Creativity starts with play

How do you change the creative brief? You start with play. The designer Thomas Heatherwick was asked to create a monumental public work for the plaza of vast new development in the heart of Manhattan. The expected route would be to copy what’s worked before on other plazas in other cities – a statue, a fountain. But Heatherwick knew he had to push past what was expected. Spark & Fire follows the journey of “Vessel,” a massive piece of public art, from its roots in traditional Indian forms, to its sophisticated construction and multi-year assembly, to its reception by the public – a complicated story that is still unfolding. It’s a story of creative bravery, play, and persistence – at the drawing board and in the meeting room.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Playing with purpose

- Chapter 2: The pitch meeting

- Chapter 3: Hunting for ideas

- Chapter 4: The breakthrough

- Chapter 5: Building where no one has built before

- Chapter 6: The materials that bring it to life

- Chapter 7: The hardest problem was literally the last mile

- Chapter 8: The theater of construction

- Chapter 9: The public response

- Chapter 10: Open to the public

- Chapter 11: At the heart of it

Transcript:

Creativity starts with play

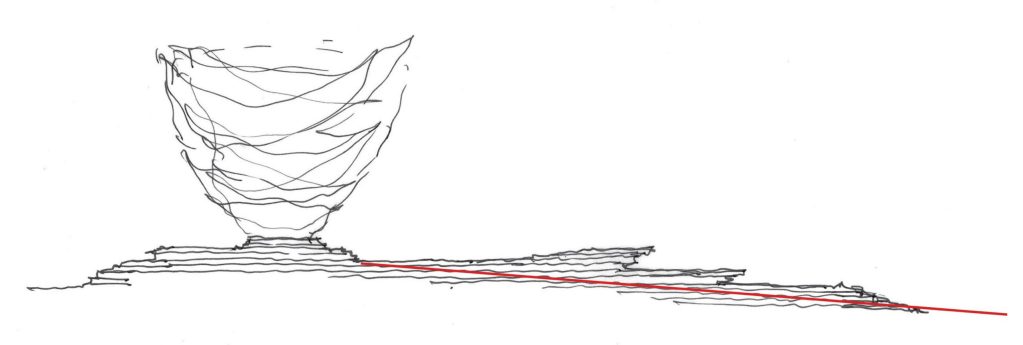

An early sketch of “The Vessel,” showing its placement on the sloping site of Hudson Yards, which tips gently down toward the Hudson River. Image: Heatherwick Studios.

Chapter 1: Playing with purpose

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: When my team and I sit down at the beginning of a project, and I know this maybe is going to sound bad, but we start by deciding what we don’t want to do. And I know there’s this view of creativity as a beautiful, smiling, positive thing. Often, you have no idea what you are going to do or what you might want to do, but you can be clear what you really feel is the wrong thing to do. And that jumps you forward. That negativity is phenomenally positive.

If you say, well, what if we didn’t do that? It starts to lead you towards what you would do.

As a child, I remember looking at climbing frames and thinking how ugly they were. I’d been brought up with this experience, which was that children’s play was this thing that happened in a caged zone within a park. When we think about creativity in adults, we know now more than ever that play is part of what leads to creative thoughts. The way we work in the studio, in a sense we’re playing together. We’re playing with purpose, with focus that leads towards a solution. And so the idea that plays only for children seems absurd.

Why don’t we make a climbing frame for everybody, for children and adults?

The idea felt an outrageous idea to propose to people who had asked for a sculpture.

JUNE COHEN: That’s architect Thomas Heatherwick, and he’s about to tell us the story of creating the Vessel, a building in Manhattan that opened to the public in 2019. Now, I should clarify that the Vessel isn’t exactly a building, but more of an open-air structure. It looks like a honeycomb, it’s 16 stories high and copper-colored. It’s made up of interconnected walkways and stairs. And exists entirely as a public space for people to climb and move through.

Thomas himself is known for deeply imaginative works. From unusual retail spaces like Coal Drop Yards in London to surprising structures, like the Rolling Bridge in London, the “Seed Cathedral” at the World Expo in Shanghai, and the new floating park in New York called Little Island, which opens this spring.

Before we begin, you should know two things: First, the Vessel is located in Hudson Yards, a new neighborhood on the west side of Manhattan, near the railroad lines. Second, the original brief asked architects for a sculpture in a plaza. Thomas pitched something quite different.

And finally, in the grand tradition of unusual building throughout time, from the Eiffel Tower to the Twin Towers, The Vessel sparked a lot of lively public debate as it opened. This is Thomas’s story of bringing it to life.

I’m June Cohen, cofounder of WaitWhat, former Executive Producer of TED, and your host for Spark & Fire. But this isn’t an interview show. It’s a story, told entirely in Thomas’s own words. It’s set to originally composed music on the prepared piano. For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com/vessel.

[Theme music]

“The Vessel” and the exterior of the shops and restaurants at Hudson Yards. Photo: Francis Dzikowski for Related Oxford

Chapter 2: The pitch meeting

How do you change the creative brief? You start with your beliefs.

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: The time had passed for plunking sculptures in plazas. That felt like an old-fashioned mode. We were on the 19th floor of one of the towers at Columbus Circle, meeting the founder and the client team for the Hudson Yards project. I don’t like the feeling of meeting boardroom table things. So I try to do everything I can to not sit face to face across tables like that.

And you’re just there thinking, oh really, am I going to say this thing? I don’t even know this person and I’m about to kind of put a spanner in the logic. How do you not seem like a negative person to someone who doesn’t even know you? First time you’re ever meeting them

I remember proposing, with absolute sense of doom, that this clearly, would never happen. But this was what we believed in. I initiated a line of conversation and questioning saying, are you sure you want to do what I think you’re asking for? Because isn’t that actually a very familiar format.

Right, we’ve got a space. What should we do with this space?

Oh, what’s been successful before?

Did you see what they did in Chicago?

Oh, well, in Chicago, there are some incredible monumental works,

Where the Millennium Park was created was very successful. There are a couple of really amazing works of art there. So many cities copy the formulas of other cities in the belief, well, that is successful so it would probably be successful here.

Whereas my belief is the most successful things say, bravo, fantastic. I love what you did, right? How do we do something with a similar level of ambition here, but not the similar formula? If I was you, I wouldn’t do a freestanding thing you walk around and sort of admire, and I was almost trying to get myself out of the door.

That conversation grew from something which originally might’ve felt like this is something to wriggle out of, but the positive response from the team it related of saying, well, yeah, and real recognition, a sort of spark in the eye and a response that was so encouraging that made us feel that there was space for something that could maybe be extraordinary – not for extraordinary sake, but for public sake.

The idea of plunking statues and fountains in public plazas is as old as cities themselves, and designers have had a couple of millennia to ring the changes on that combination. Thomas Heatherwick knew he had to push for something … else. Image: Catholic Total Abstinence Monument, 1876, from Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park.

Chapter 3: Hunting for ideas

How do you explore every possible direction? You stay together.

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: Well, I work very much by myself. Sorry, the opposite. I don’t work by myself. I’m energized and inspired by dialogue with others.

There’s the image given of geniuses who have fully formed ideas that spring out of their head. And all they need to do is achieve that as if you press the magic button. And for us in the studio, the designing isn’t happening in me, it isn’t happening in someone else, it’s happening in the bouncing within a conversation between us.

I might be sitting in the middle of that conversation, but I would be just as likely to be asking the person who joined the studio a month ago for their thoughts and observations, just as much as my beloved colleague who I’ve worked with for 18 years, who’s a brilliant designer.

We were scratching our heads and both standing and sitting as a group of six, seven, eight of us, who would come together and then pull apart, hunting for what the right answer might be and not sure if we would come up with a right answer. Racking our minds and thoughts and stories and places we’ve visited, wrestling around with design problems that feel worth trying to solve.

We were there in this studio, which is essential for provoking the thoughts that sometimes can lead to great projects. A big open space. It’s raw concrete. We have a very large workshop, which allows us to never forget that our role is we are makers.

Many buildings over the last half a century or so have lost that maker’s passion. And I feel very lucky to work with a team of incredible people who have maker’s passion and are interested in the soulfulness and materiality of things.

We never develop great projects without joy in that process because our projects, while being extremely serious such as the cancer care center we’ve just finished, are the root of them also about joy. And if you’re not exploring joy as a notion and how to engage people, if you’re not actually living that in the process, I don’t believe the project itself will have the human qualities that we are aspiring to and what we do.

There’s a brief that you might be given, but you’re then taking that and you’re swallowing that, and you really let your studio’s digestive system get in on that. And then that metaphor is going a bit wrong because it’s now got to go somewhere once it’s in my stomach that it shouldn’t go. But in effect, you’re then producing a manifesto, something that’s going to act as your guiding values.

We all contributed to those values. And then together, we were like a pack, a little team hunting through and testing the different physical ways to realize those values into a real project.

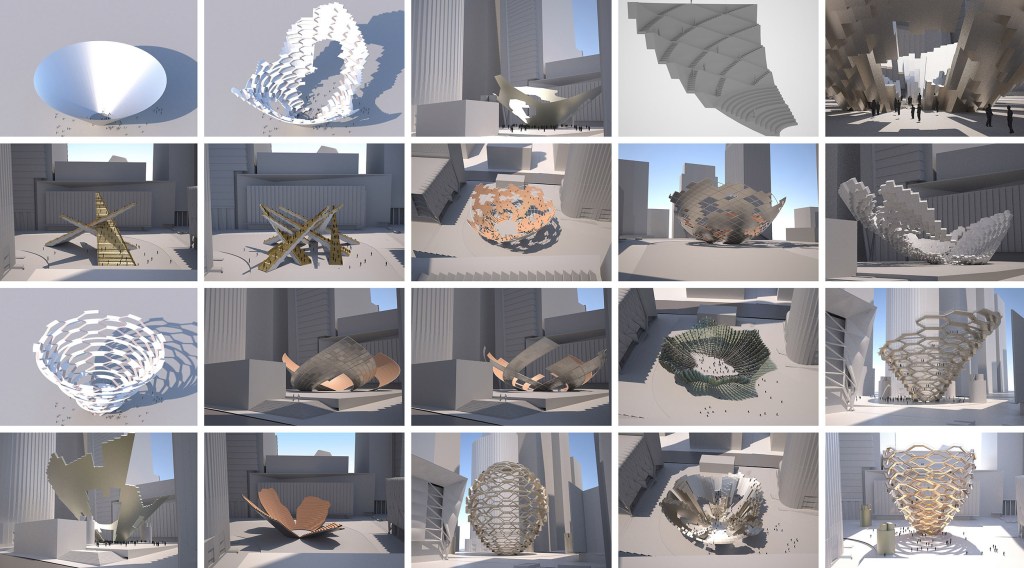

A digital exploration of early shapes and designs for filling the plaza at Hudson Yards. Image: Heatherwick Studio.

Chapter 4: The breakthrough

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: As the best moments in this studio are, I can’t tell you whose idea it was. I can’t tell you. And I don’t think any one of us is quietly thinking, “Well, that was my idea.”

We started researching the history of this location. It was a place that was going to be entirely new. And there was an urge to find a way to clarify a heart to a new piece of city. And it’s so rare that new pieces of city have a chance to be made.

Most of the world, in a sense we can say is confusing, but it also isn’t. It’s deeply familiar even if you’ve not been to this or that district or this city, you walk into and go, oh, yep, there’s the big office buildings. Oh, yep, there’s the artwork on the plaza. Oh, yep, there’s the water feature. Oh, yeah, there is the food truck. You just go one by one, tick, tick, tick, like a tick list.

Could there be something where it didn’t press any of those buttons?

So we got interested in the theater of togetherness. How do you convene people and make meaningful human experience? We are all in some kind of public theater. Some kind of public dance is going on between us. And so this idea of a promenade, and equally have an amphitheater that would bring people together where you could have a thousand people, more than that together, where you yourselves, everyone on that, they were the performance somehow.

We had been puzzling over the power of a bowl, an amphitheater-like bowl. People could be in layers inside a bowl and how extraordinary socially that would be. The problem with a bowl, was that it had a back and the outside turned its back on New York around. It felt rejecting of the context. We were looking at a screen, and then we started drawing, and there was this bouncing backwards and forwards between us and we were doing overblown, working too hard ideas. And there was a breakthrough.

One of my colleagues had found some images of these stepwells structures that have been built in India. They were dug very much down into the ground, but used flights of steps to make a textile-like pattern. It clicked.

Instead of that being underground, if you took that out of the ground and took away the gaps between the stairs, we would be simultaneously making a bowl that would bring people together, but also looked outwards at the same time. And that led to this notion of a mile of space. I mean, we became so excited. We thought, “We could make a mile of space if we wrap it round like this.” And simultaneously, be making an atmosphere that is room-like, but is outdoors, and a chemistry between strangers. It was a moment where we just thought, “Yes, that would do it.”

The mesmerizing repeats of an Indian stepwell, cut deep into the earth, create a pattern that implies community and gathering. “Stepwell,” by Andrea Kirkby, via Flickr. CC 2.0 license

Chapter 5: Building where no one has built before

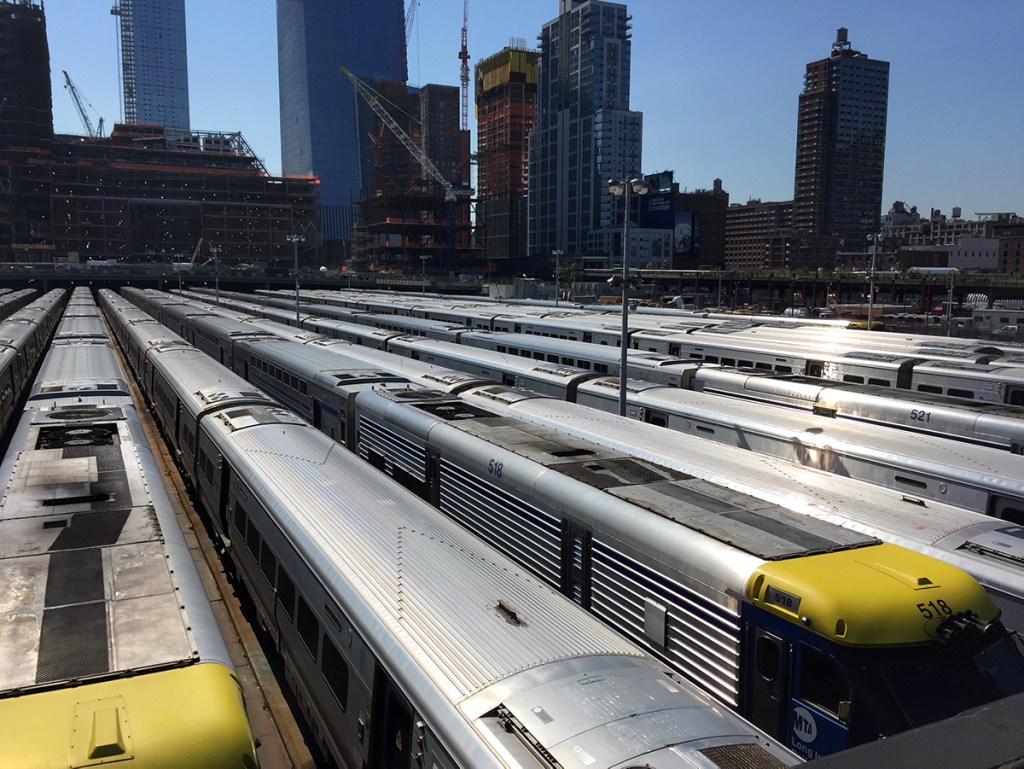

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: Something that people misunderstand is the phenomenal, incredible achievement of building at all in that location. Above railway lines, coming out of Penn Station. There’s about 25 or 30 lines there and that sort of sterilized that part of New York for so long. That’s why there was not a piece of city there before. The thing that people aren’t even aware of is that you’re not standing on the ground. You’re standing on a huge platform.

Manhattan is made up of layers and layers of city. And so the load you apply, you press down on any bit, it’s got the risk of doing real damage to levels below whether they are steel bridging decks. You don’t even realize there’s a deck or a bridge.

Major, major, multi, multistory buildings, all being built above railway lines that kept working the whole time. It’s such a technical achievement to build a table across all of that. And in the middle of that table is our Vessel.

A snapshot from July 206 of an under-construction Hudson Yards, viewed from the High Line. The buildings are sited on a platform over a massive, very active train yard. Materials for the Vessel have not yet been moved into place.

Chapter 6: The materials that bring it to life

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: So to engineer a project at this scale, 150 foot tall, if you loaded it fully, could easily take one and a half thousand people if they were jumping up and down. To do that on a structure that is springy looking – it does look like in an Indian restaurant, the metal bowls that their naan bread might come in or something like that – is an extraordinary thing to engineer to be stiff enough and not vibrate in ways that could damage the structure over time.

You spend a lot of time making visualizations and models. To be able to take the weather extremes that New York has, which the swing, I think I’ve been hottest I’ve ever been in my life in New York, as well as the coldest I’ve ever been in my life, in New York. That meant that steel became a material that felt appropriate for this. And we knew it could be done really, really well.

So often buildings are gray, or bluey gray, or greenie gray, or brownie gray. We’re surrounded by buildings of that nature. And it felt that there could be a role for something that had intensity and warmth.

Materials like gold color or silver color sort of felt so obvious. Whereas this copper color felt like it had warmth, but also it had other levels of sophistication to it.

The joy that the mirror polish gave was that because they’re all curved, you see everyone who’s on it. It reflects back people looking, but it also catches the reflection of people on the vessel. So when you look up and might typically just see undersides, you’re actually seeing the heads of everyone walking around on it. And so when you stand and look up at it, it’s always alive.

I remembered the song, I think it’s an Andy Williams song, which is called “Music to Watch Girls By.” The words were: the boys watch the girls while the girls watch the boys who watch the girls go by. And this sense of that chemistry. From the very first moment, we always were excited to have this curving elevator so that even people who maybe weren’t so able bodied and able to use the steps would theatrically rise up in a curve. There are hardly any other elevators in the world that curve.

We’d equally wanted to celebrate for a non able-bodied user, them actually have a route up the structure that would be the envy of the able-bodied people.

And this, you get the best view because it’s right in the heart of the room of the Vessel itself. What you’re walking on is simple concrete, simple concrete blocks precast. It’s job is it’s a servant. It’s a platform for life. We wanted it to be just tough. And it’s designed to be there in a hundred years.

Explorations for finishes on “The Vessel,” including its distinctive shiny copper. Photo: Heatherwick Studio.

Chapter 7: The hardest problem was literally the last mile

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: It was amazing how well it flowed to make the piece, get the pieces on these giant barges, and get them to Manhattan. The hard thing was getting from Manhattan to Manhattan.

The piece was made in Italy, just outside Venice, in a place called Monfalcone, by an incredible company called Chimilai. It was really exciting working with people who are used to building major pieces of infrastructure for this planet. They normally make gigantic doors for international canals that go between the Pacific and the Atlantic. They are making vast structures, and they had the level of quality and engineering skills to be able to make steelwork at this scale.

They genuinely were looking at making this as one object to transport in one bit. They could have made this 16 story high structure as one thing. They could have moved that. They could have brought it by sea, but it wasn’t possible to get it from the Hudson onto our sites. There was no lifting method you could do to do in one big go.

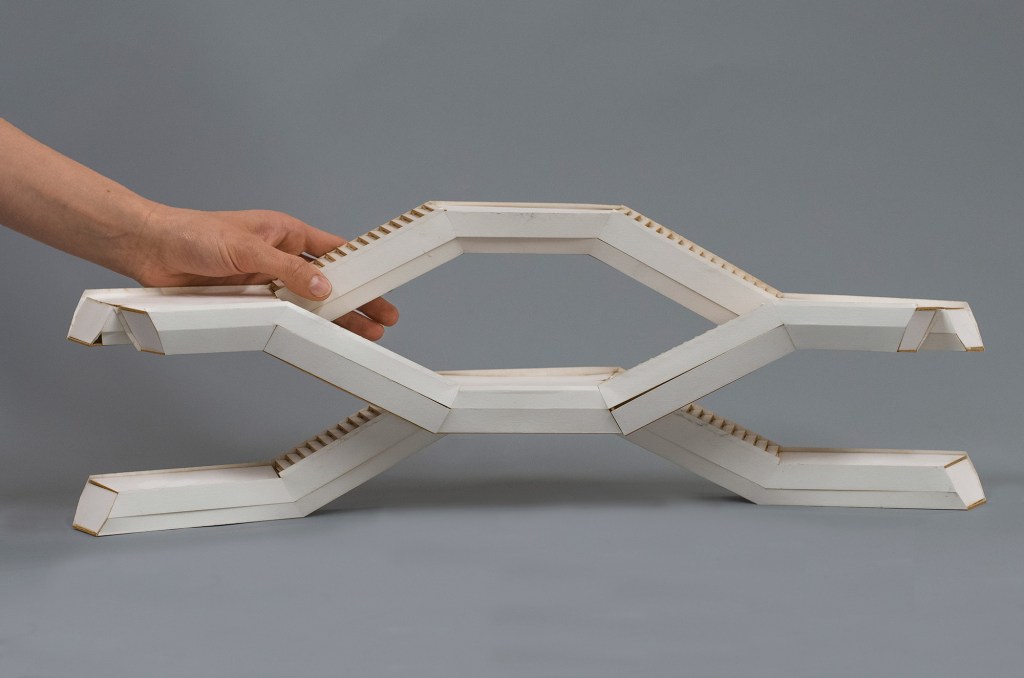

So the engineers worked out that in order to transport it and fabricate it in manageable chunks, the project should be divided. So there’s 80 of these central platforms and then springing off it are these sprigs, like wishbone ends that come off. And the outcome of this platform with the staircase sprigs coming up and down at the sides is like a dog bone. You could transport them on a barge from Italy across the Atlantic, but you also could maybe get that through the streets of Manhattan to Hudson Yards.

They were just a few hundred feet from where they needed to get to, to actually get from the water to that location that was there on the West Side. You would have seen a kind of lumpy, steel dog bone that’s sort of hanging over the edges of a very big lorry, and the shiny precious metal would have been covered over because we needed to keep it protected from damage as much as we possibly could. So you’d have probably just thought it was a bit of building stuff from the building stuff shop. In effect, it was in plain sight. These bits would have gone past, and you’d just think, “Part of New York’s building boom,” that goes on.

Getting the permissions to go across road bridges and railway bridges, because they’re very heavy pieces, and if at any moment any load was above an acceptable amount, everything could grind to a standstill and stop.

So special sensors, hundreds of special sensors, had to be fitted to all those bridges to analyze as lorries drove over them, making sure that no existing bridge had been damaged in the process of transporting these pieces.

So it was a very slow, painful process, just this moving piece by piece to the site and then placing them down by the railway lines, and be able to just be lifted and constructed directly onto the foundations that had been cast threading down through and past the railway lines down into the ground.

Pieces of “The Vessel,” ready for transit from Italy. Photo from Heatherwick Studio. Watch a time-lapse of this process from ArchDaily.

Chapter 8: The theater of construction

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: In a sense, it’s already a family member. It’s already existed for years before it physically exists. We waited till all the bits were in New York to actually properly tell New York what was happening.

And that was the moment when the amazing dance group, The Alvin Ailey Group, that has both professional dancers and hundreds of amateurs, composed a special choreography piece and performed it in front of where the Vessel was being built. There’s a joy to keeping things and then letting them be a surprise.

So then there’s the proper theater of construction. That seemed the moment where it would be really nice for people to engage in these pieces as they gradually got assembled in front of the city’s eyes. And you didn’t want to build a container over the top. You didn’t want to sort of create a giant hoarding. You wanted to let people see it as it came together like this very complex, sophisticated jigsaw.

It took eight months for those pieces to all get bolted together and get that right. Then there was a year after that to properly put in all the paving and balustrades and everything and get it ready.

I was walking up it even before it was all assembled. There are the things where you sort of are ticking off in your brain. You go, “Oh yeah. Okay. That is there.” And then the things where you’re still wondering, we’re thinking, “Oh, what about that thing?”

Whether it would be too tiring to walk up? There’s 154 flights, 2,500 steps. Was it going to feel as if this was hard work? You realize that the mind and the imagination was so engaged with wondering that you had wandered up half of the structure before you even realized your legs were working. That was exciting to feel like, “Yes. Okay. No, we’re not going to have any problem.”

The biggest question is even when you’re walking around by yourself, it wasn’t meant for by yourself. It was meant for the city. It’s meant to have a thousand people on it. And that’s the thing that you can’t really know. And you can’t judge its success by yourself. You’re still hoping and predicting for that hoped use, which is for people to find joy and provocation in it for themselves in their own ways. And that’s out of my control.

A test fit of pieces in the Cimolai yard in Italy, in July 2016, before the pieces were transported thousands of miles by ocean – and one last agonizing mile across Manhattan. Photo: Heatherwick Studio

Chapter 9: The public response

How do you learn from criticism of your work? You learn to expect it.

JUNE COHEN: It’s human nature when something is different than something you’re used to to have an opinion and to have a response. And I welcome that.

We knew that there’s always going to be controversy about whole developments. People have always got good things and bad things to say about city development when it’s done by private developers.

Something that we’ve found in the United Kingdom is that there is an absence of cities commissioning things anymore. After the Second World War, there was a need to make lots more housing and workspace and shopping space, now all the different things that were needed, and countries took that on, and cities took that on. But then some absolutely sterile, un-human places got made in that rush to rebuild that cities undertook. And then it seemed to grind to a halt, and confidence was lost. So it shifted across to the private sector to make place.

The Vessel is part of a privately owned public space. But it’s space that never existed before. It was created by the entrepreneurial spirit of people coming together to make it. But that can often be portrayed, caricatured, as somehow cynically restrictive, and that this is not a true public place.

That criticism can also miss really well intentioned, very intelligent place makers who, yes it is privately created, but where the spirit is actually that you’ve got to make human good places for people to even to make any business sense. You’d be stupid not to. That’s what we hold to is that it must make sense to make a human-centered place, whether that’s a city or an organization, we always try to assess project by project, about whether we can engage. And that’s why it felt so important to us that it was free.

And that took quite a bit of persuading and arguing the logic, there was a logic saying people could pay a little bit for the expenses of cleaning it and guards. There was no urge for it itself to make any profit. We just argued it must be free, in the same way that it’s free to walk in Central Park or free to walk on the High Line or go on Hudson River Park on the different piers. And the people who made Hudson Yards believe in that too now. So that’s great.

For Christmas 2019, the pastry chef at Citarella imagined the Vessel in cake. Find more images of the Vessel in situ on Hudson Yards’ Instagram account.

Chapter 10: Open to the public

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: It’s a scary thing when there’s something that you’ve worked on for many years finally realizing its goal of meeting the public. You will have spent years imagining everything you need to think of. And then suddenly you’re there and you’re living inside it.

The project only really came alive for me until it had hundreds and hundreds of people on it, because that was the point. The joy for us was seeing how it would be used, because just as in play, you don’t design every aspect of how someone will play with something. It’s there for them to interpret how they want, whether that’s by fitness freaks or people wanting to get married on it or develop performances specially for it or interacting with musicians and actors in ways that you wouldn’t otherwise ever do in a normal theater or concert hall setting.

You and your husband or someone and their children or a group of work colleagues can be intimate with an object that is city scale. It’s been fascinating watching those different responses, and it’s sort of no longer your project, you’re handing it over. It’s everybody’s. It’s New Yorkers’. And that takes over.

The forces that drove The Vessel were about bringing people together. Looking up at somebody looking down at somebody, there’s an auto humor that happens when people have an experience that they haven’t had before.

And quietly just watch the people as they watch you and watch each other, as the cheesy Andy Williams song goes.

The interior of the Vessel, looking up at the skyline. Image: Michael Moran for Related Oxford

Chapter 11: At the heart of it

THOMAS HEATHERWICK: I spoke to someone three days ago, and they said to me, “Cities should be gardens for growing better people.” And I loved that expression. That was from an urbanist called James Rouse. It felt to me that this is just one interesting plant within the garden of a city, and that this isn’t the answer to a city, this is an ingredient, and this adds color, and gives vitality. And it’s okay if somebody likes it or doesn’t like it. But it’s the physicality of that experience and the social dimension of that, I believed, had its own currency that I couldn’t change or affect. There it was. It existed.

Wow. The Hudson Yards gave us a chance to do such a different project than anywhere else in the world, and gosh, New York has a confidence and a culture that led to a project we would never have done anywhere else on this planet.

Nothing else I’ve ever done, me and my team have ever done, has been like this. So it was a breakthrough for us of typology. No one’s done something like this. It’s a different kind of a project.

The design that became The Vessel, in a sense, is a giant amphitheater, but it’s perforated, we’ve cut it through so that it’s looking outwards as well as inwards. And the development of the design was very much led by the room that is at the heart of it. And for a big length of time during its creation, people were always seeing the outside. And I kept going, “No, it’s not about the outside, it’s about the inside.” When people get inside, that’s when the project will actually come alive and be complete.

When The Vessel opened, I must admit I didn’t feel scared of how it would be received, because I knew I could trust the 12-year-old in me, and the 12-year-old in all of us.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Thomas for sharing his creative journey. If you want to share it with others, you can use the link listen.sparkandfire.com/vessel.

A small model of “The Vessel” shows the toy-like charm in the way the pieces fit together. Photo from Thomas Heatherwick Studio