it does, it’s the lowest common denominator, the simplest version of it. But to see different styles of Black hair rendered with that level of Pixar detail would bring tears to my eyes.

I said to Pete and Dana in the beginning, that I’m just one person who happens to be Black. I don’t speak for, I can’t cover for, all of the Black experience. I was never really tasked with having to do that. From the very beginning, there were always tons of different consultants brought in. I mean, look, there were things that I learned about lighting Black skin from some of the consultants that we brought in.

Oscar-winning cinematographer Bradford Young, second from right, meets with Soul film crew members including Steve Pilcher, Bryn Imagire, Britta Wilson, Jaclyn Simon, and Ian Megibben, on February 5, 2019, at Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, Calif. Photo by Deborah Coleman / Pixar

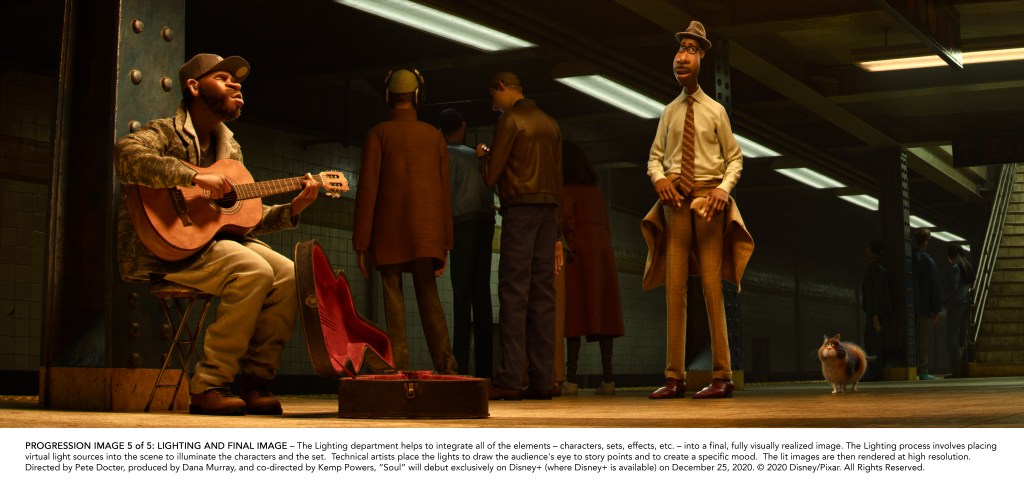

One of them was Bradford Young. He’s the first Black cinematographer to be nominated for an Oscar for the film Arrival. He basically gave several talks to our DPs about his philosophy and his techniques for lighting and how they really show off different complexions of Black skin. Our lighting department really took that to heart.They started doing lots of different things that have never been done in Pixar films as far as lighting goes, including recreating natural single source lights. You see characters cast into darkness in ways that you never really did.

I think the lighting is a big part of the unique look of particularly the human world in Soul. Not just the characters, but the backgrounds, and the buildings, and everything. Because of how accurately it does light the environments and how it lights the Black characters’ skin.

The Lighting department helps to integrate all of the elements – characters, sets, effects, etc. – into a final, fully visually realized image. The Lighting process involves placing virtual light sources into the scene to illuminate the characters and the set. Technical artists place the lights to draw the audience’s eye to story points and to create a specific mood. The lit images are then rendered at high resolution.

Chapter 8: When it’s all spliced together

How do you land on the best possible version? Try and try again.

KEMP POWERS: I can honestly say I’ve seen 10 different versions of Soul. There are versions of Soul with characters that aren’t even in the movie that you saw, I’ve seen four or five different endings of the movie. I mean, but the thing is we can’t land on that version that’s the best, unless we try those versions that just don’t work. It is very amorphous. It is like free jazz. It is like abstract art until it’s all spliced together and done and you go, “I can’t believe that worked.”

The “Soul” filmmakers, from left, producer Dana Murray, co-director Kemp Powers, executive producer Kiri Hart and director Pete Docter meet on March 4, 2020, at Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, Calif. Photo by Deborah Coleman / Pixar

Chapter 9: The First Screening

How do you know if your work hit the mark? Ask real people what they really think

KEMP POWERS: Look, for me, everything was at stake. Pixar’s never done test screenings for an all Black audience. So this was a first for them.

We had a version of the film ultimately that I was incredibly proud of – like incredibly proud of this version of the film. It was a very rough version of the film as well.

And there were people who came into the screening suspicious, suspicious of Disney, suspicious of Pixar deciding to have a Black protagonist, suspicious of what they would do, their treatment of said Black protagonists.

It was probably the most anxiety-inducing moment in the entire creation of the film for me was sitting through that screening.

I had been fighting for a lot of things behind the scenes coming from this place of like this is important from a Black perspective. And if that audience rejected it, it would have really established that the old way of doing things was the way that it should have been done.

I think Kiri Hart, our executive producer, probably had similar anxiety because she’d been fighting for a lot of the same things that I had done, and we’d won a lot of those battles.

During the screening of the film, we actually sat amongst the audience. That was actually amusing because, you know, I’m Black. So I’m just sitting in the audience, but when the rest of the Pixar people came in, you could see the audience was looking at them like, “and who are these people?”

So after the screening, they randomly select a group, I think it was about 40 people from the audience, and bring them into another theater.There’s a camera set up. So we’re sitting in one theater, watching a group of people in another theater, a moderator comes in and just peppers them with questions.

Thankfully, the audience watched the film, and they loved it. The kids got it, and the adults seemed to enjoy it. Sometimes people would say specific things like, “What was your favorite scene?” And a bunch of people were like, “Oh, the barbershop.” And I was just like, “Whew.” And one person said like, “I love that scene in the barbershop more than I love the movie Barbershop.” And I was like, “Oh, what a relief.”

Hearing those people who said they came in suspicious of this particular film won over by this film and saying how it represented them in such an authentic real way, how they connected to it, how it made them think about their own relationships and their own families, man, it felt so vindicating. It started off as the most anxious I’ve been in the entire process and it ended as the most relieved I’ve been in the entire process. Man, I needed a drink after that screening.

“Anybody else notice the “cookie” can in Soul?” C. Heard tweeted this small, true detail.

Chapter 10: The stories I want to tell now

KEMP POWERS: With Joe, I started with myself to be perfectly honest. Mining what I knew about life was kind of my way into the story.

Some of the works I love the most, I also see as being tied to the personal experiences and lives of the person who created it.

Pixar films have a lot of emotional moments, Everyone would say that in Up, it’s the first 10 minutes, the sequence known as Married Life. Everyone gets emotional at the same point in that movie. What we saw in our preview screenings was that different people got emotional at different moments in the film. My most emotional moment in the film is actually that moment with Joe and his mother. Seeing Joe understand his mom and seeing Joe’s mom understand him and still be proud of him really touches me on a personal level because it’s a version of a conversation I’ve had with my own mom.

My mom retired as a nurse. For many years, she just couldn’t wrap her head around someone writing fiction for a living ever being stable enough to like buy a home or put their kids through college. I can’t count the number of times that my mother has said she’s just worried about me.

From where she’s sitting, I understand why she would think that because at the end of the day, all of us in this business, we’re kind of all doing the impossible.

When I got into the Writers Guild of America, years ago, they do this orientation thing where they bring all the writers in and then they give you a lecture. They say, “Statistically speaking, it is harder to gain membership in this guild than it is to be a professional baseball player.” Now, when you put it like that, if you go to any public school in America and ask the kids: “What do you want to do when you grow up?” If they tell you a pro athlete, what would you probably tell those kids?

You would say, “Okay, that’s nice, but you probably want to have a backup plan in case the pro athlete thing doesn’t pan out.” Why? Because you know how statistically virtually impossible it is to make the cut. How phenomenal an athlete you have to be, what incredible breaks you have to have, the support system you have to have, all the things that need to break your way in order for you to become a pro athlete.

So, I don’t know. When you hear someone tell you that it’s statistically just as hard or harder to be a screenwriter, I suddenly understand where my mom is coming from.

Because I’m a bit older, I feel like I have a limited amount of time to tell the types of stories that I came into this business to try to tell.

I want to make everything that I do count. Everything I do isn’t going to be a success. I’m going to have my failures, and I have had my failures, but I just want to be able to put myself into things a hundred percent and just not be phoning it in.

If a story doesn’t speak to me on a personal level, then honestly, I’m wasting the time of the people who want to hire me, because I don’t believe the most talented person is the best person to tell every story. I think the person who has the most passion for that story might be the best person to tell the story

In this storyboard from Soul, we move from a dimly lit jazz club to a city street scene – and to a moment when the main character gets a second chance. Concept art by Carlos Felipe León. Courtesy Disney/Pixar.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Kemp, for so generously sharing the story of his creative journey with Soul. If you want to share it with others, send them to sparkandfire.com/soul.

And I want to thank you for listening. I hope you heard things in Kemp’s story to inspire your own work or practice. Whether it’s the way he said “no” to the projects that were wrong, so he could embrace the ones that were right. Or the way he mined his own experience for the authentic details that could breathe life into the story.

Maybe you’ll find yourself looking for the “note behind the note” next time you’re interpreting feedback — to find the kernel that rings true to you. Or maybe you’ll think of Kemp the next time you’re writing and writing and writing (or designing, or drafting, or shooting) — and remind yourself that you can only land on the best version of a work by cycling through the ones that aren’t right.

Kemp is proud of how he fleshed out the character of Joe’s mother, building on his own relationship with his mom. Concept art by Daniel López Muñoz. © 2020 Disney/Pixar.

About the Creator and Host