Tell a universal truth

Stephen Schwartz has a motto for songwriting: Tell the truth, and make it rhyme. In this episode, Stephen tells the story of composing the Broadway musical Wicked. Not only does Stephen reinvent a beloved classic for the stage, he also commits to drawing out the universal truths — like the experience of friendship, betrayal, and love — that connect us all. This allowed Wicked to resonate with audiences in a real way, making it one of the most successful musicals of all time. Stephen’s story shows that when your work expresses a universal truth, the widest audience will respond.

Transcript

Table of Contents:

- Chapter 1: Tell the truth

- Chapter 2: The spark

- Chapter 3: Off to see the wizard … to get the rights

- Chapter 4: Why I had to write this musical

- Chapter 5: The nice lunch

- Chapter 6: What we knew from the beginning

- Chapter 7: How to get unstuck

- Chapter 8: How I start to write

- Chapter 9: The first reading

- Chapter 10: Writing the final song

- Chapter 11: It’s not working

- Chapter 12: We create the iconic song “Defying Gravity”

- Chapter 13: Opening night

- Chapter 14: The truth was in you all along

Transcript:

Tell a universal truth

Glinda and Elphaba lead the company of “Wicked.” Photo by Joan Marcus 2022

Chapter 1: Tell the truth

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: When I get asked, “How do you go about writing a song?” I have a glib response — but it’s really quite true — which is: Tell the truth, and make it rhyme. You don’t really even have to make it rhyme, but you need to tell the truth. That’s what people respond to. It’s so mysterious, but it’s really also very reassuring, that if you expose yourself enough, your heart and your soul and your obsessions and your doubts and fears, if you really tell that truth, people respond to it, if you tell it skillfully.

And what’s more: You think you’re standing naked before them. You think they know everything about you, but they don’t. They’re not seeing you. They’re seeing them.

JUNE COHEN: That’s the legendary composer Stephen Schwartz — and he’s about to tell us the story of creating the Broadway musical Wicked.

It’s Stephen’s personal story of reinventing a beloved classic for the stage — and convincing others to believe in it as much as he does. But what Stephen learns along the way applies to any creative in any field: When your work expresses a universal truth, the widest audience will respond.

As Stephen takes us on the journey of writing and composing Wicked, you’ll hear how he leans into universal truths that connect all of us – like the experience of friendship, betrayal, and love. He’ll show you how telling the truth to your team creates a space where great collaborations can thrive. And he’ll also share a universal truth about getting unstuck that anyone can use.

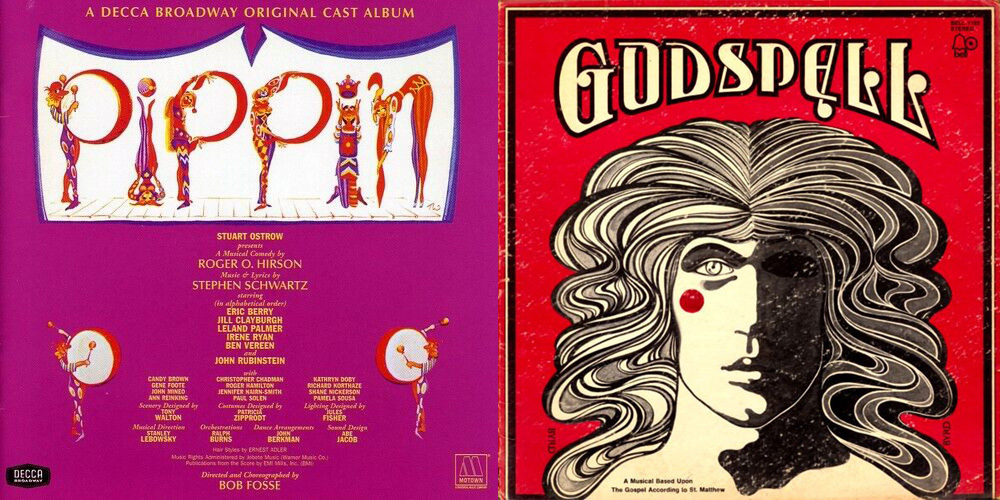

And here’s what you need to know about Stephen Schwartz and Wicked. Stephen has a career spanning five decades as a musical theater lyricist and composer. He’s written musicals that changed the landscape of American theater — like Godspell and Pippin.

As for Wicked, it’s broken nearly every record in theater history for ticket sales, making it one of the most successful musicals of all time. The story itself is a re-telling of The Wizard of Oz — from the perspective of the so-called wicked witch. Stephen adapted it from the book Wicked, written by Gregory Maguire. And to create it, he had to not only adapt an iconic retelling of an iconic story, but persuade a lot of people that it was a good idea. Time and again, he’ll come back to his mantra: “Tell the truth, and make it rhyme.”

I’m your host, June Cohen, and on this episode, you’ll hear original music composed for piano and guitar. For visuals while you’re listening, go to sparkandfire.com.

[THEME MUSIC]

Chapter 2: The spark

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: It’s so hard to be able to articulate why an idea hits you like the shaft of an arrow.

I happened to be on a snorkeling trip and one of my friends, Holly Near, said, “Oh, I’m reading this really interesting book. It’s by this guy Gregory Maguire, it’s kind of the Oz story from the Wicked Witch’s point of view. It’s called Wicked.”

All the hairs on my arms and the back of my neck stood up. And I just thought: That is the best idea I have ever heard for a musical.

Here is this iconic villainess. And all we really know about her, other than what she does in The Wizard of Oz, is that she’s called “The Wicked Witch of the West.” We don’t even know her name. And we have no idea what her point of view is. We have no idea why she’s doing the wicked things that she’s doing. So the idea of looking through her eyes seemed so exciting to me. I thought: Somehow I have to find a way to do this.

I called my lawyer and I said, “There’s this book called Wicked. I’m going to read it. But in the meantime, can you find out who has the rights?”

I worked my way up to getting a meeting with Marc Platt, who was running Universal Pictures.

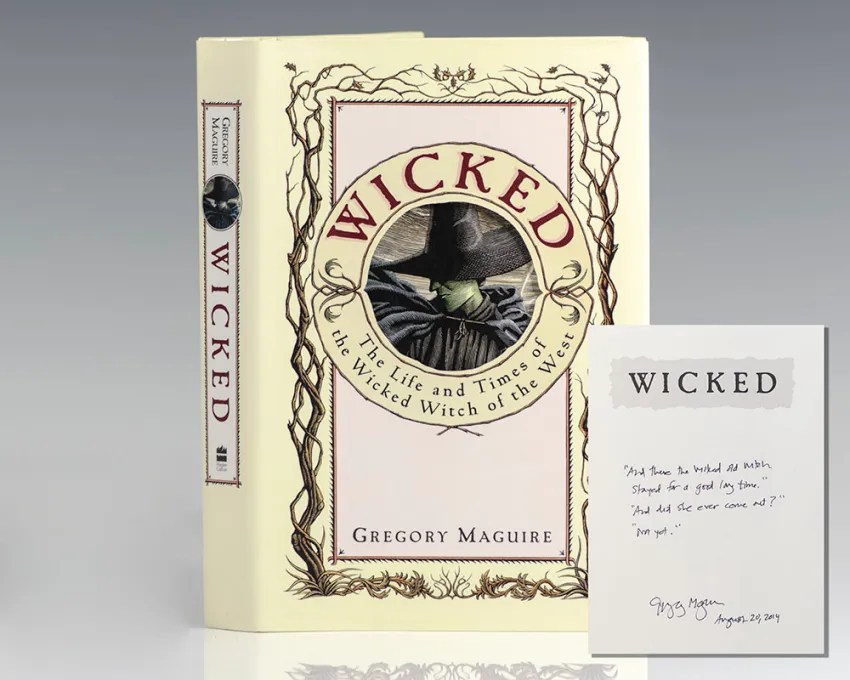

This signed first edition of “Wicked,” by Gregory Maguire, is listed at Raptis Rare Books. It’s signed with the final lines of the novel: “And there the wicked old witch stayed for a good long time.” “And did she ever come out?” “Not yet.”

Chapter 3: Off to see the wizard … to get the rights

How do you get permission to pursue your dream project? Speak your truth… and hope for a friendly audience.

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: When I drive onto the lot of a Hollywood movie studio, there’s something about it that’s quite intimidating, I have to say. It was a scary big movie executive’s office. Waiting for the secretary to let me in.

I knew that movie studios were not very interested in musical theater. It doesn’t pay nearly as much as a hit movie, and so on. I really thought: If this meeting didn’t go well, that was the end. That was the end of that journey. And I did not have very high hopes.

But if I were ever going to have a chance to develop Wicked as a musical, this was it.

I walked into his office, and before anything else was said, he sang “Corner of the Sky” to me.

Apparently he was a musical theater fan. He had been in Pippin, or Godspell, or one of my shows in college. He was singing a cappella. But the line is this: “Everything has its season / Everything has its time / Show me a reason and I’ll soon show you a rhyme.” So I knew I had kind of a friendly audience. At least an audience who would hear what I had to say.

I told Marc why I thought this project would not work as a film initially. And I told him why it had to be not only a musical, but start out as a stage musical. I said, “Look, everybody knows what Oz looks like on film. So, the minute it doesn’t look like that, you’re going to lose part of your audience. Whereas on stage, it doesn’t have to look like the 1939 movie.”

Also, so much of this story is internal to what Elphaba is feeling and what she wants — and that is just built for musical theater. In a movie, you’re going to have — what? a closeup on a green face? It’s just not going to have the same kind of impact.

And I also talked to Marc about how I saw the show, what I thought the arc of the story was, the things that were important to me about telling the story that I was passionate about.

He wasn’t instantly convinced. They were so far down this other road; they’d spent money. It really meant making a U-turn and coming all the way back to square one, and then going down another road.

Albums covers for Pippin and Godspell. Writing these two classic musicals was helpful in getting Stephen Schwartz a meeting at Universal Pictures, where he pitched his vision to turn “Wicked” into a musical.

JUNE COHEN: As Stephen made his pitch to Marc Platt, did you notice how he focused on the universal truths? Truths in the human story, truths about the media format. Now, in different fields, the truths themselves might differ. But it’s worth noticing how that universal truth becomes Stephen’s north star.

Chapter 4: Why I had to write this musical

How do you know you should fight for a project? You have more questions than answers.

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: After the meeting with Marc, I knew that it was unlikely that I would actually be given the rights.

I started trying to think of other iconic villains that might make a good character in a musical. I thought of the wicked queen in Snow White. I thought of Judas, but I felt like, well, I’ve been down that road already. Just none of them spoke to me, none of them were in my heart and soul the way Elphaba was.

The idea of Wicked just sparked in me so many of the things that I feel emotionally about. What appealed to me, first of all, frankly, was the title. It just immediately struck in me something I wanted to know more about. Well, what does that word actually mean? What is wicked? It already implied that things are philosophically, and politically, much more gray than we want them to be.

Then I’ve always been interested in stories that take a familiar character, and then spin them, and look at it from another point of view.

Then I’ve always been attracted to stories about outsiders who are longing to be part of the “in crowd,” and that character of the Wicked Witch of the West, who is green, immediately struck me as a quintessential outsider.

All of that stuff was instantly contained in the title of the book. I just knew: I have to get this somehow.

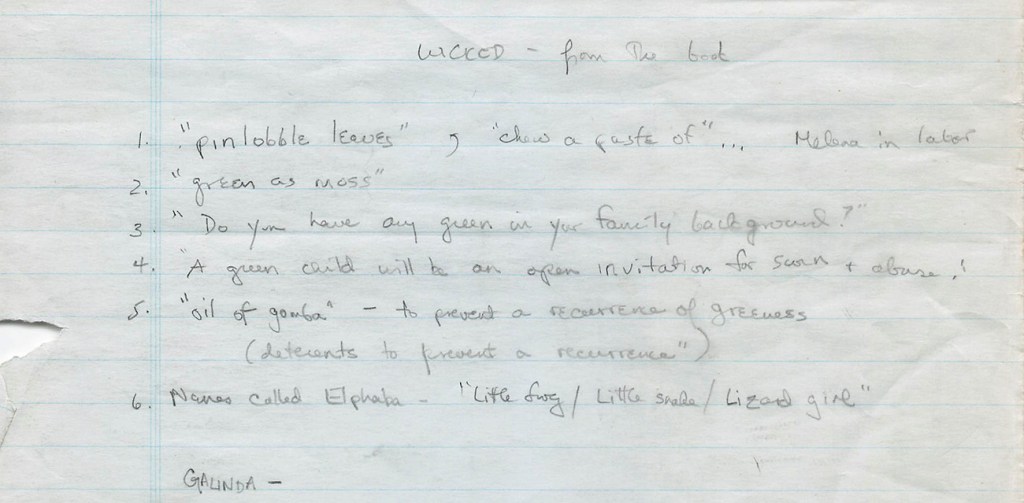

“Do you have any green in your family background?” Stephen Schwartz’ original handwritten notes as he read through “Wicked” — and begins to identify the themes and stories that will drive his songs. Click through to see all 5 pages of Stephen Schwartz’ handwritten notes.

Chapter 5: The nice lunch

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: I finally heard from Marc Platt. He decided to develop it as a musical if we could persuade Gregory Maguire to give up some of the money he was going to get when it was being made into a movie, and let us do it as a musical instead, a far more risky proposition, and one far less likely to yield any kind of income for him.

I got in touch with Gregory. He and his husband, Andy, who is a painter, were an hour away from me, and I drove up there to see him. He actually had sheet music from Godspell on his piano but was not going to show that to me if he didn’t like my ideas. And he had told Andy that if he liked what I had to say, and he was going to say, “Yes,” we were going to go out for a nice lunch at a certain restaurant nearby, but if he didn’t, we were just going to get pizza.

And we took a walk. I was so passionate about this idea, and I’d thought about it enough that I could really be articulate. I told him why I was the one to do it. And he agreed. We went out for the nice lunch.

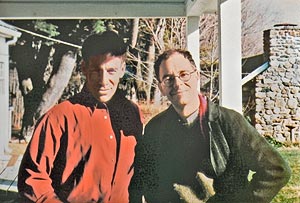

Stephen Schwartz visits Gregory Maguire to pitch his vision for turning Gregory’s novel “Wicked” into a musical. This photo comes from The Schwartz Scene, an amazing newsletter from Carol de Giere about all things Stephen Schwartz.

Chapter 6: What we knew from the beginning

How do you keep the truth of a project front and center? Find a collaborator who sees it too.

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: In the novel, Glinda winds up being the Wicked Witch’s reluctant roommate. That was such a funny idea. So I knew that that was going to be part of the show.

Gregory, in the novel, has the origin story of the Cowardly Lion. And so I thought, “Oh, wait, I want it to have the origin story of everything. I want to know, who is that scarecrow? And where did those ruby slippers come from? And how come she has that black pointy hat?”

A reader who likes Agatha Christie, and the Harry Potter series, I wanted the show to have that kind of construction, where there are revelations that happen, but the clues are planted in plain sight as you go along.

I know that I’m not a good book writer — which is basically the dialogue. I’ve never written my own books. And I just don’t think I actually possess that talent. So I knew I needed a collaborator.

I was thinking of female writers. It was a woman’s journey. And I just felt, well, she, the writer, is going to bring a different perspective to it that the most talented male playwright is just not going to have in quite the same way.

I knew Winnie‘s work a little bit because I had known her when she was a student in a masterclass at NYU. More than anything, I remembered a television show that she had created called My So-Called Life, which was built around a young woman character who felt like Elphaba to me.

It was very important to Winnie that the character of Elphaba actually do something wicked, that she not just be this misunderstood, saintly person. So we talked about that, and basically Elphaba steals the guy that Glinda is in love with, and she knows she’s doing it. She knows she’s breaking her friend’s heart, but she does it anyway. And that’s kind of wicked.

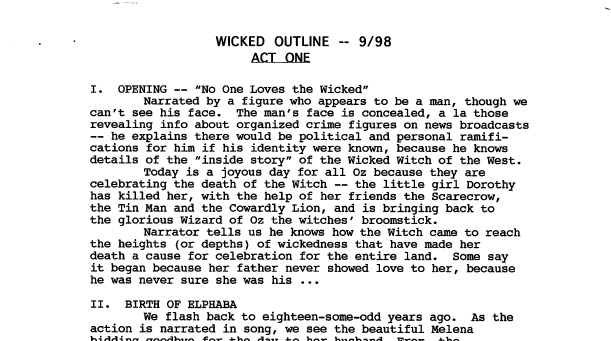

Deep in his planning phase, this outline of the musical was based loosely on the characters and beats in Gregory Maguire’s novel. Click through to see the full 6-page treatment that Stephen’s team shared with us.

Chapter 7: How to get unstuck

What do you do when you’re going nowhere with your work? Start wearing a different invisible hat.

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: All artists get stuck. But I have learned the secret to how to get unstuck. And it’s very simple. And I will tell you the story of how I came to learn this. I was working on one of the songs on Hunchback of Notre Dame for Disney, and I was having that sort of cliché experience of writing things out and then crumpling up the paper and throwing it on the floor. I just was getting nowhere. And I happened to have a conversation with a wonderful writer named John Bucchino. I was kind of whining to him about how stuck I was. And he simply said, “Oh, well, you’re just being the editor too soon.”

And I realized that when we do any kind of creative work, we’re constantly switching invisible hats. Sometimes we are the writer, who is just putting stuff out there without judgment. And sometimes we are the editor, who is evaluating what’s out there and making choices. If the editor shows up too soon, then you’re stuck, then you have writer’s block, because you just judge everything prematurely.

When to become the editor is an instinct. When you have enough raw material that you can begin to judge it, you can begin to assemble it, you can begin to make choices. But it’s so easy for that editor to show up too early.

Put the editor back into his or her little cubby until it’s time for him or her to show up.

What I have to do when I get stuck is get out of the way and just allow the writer to just do terrible work, if that’s what it takes at first.

It’s sort of like pump-priming out on the farm — where I never lived — where they’d have to get water from the well. They would just put the pump handle up and down and up and down and nothing would come out. And then kind of brown, horrible sludge would come out. But then eventually the water would come gushing out.

Imagine that this is the company of “Wicked” pointing the way to the door for your inner editor. Don’t ever let that editor in too early. Photo by Joan Marcus 2022

Chapter 8: How I start to write

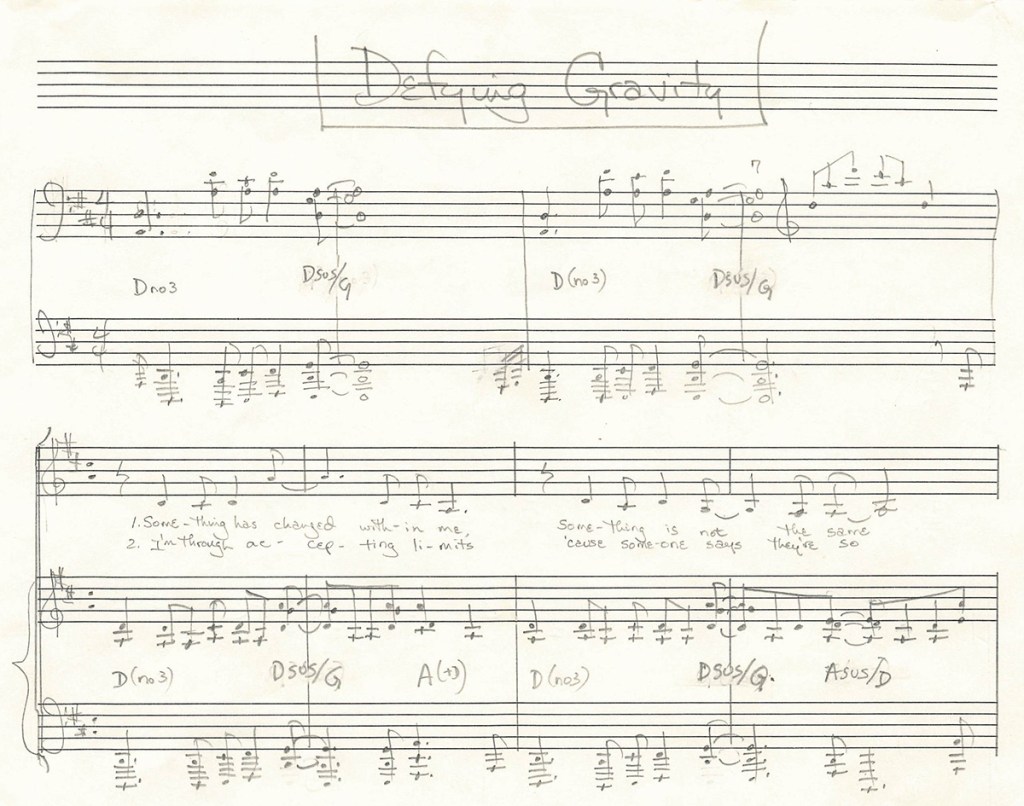

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: Long before I knew it was time actually to write songs, I started jotting down little fragments of melody, or chord patterns, and then I would just put them away. About a year and a half later, I went back to look at these little scraps of paper with shards of melody or chords. I discovered things like this: [piano plays]

I also had a melody that was like: [piano plays]. I think I also had that big jump. That’s all that was there.

From my very first outline: “At the end of the first act, she flies.”

Once Winnie had written script pages for it, the first thing I did was make a list of possible titles.

I always like to start with the title of the song, to define for myself how does that title embody a moment in the story. And I called Winnie. And I read her a list of six titles. One of the titles was “Defying Gravity.” And Winnie said, “I think I like that one.” And I said, “Good, because that’s my favorite.”

Once I had the title, and I kind of had this tune, I was able to write it really quite quickly. The song evolved over time, because in the show there’s a lot of action, and while the bits and pieces that came in and out of it between Elphaba and Glinda developed over time, the song itself never changed in terms of the music and lyrics. The only thing that changed was when we cast Idina Menzel as the Wicked Witch. When I was teaching her the song and I got to the last verse, which is when she flies, the original tune was the same tune as the first two verses. It was [singing] “So if you care to find me / look to the western sky.” And Idina said, “I’m flying at that point. Can I just stay up on a high note?” And I just said, “Well, you have to sing it eight times a week.” And she’s like, “Oh, that’s all right.” And so it turned into [singing] “So if you care to find me / look to the western sky.”

The original handwritten score for “Defying Gravity,” by Stephen Schwartz. Click through to see the full 8 pages at full size.

Chapter 9: The first reading

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: It was at a small theater called the Coronet Theatre, in a room in the basement with a little stage. We had actors that we knew read and sing through what existed of this score. We had about 12 or 13 friends come to see it, who we respected their taste, but also knew they would tell us the truth. And then we learned a lot.

The first act at that point was at least two hours long. It was way, way too long, as these things tend to be.

We learned that the audience brought with them the 1939 movie. They didn’t care if we changed anything from the L. Frank Baum stories. Many of them had read Gregory’s book, but they did not care whether or not we were faithful to that book. But we realized we could not do anything that directly contradicted the movie.

We can show what you don’t see. We can show what would’ve happened if they moved the camera to the right or kept it running after a scene happened. But from that point, it was like the movie was a documentary.

One of the people who came to that reading is the producer Jeffrey Seller, who ultimately produced Hamilton, and he said to me afterwards, “Anytime you are with the two girls, you are golden, and whenever you go away from them, you have trouble. So just be careful not to go away from them unless you absolutely have to, and when you do, don’t do it for too long.”

That’s when we learned that it was really the story of the two girls. It was their relationship that most spoke to people and was most vivid theatrically. That was going to be the key to the show.

As we developed the show, Winnie and I made a little sign. And every now and then as we went down various roads, one of us would hold up the sign that said, “It’s the girls, stupid.”

JUNE COHEN: Did you notice how specific Stephen is about WHO he needs at the show’s first reading? He needs people he trusts — and who he can trust to tell him the truth. Then once he finds that truth for the audience? He keeps himself honest about that: “It’s the girls, stupid.”

Brittney Johnson as Glinda, and Lindsay Pearce as Elphaba, are the beating heart of “Wicked.” Photo by Joan Marcus, 2022

Chapter 10: Writing the final song

How do you make sure your work rings true? Rhyme it with real life.

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: I often find, when I’m writing, it’s helpful for me to bounce ideas off of other people, or investigate an idea through personal stories. And of course I impose on my family all the time, because they are there and they have to humor me.

When it was time to write the final song for the two women, Elphaba and Glinda, who have been friends and enemies and everything in between, I knew that that song was the heart of the show. And if I didn’t get it right, the show wasn’t going to really work. Winnie had helped me arrive at the title, “For Good.”

My daughter, Jessica, happened to be visiting my house in Connecticut. She has a friend that she has known since they were about seven years old, Sarah. They have had a rather complicated relationship where there were times when they were very angry with one another, but ultimately forgave each other and really deep down love each other.

I went to her with a yellow pad and pencil at hand, and I said, “I want you to tell me: If you knew that you were only going to see Sarah one more time in your life, and then you would never see her again, what would you say to her?”

And Jess thought. And she started to say things about, “Well, I feel like the people who are important to you come into your life for a reason, and sometimes you don’t know what that is right away.” She said several things, which I wrote down and which more or less, with some rhymes thrown in, became the first verse of “For Good.” I’ve always thought that one of the reasons that song has as much impact as it seems to is that it’s true.

Chapter 11: It’s not working

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: We were trying out in San Francisco and things were enormously tense with a giant musical and a lot of it not working.

At an out-of-town tryout, your show’s not finished by definition. It’s a tryout. There’s going to be a lot wrong with it, and there are going to be things you’re going to learn and things you’re going to have to fix. But at the same time, people are judging you as if it is the final work. So it’s a very fraught experience.

The night after the third preview, Joe Mantello, our director, and I were at loggerheads. We had a meeting, it was at the Clift Hotel, and it was Marc and David, our producers, and Joe and Winnie and me. There was a lot of discussion about how to fix things that weren’t working, and it was a very tense meeting where angry words were spoken. Joe can be kind of a tough personality, and Winnie is very sensitive, and at one point Joe said something that made Winnie cry, which of course immediately made me, like, you charge in as the knight and defend my collaborator. I started yelling at Joe and it descended into a lot of angry exchanges. And finally, we just decided, “Well, we’re just not going to get anywhere at this meeting.”

I had a meeting at the theater around the corner, and I remember stalking angrily out of the Clift Hotel and turning the corner to go to the theater where Wicked was playing, and there was a huge crowd in front of the theater. And I thought, “Oh no, there’s been a terrible accident. A brick has fallen off the building and hit somebody or a car has gone haywire and driven into the theater. What is this mob doing there?”

And as I got to the theater, I realized that it was a line at the box office. After three previews of this show that no one had ever heard of when the show was still a mess, without a star in it, and people were lining up for tickets, I thought, “Oh, maybe we’re onto something here. Maybe we shouldn’t all be so angry at one another.” At least for me, from that moment, the process of collaboration was a much easier one.

This vintage video from the 2003 San Francisco tryout at the Curran Theatre shows the brilliant work behind the scenes that’s required to bring a show to stage.

Chapter 12: We create the iconic song “Defying Gravity”

How do you create one true vision from the work of many collaborators? Let each one build on the others.

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: When you are a young writer and you’re feeling terribly protective of your material — as I know I did — and you’re afraid you’re going to lose what’s really valuable to you about it. That is a very uncomfortable and scary process. Over time, I have come to realize that you want gestalt to be in effect. You never know where the best idea is going to come from. The whole is going to be better than any one thing that anybody, including you by yourself, could have brought to it.

There are three moments in “Defying Gravity” that are close to my heart:

The first time you hear this [piano plays], it’s very sort of slow and just comes up underneath it, as Elphaba is realizing that she is powerful.

The moment that Joe Mantello essentially created when the witch stands up and she’s suddenly revealed as the Wicked Witch of the West.

And then the great moment for me is the moment where she flies. Yes, I brought the song, but the way Joe staged it and the way it is lit — I think Ken Posner’s lighting for “Defying Gravity” is the best lighting I have ever seen in the musical theater. And the idea for the costume that Susan Hilferty came up with. It’s like all these really talented theater artists absolutely firing at their full-cylinder ability, and all of it comes together. And I just feel, well, that made for a really thrilling moment in the theater, but it required the full collaboration to deliver it.

Lighting by Ken Posner, costumes by Susan Hilferty, and staging under the direction of Joe Mantello bring to life the soaring moment in “Defying Gravity” when Elphaba realizes she is powerful. Image of Kara Lindsay, Rachel Tucker, and the cast of “Wicked.” Photo by Joan Marcus

Chapter 13: Opening night

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: I cannot give you stories about opening night on Broadway, because I do not go to opening night. I haven’t gone to an opening of my show since 1974. I just find the whole experience just too difficult emotionally in many ways. First of all, you’re feeling extremely vulnerable. Secondly, there are all these strangers there and you go to this party afterwards and people you’ve never seen before are elbowing you out of the way to get to the food. And then, everybody is waiting to hear word about what the reviews are, and it’s so barbaric. I just learned many, many years ago: Just don’t be there.

And so, my wife and I went to Vermont. In the morning my wife, Carol, went out and got the reviews. I just wanted to know like, well: How did we do? I find out The Times didn’t like it, but this person did like it. And then you start to get a feeling like: Are we going to be okay or not?

Understanding that Wicked had found its audience grew over time, over the first three months of the run. It was clear that we were getting pretty strong response. I began to know that we had a really good chance of being successful. What there was no way to know was that it would become a phenomenon.

Chapter 14: The truth was in you all along

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: I’ve spent a lot of time trying to figure out why it has become such a phenomenon. Why it speaks so deeply and so intensely to people. That character, the Wicked Witch of the West, the green girl — as David Stone, our producer, says: All of us have that green girl inside us. And obviously in many ways, I have nothing in common with the character of the Wicked Witch of the West. But we all feel we’re misunderstood. We all want to be loved and valued, but not at the cost of losing ourselves and our souls.

And then the other thing is the relationship between the two women, the depth of that unlikely friendship. Whether you are two women or two men, pretty much everybody has one of those in his or her life. So that also spoke to people.

I’m not someone who really believes that the arts change the world, because if they did, we wouldn’t be living in the world we’re living in. We’d be living in a much better world. So clearly they don’t have that much impact. But I do have anecdotal evidence of an individual work being able to change an individual life, and Wicked has done that for a lot of people. That’s what is so wonderful and mysterious to me about how art communicates. That some kind of human truth way down deep is universal and common to us as a species. And if we just have the courage to tell our truth, it will speak to other people.

JUNE COHEN: I want to thank Stephen for sharing his story with us. And I want to thank each of you for listening. I hope something in it inspires universal truths in your own creative work.

It might be the way Stephen championed the green girl we all have inside us. Or the way he turned to his daughter to discover a universal truth about friendship. Or maybe it’s his unforgettable mantra: “Tell the truth, and make it rhyme.” And the world will sing along.